Classes remain cancelled at Ontario’s 24 publicly funded colleges.

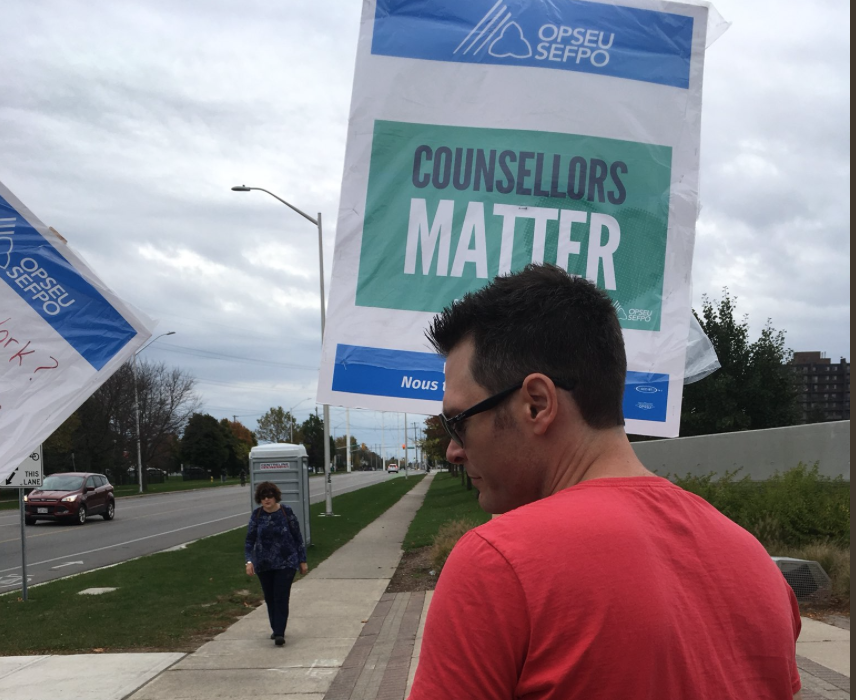

More than 12,000 professors, instructors, counsellors and librarians took to the picket lines on October 16, after the Ontario Public Service Employees’ Union (OPSEU) and the College Employer Council failed to reach a new agreement.

The two sides were in negotiations throughout the summer.

The union presented its final offer to the council on October 14. Council rejected it.

Bargaining is not happening currently, and the province’s minister of labour has appointed a mediator.

The union’s offer included more protections around academic freedom, and sought to reduce the number of non-full-time faculty. It proposed colleges come to a 50-50 ratio of full-time to non-full-time positions by the time the agreement ends. It also strengthened job protection for partial-load instructors, those who teach between six and 12 hours a week. The union’s offer includes a guarantee that these instructors be given at least three weeks’ notice if their contracts are being renewed. It gives first right-of-refusal on new teaching assignments to partial-load instructors whose contracts end before the assignment begins or have ended within the previous six months.

In the old contract, only partial-load instructors who had taught the courses before, or had been a partial-load employee for at least eight months throughout the last four academic years, had right of first refusal.

The union also wants a wage increase of 9 per cent over three years; the council a 7.75 per cent increase over four years.

“If it had been about our wages and benefits, this would have been settled in July,” chair of the bargaining unit, J.P. Hornick, told picketers gathered outside George Brown College’s King Street East campus in Toronto on October 17.

In a statement issued by the council on October 15, Sonia Del Missier, vice president of academics at Cambrian College in Sudbury, called the strike “completely unnecessary and unfair” to students. The statement says changing staffing ratios will eliminate thousands of jobs and reduce program flexibility. These changes, along with increased salaries, will cost more than $250 million a year, she added.

But the current college system leaves instructors without the resources they need to best serve students, especially international students or those who need accommodations to learn, Hornick, a labour studies professor at George Brown, said on October 17. Colleges need to spend more to support faculty — not on buildings or administrators’ salaries, she said.

Picketers were enthusiastic, marching with pets and children. Others banged drums and played ukuleles, singing songs and chanting. “We’ll never be defeated,” they sang. “The workers are united.”

Some full-time faculty on the line began their careers working on contracts, and recalled the financial strain and anxiety this caused.

Ola Rahatka has taught English as a second language on a full-time basis for five years at the college. Before that, when she only had contracts, she would be nervous about affording a day off when she was sick. The pressure of always looking for work could start to affect someone’s work ethic, she said, adding: “I want people to focus on the quality of their work, rather than securing the next contract.”

Rahatka said she understands strikes like this are frustrating for many people. But if workers don’t stand up for their rights they become more vulnerable.

Fran Odette said she’s picketing for the students. “I don’t want to be here,” she said. “I’m on the line because I want (their) experience of learning to be the best that it can be.”

Odette is a partial-load instructor in the assaulted women and children’s counsellor/advocate program. She also teaches a course on disability issues. Students who have personally experienced these topics often come to speak with her as they process what they’re learning. She’s not a counsellor, but those can be sensitive conversations.

But Odette said one of the greatest challenges of her job is not knowing if she’ll have another one. The most notice she’s received about a contract being renewed is three weeks — a period of time that’s too short, in her opinion.

Many students want to return to class, too. Some are studying for deferred exams; others are working on assignments.

Some professors talked to students about the possibility of the strike, and explained some of the reasons for it.

“I’d probably be on strike, too,” said Lavanya Saharya, a second-year civil engineering technology student, who said she wants the strike to end as soon as possible.

Jerry Lemay, a first-year business administration student, said he’s worried about losing courses and having to pay for them again. He needs an average of 85 per cent to graduate, he said, and math concepts are better learned in-class than on his own.

He said teachers need good benefits, but their disputes shouldn’t negatively impact students.

“Students are essentially the future leaders of the world,” he said, adding that it’s not fair to students if the strike takes away their ability to learn.

No college strike in Ontario has ever lasted more than three weeks, but Hornick told the crowd she thinks it’s unlikely the government will force faculty back to work.

Politicians are urging the government to do what it can to ensure both sides return to bargaining. During Question Period this week, Ontario’s official opposition leader, Progressive Conservative Patrick Brown, urged Premier Kathleen Wynne to encourage sides to renew talks.

In response, Wynne said in the legislature on October 17 that the government will do “everything we can to get everyone back to the table,” saying strikes like this are “always an uncomfortable situation for everyone, and a distressing situation when people are not able to go to their classes.”

The strike comes as the government considers changing the Employment Standards Act and the Labour Relations Act. Bill 148, The Fair Workplaces and Better Jobs Act, passed second reading on October 18. It still needs to pass third and final reading. If passed, it would ensure equal pay for part-time, temporary, casual and seasonal employees who do the same work as full-time employees.

OPSEU’s final offer to the colleges council includes that the two parties will meet to negotiate changes based on Bill 148 within 30 days of it passing, if it does. If agreements can’t be reached within a year, either party can ask for help from an outside arbitration board.

OPSEU has also been organizing part-time and sessional college faculty. Part-time faculty are those who work less than six hours a week. Sessional instructors cover leaves, like paternal leaves, or work more than 12 hours a week. Their vote to join the union was held October 13. Hornick said on October 17 the votes are still being counted.

Meagan Gillmore is rabble.ca‘s labour reporter.

Photo: Erin E. MacDonald/Twitter

Like this article? Please chip in to keep stories like these coming.