Barrier-free access to higher education is urgently needed in Canada. In 1988, 12 per cent of university revenue came from students’ pockets via tuition fees. Fast forward some two decades later and by 2012, 41 per cent of university revenue was generated by tuition fees.

That’s an average 1.2 per cent increase in tuition fees per year. At this rate, tuition fees will cover 100 per cent of university costs by 2061. Or even faster when you consider that in 2010, the University of Toronto became the first public university to receive more funding through tuition fees than government grants.

“Since the 1990s, there have been massive cuts to the Canada Social Transfer,” explains Jessica McCormick, National Chairperson from the Canadian Federation of Students (CFS). “Post-secondary education institutions had less funding and thus increased tuition fees as a response.”

The results are unsurprising. Students have become dependent on loans, culminating in high levels of debt. When you consider the stressful impact of rising student debts coupled with the current economic context, you have what some researchers are calling generation squeeze.

Students are bearing the financial burden of a system whose cost should be spread over the entire population, just like health care. Imagine if only the sick or the elderly paid for Medicare since they use it most, by a fee-based system akin to tuition fees. That would be grossly unfair, wouldn’t it? And yet, that’s exactly what we’re doing to students in the case of higher education.

Public vs. private education

“[In the last 30 years,] we have seen this shift in narrative over who benefits for education,” says McCormick. “It’s being looked at as an individual benefit instead of a national social benefit for all of society. When people are able to go to university and get a good job, then they are able to pay for the next generation of people who go. That way everyone uses and contributes back to the system. As it stands now, a low-income person pays the same tuition fees as a high-income person. They have to get a loan, then pay back the loan with interest, so in the end low income people pay more for their education.”

If the trend continues, then Canada will end up privatizing a fundamental public right, shying away from an equitable European model that values free higher education, and moving toward the American model where universities are inaccessible to low income students.

Over 30 countries around the world have fully public post-secondary education, including Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Iran, Sweden and Morocco.

“In Germany, they had no tuition fees for a long period of time and had introduced it back and are now [eradicating them] again,” says McCormick. “It’s taboo to bring up the idea of free post-secondary education [in Canada.] I think that a lot of the resistance to reducing tuition fees and giving free tuition [comes from the fact that] the federal government is firmly entrenched in an ideological issue. Students feel it’s a matter of priorities.”

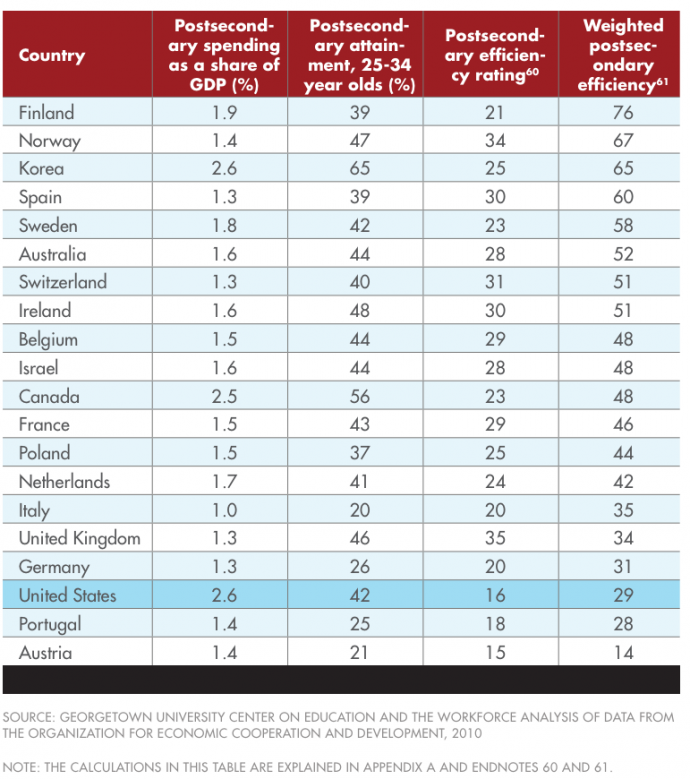

The irony is that Canada spends more on higher education, 2.5 per cent,as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), than most of the European countries cited above, including Germany at 1.3 per cent.

Surely, Canada, one of the richest countries in the world — yet the only OECD country that doesn’t have a department of Education at a federal level — can do better? When did the idea of free post-secondary education become a radical one?

The only other country that spends more is the U.S. According to a new report though, unlike our American counterparts, our education model isn’t completely inefficient, but the reality is we invest a lot for a mediocre return.

Are university degrees meaningless?

Kent Kuran frames the situation from an interesting angle: the fact that Bachelor degrees are quickly becoming the equivalent of high school diplomas.

This kind of “credential inflation,” as Kuran puts it, once forced upper-class collegiate institutes and lower-class highs schools to merge into the secondary schools we know today; the same thing is happening to colleges who are being pushed to merge with universities by offering joint degrees that prepare students for jobs.

“In other words, university is the new secondary school — another level of general education soon to be the bare minimum for employability,” writes Kuran. He imagines every suburb will have one, just like it currently has a high school. A very realistic prediction.

But whether colleges or universities merge, the fact remains that most of today’s students require a university degree to get a decent-paying job, while at the same time paying more than any other Canadian generation for post-secondary education. Provincial case studies demonstrate that this may ultimately be a question of political will and priority.

In Newfoundland and Labrador, both liberal and conservative provincial governments have made it a priority to reduce tuition fees. “They wanted people to stay in the province,” says McCormick. “It was a retention strategy and an attraction strategy to bring in more students from other parts of Canada. And they have had successes: tuition fees in that province have been frozen for the last 13 years and they have the lowest tuition fees in the country [as well as] a generous grants program.”

The CFS states the most effective way to create an affordable and high quality post-secondary education system is through “a federal act that would enshrine Canada-wide standards and define the requirements of transfer payments. An act would tie funding to a commitment from the provinces to uphold a set of principles, namely public administration, affordability, comprehensiveness, collegial governance and academic freedom. In return, provincial governments would receive increased and predictable funding from the federal government.”

The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives studies find that lowering tuition fees is not only possible, but that it’s a more democratic and fairer choice. And, as demonstrated by the Quebec student strikes, students want fair and equal access to education.

So, as Nelson Mandela rightfully said, “It seems impossible until it’s done.” So let’s get it done.

Sanita Fejzic is an Ottawa-based literary author and freelance writer. She freelances for a number of newspapers, magazines and blogs including rabble.ca, The Ottawa Magazine and Apt 613. She was also the author of “The Beaver Tales” blog for Xtra newspaper as well as the Ottawa correspondent for 2B, Être and Entre Elles magazines. Sanita’s first novella, To Be Matthew Moore, was shortlisted for the 2014 Ken Klonsky Contest, and she has published her poetry and short stories in various literary magazines including The Continuist, Guerilla, Byword and The Newer York.

Photo: flickr/Glenn Euloth