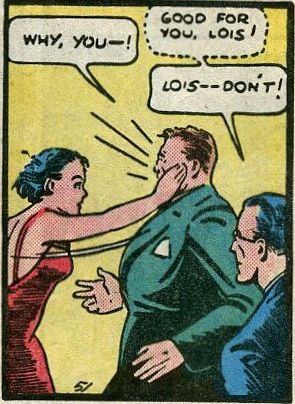

I went to my first political convention last weekend. The NDP Leadership Convention, to be exact. I felt a bit like an imposter: I didn’t wear a partisan t-shirt or wave a sign. Instead, I scribbled in my little notebook, took loads of photos and eavesdropped incessantly. I could have been Lois Lane.

I had been offered blogger’s media accreditation through my friends at rabble.ca. I jumped at the opportunity to do some academic research on affect.

I’m very interested in the ways technology and affect work together to create embodied national feelings — feeling with a sense of touch. In a previous post, I wrote about Jack Layton’s death and funeral and the contagious affects that surrounded that moment. Despite Layton’s call to “change the world,” I wondered at the time if this particular kind of collective, contagious affect that circulates around public figures is antithetical to grassroots organizing.

I walked into the halfway point of candidates’ speeches. “I like how clean it is,” said one conventioneer, referring to the collegial behaviour of the candidates. I was struck by how scripted the entire event was. Thomas Mulcair walked through the hall like a king, with a marching band leading the way. Among all the screens was a giant teleprompter, so you could read along to every single word being said. The only unscripted moment I witnessed was when candidate Peggy Nash’s script was speeded-up (she had taken up too much time), so she ad-libbed without missing a beat. For some reason, she defaulted to lgbt rights — it wasn’t in her script but I didn’t mind. It was the only reference to lgbt anything that I heard the whole time I was there.

In the evening I attended the tribute to Jack Layton. More scripted speechifying, and a succession of straight white men lauding Jack in the video tribute. But I could feel the waves of feeling rolling through the all-ages audience, especially during an upbeat speech by Olivia Chow. The screens were given over to panning shots of the City Hall chalk memorial, that rich Babylon of citizens’ voices, reminding me what the affects of activism could be, and contrasting with the exceedingly conventional affects at this convention.

As the convention dragged to its seemingly inevitable conclusion — the election of centrist Thomas Mulcair as leader, I attended a party comprised mostly of queer women NDP-ers, several of whom had been to the convention. I spoke with my filmmaker colleague Gerry Rogers, currently provincial MP for St John’s Centre, and the first openly queer politican elected to Newfoundland and Labrador House of Assembly.

At the convention, when the race narrowed down to three leading male candidates, Gerri had helped to convene a meeting of a women’s caucus. The caucus invited each candidate to speak to them, querying them on their positions on choice, among other things. They were then able to announce to national media that all of the candidates, including Mulcair, had declared a pro-choice position. That was one of the smartest moves I’d seen all weekend.

The women at the party were veterans of savvy feminist political organizing. The mood was muted (though the drinking was not!). Disappointment in Mulcair’s ascendance was palpable. But there was joy and pleasure and high humour, too, and that was certainly contagious. It reminded me of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s notion of ethical possibility, which, she argued, “. . . is founded on and coextensive with the subject’s movement toward what Foucault calls ‘care of the self,’ the often very fragile concern to provide the self with pleasure and nourishment in an environment that is perceived as not particularly offering them.”

To produce ethical possibilities, long-term progressive political organizing requires a circuit of affects. A one-note tune of positivity seems merely to be the melody of the status quo. The recent Ontario and federal budgets and their brutal attacks on poor people, seniors and youth will demand much, much more than that.