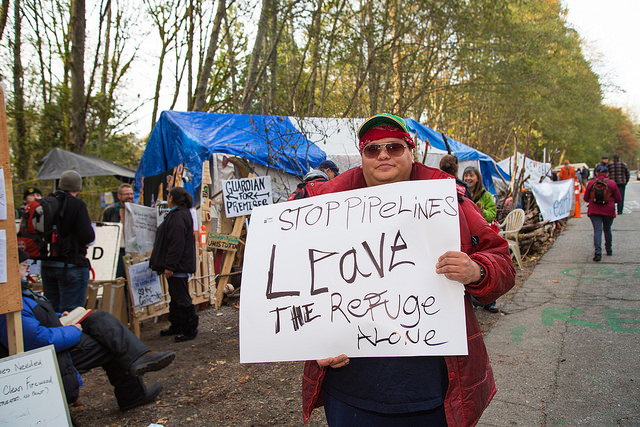

Burnaby Mountain, probably best known as the home of Simon Fraser University, is the site of a proposed expansion of Trans Mountain, Kinder Morgan’s Edmonton to Vancouver tar sands pipeline. The mountain is also unceded Indigenous territory, part of the traditional land of the Musqueum, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations. But for the last few months, Burnaby Mountain played host to a concerted struggle for climate justice and Indigenous sovereignty, a battle over one pipeline that became a proxy fight over the Harper government’s fixation with extractive industry as a whole.

As organizing against Kinder Morgan’s exploratory work built, the Texas-based energy infrastructure giant enlisted the B.C. courts in an effort to salvage its pending National Energy Board (NEB) application to expand Trans Mountain.

In late October, Kinder Morgan filed a multi-million-dollar lawsuit against five named pipeline opponents, the community organization BROKE (Burnaby Residents Opposing Kinder Morgan), as well as John and Jane Doe and persons unknown. The company sought damages — for nuisance, assault by threat, trespass, intimidation, and interference with contractual obligations — costs, and most crucially, an injunction.

Injunctions ––court orders prohibiting certain actions or behaviour — are commonplace in B.C., an all-too typical response by corporations — and sometimes the government — to disputes over land, resources, and most recently, extractive projects. Kinder Morgan was no doubt expecting smooth sailing, on the mountain and in the courtroom.

Their injunction aimed to keep protesters away from two drilling sites on Burnaby Mountain, key “bore holes” central to gathering the necessary evidence for Kinder Morgan’s NEB application, due December 1. The case was first brought before B.C. Supreme Court Associate Chief Justice Cullen on one day’s notice to the defendants.

He granted an adjournment so the defendants could find lawyers, and then, after hearing the three-day long application, surprised everyone by reserving his judgment for up to 10 days. He turned out to need less time, and issued a judgment on Friday, November 14 that granted Kinder Morgan an injunction preventing access to the bore hole sites and preventing interference with Kinder Morgan’s “works” and access.

The ruling delayed enforcement of the injunction until 4 p.m. the following Monday, it was Thursday, November 20 when the RCMP began making arrests. Twenty-four people were arrested that first day, all of them charged, not with a criminal offence or even trespass, but civil contempt of court. Most were released on the spot after signing a promise to appear to appear in court in January, 2015, and in some cases, an additional undertaking to not violate the injunction again.

Three people — two of them Aboriginal, the third a tree-sitter pulled from his perch by the RCMP — were held overnight until a hearing before B.C. Supreme Court Chief Justice Hinkson. The hearing, held in downtown Vancouver’s cavernous Air India courtroom, was an odd affair quite unlike most bail hearings. The activists, represented by pro bono counsel (including myself), faced off not against Crown Attorneys but Kinder Morgan’s own lawyers, joined by counsel for the RCMP. C.J. Hinkson released all three protesters on a simple promise to appear with no conditions. It was the first of several micro victories to come.

The number of protesters on the mountain continued to grow, as did the number of arrests, a wave of civil disobedience that quickly drew comparisons to the mass arrests of the 1994 Clayoquot Sound campaign.

On November 24, Kinder Morgan filed an application to extend its injunction by 11 days, to December 12, expand its reach, and, more surprisingly, “to clarify the precise GPS coordinates” of the injunction boundaries “[f]or the certainty of the RCMP and protesters.”

On Thursday, November 27, as UBCIC Grand Chief Stewart Phillip and Tsleil-Waututh elder Amy George were arrested crossing the injunction line, ACJ Cullen ruled on Kinder Morgan’s application, refusing to extend the injunction or expand its “exclusion zone.”

If these denials had seemed impossible just 24 hours earlier (until a Kinder Morgan VP’s letter to the NEB indicating that the company did indeed have the geotechnical information it needed already was disclosed in court), the remainder of the judge’s decision was even more stunning. ACJ Cullen granted Kinder Morgan’s application to “correct” the GPS coordinates, thus setting the stage for the withdrawal of contempt of court charges issued the previous week.

It felt like a victory and it was, especially as Kinder Morgan’s trucks began rolling off Burnaby Mountain that same afternoon. And for the 112 people arrested for crossing what turned out to be an inaccurate injunction line, ACJ Cullen’s invitation to Kinder Morgan to vacate all Promises to Appear and Undertakings it meant that the threat of looming contempt trials — not to mention possible fines and/or jail terms — was suddenly lifted. But a week later, the wages of victory are harder to grasp.

Most clearly, the expanded Trans Mountain pipeline remains under consideration by the NEB, an approval process now “streamlined” after changes to the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act in 2012 removed the requirement of a Joint Review Panel, leaving the decision solely in the hands of the NEB panel.

For the City of Burnaby, itself a pipeline opponent, ACJ Cullen’s decision served only as a distraction from the municipality’s jurisdictional lawsuit against the NEB and Kinder Morgan (in which Burnaby was denied an injunction pending trial).

In the meantime, the RCMP had run up costs estimated at $1 million while enforcing the injunction, a bill that so far appears to be Burnaby’s to pay.

Yet the cost of policing Kinder Morgan’s injunction is not just a fiscal concern for Burnaby taxpayers, it is also the clearest example of the perverse use of private-public partnership injunctions and contempt as tools for managing public opposition.

The resort to injunctions by extractive industries embroils the courts and police in the enforcement of struggles that — despite all appearances to the contrary — are constructed by the law as private disputes. That the NEB loomed large behind the opposition to Trans Mountain serves only to highlight the broader absurdity of injunctions founded on tenuous civil suits, and yet enforceable against all, as a means of policing public dissent and facilitating opposition to environmental injustice.

In the aftermath of the battle for Burnaby Mountain, understanding this contradiction puts a legal victory in context, and seizing on it provides one tool for building stronger, more resilient movements for climate justice in the years to come. Injunctions, contempt and the policing of public protest point us toward broader questions of environmental governance, policy-making and most importantly, power, paving the way for prying political victories out of a dense web of law.

Irina Ceric is a progressive lawyer, activist and legal scholar. A recent transplant to Vancouver/Unceded Coast Salish Territories, she practices immigration and criminal law with Edelmann and Company. Formerly based in Toronto, Irina was a founding member of the Movement Defence Committee, a law teacher at York and Ryerson Universities, and a longtime community activist.