Not‑for‑profit corporations aren’t new. Neither are many of the laws that govern them. Like us, laws age and have tendency to become outdated.

Long ago, we decided we should live by the rule of law. Our predecessors adopted the practice of writing down these laws so we might all know what they are. The result is a wonderfully complex mess requiring an industry – lawyering – to interpret them.

Try as we might, the law as written isn’t always right. Of course, there’s usually little one can do to change the law, other than voting a couple times per decade. Remember! If your elected representative doesn’t make your desired change, just sit tight for a handful of years and get ’em next time.

Let’s file “disaffected voter” under “it is what it is.” The system’s not perfect, right? It rewards some, deprives others. It is what it is.

Fortunately, our predecessors also realized “for‑profit” corporations, and the governments that enable and (to some extent) regulate them, don’t adequately provide for those who pay the most for “the greater good.” Yes, the Canadian social contract includes universal basic health care, but inequality persists – not because we can’t solve it, rather, because it’s fundamental to the whole deal.

That none are equal underlies the competition of all‑against‑all. Some are better than others, so the theory goes. Rich or poor, you get what you deserve. Sound preposterous? It’s certainly an oversimplification. A shortcut to an unoriginal conclusion: we’re not all rich, or well‑fed, or housed, or…well, you get it. If you still can’t see “those less fortunate” around you, it’s by choice.

Many see the suffering of others and try to help. At least some 59,000 times in Ontario alone, people have banded together to deliver a benefit to the public. It’s the same everywhere the law allows incorporation without the intention of profit. And so, not‑for profit corporations have come to play an important role in modern times.

You might think of not‑for‑profits as proof of humanity’s co-operative instincts. You might see them as self‑defeating entities necessitated by a system of unjustly distributed privileges, actively plugging every hole, and in so doing, keeping that very system afloat. Or, you might find comfort in knowing there’s a not‑for‑profit out there that affords you the opportunity to give back and help those who (unlike you, you fine specimen) lost their personal slap‑fight with the invisible hand of the market.

No matter your take, shouldn’t you support not‑for‑profits? Shouldn’t we vote for law‑makers who will make it easier for not‑for profits to operate?

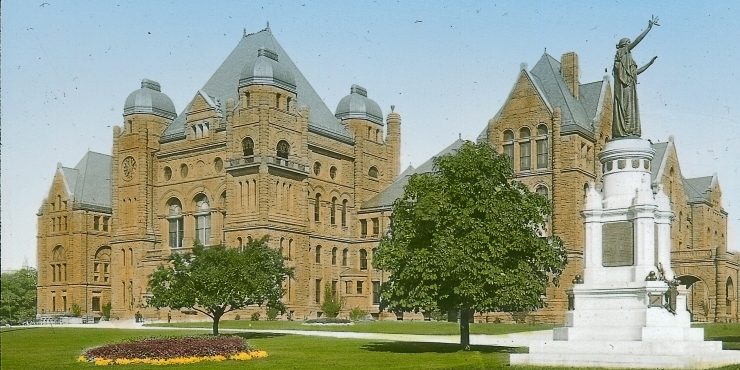

Ontario’s Not‑for‑Profit Corporations Act, 2010 (the “ONCA”) was recently proclaimed into force… eleven years after it became law. ONCA promises to make it easier to govern not‑for‑profit corporations. Much digital ink has been spilled on the subject of “next steps” for affected entities, which could be as many 59,000 corporations. Many of our clients are among them. We are increasingly being asked to perform corporate reviews. It’s easy to see why.

ONCA provides a three‑year transition period. Any not‑for‑profit corporation that doesn’t bring itself into compliance with the ONCA by the end of that transition period could end up in a real mess, legally speaking.

Much has already been written on this. Not so for why it took ONCA so long to be proclaimed into force. ONCA replaces Ontario’s Corporations Act, which dates to 1907. According to the province, ONCA provides “a modern legal framework to meet the needs of today’s not-for-profit sector.” Yet, it sat idle for so long it was amended three times before it was even in force (by the Forfeited Corporate Property Act, 2015; in 2016, to resolve differences between French and English versions; and by the Cutting Unnecessary Red Tape Act, 2017).

Those awaiting its proclamation into force may have wondered if it would ever arrive. For some, converting to a federal corporation under the Canada Not-for-Profit Corporations Act (the “CNCA”) was the better way to go. Like Ontario, the feds refer to their latest not‑for‑profit laws as “a modern framework.” And, its history is similarly maligned. The Companies Act was amended in 1917 to include not‑for‑profit corporations for the first time. For more than 80 years, the provisions for not‑for‑profits saw no substantial change. In the early 1970s, the federal government started working on a federal not-for-profit statute. Says Corporations Canada, “Seven bills were introduced in Parliament and died on the Order Paper until the 8th attempt finally made its way through the parliamentary process and came into force on October 17, 2011.”

A recap: By the 1970s, the feds acknowledged that its 1917 law needed an update. Some forty years later, it updated that law. Not to be outdone, in 2010, Ontario enacted a law to replace a statute dating back to 1907, then let it languish for 11 years before proclaiming it in force.

What’s the take‑away?

First, we find here a relatively mundane example of the imperfections inherent our system of writing down the law. The law‑as‑written isn’t the actual set of rules by which we ought to govern ourselves. It’s necessarily incomplete. Always will be.

We could sensationalize this. More dramatic than corporate governance? How about a hero who must choose between their conscience and the law? Like, a draft dodger conscientious objector.

That’s not this. The enactment of the ONCA and the CNCA is a tale of incremental improvement to bureaucratic efficiency.

Which leads to a final thought. Even without the benefit of modernized laws, there are a whole lot of not‑for‑profit corporations. We could take this as an indication of just how much the business of taking care of each other has been left to the private sector, or, as a measure of how much deprivation is really out there, but let’s finish with something a little more uplifting. No matter how inconvenient, how antiquated, how incomprehensible the laws‑as‑written, when it comes to caring for each other, people will continue to join together to help those in need, without regard for how easy dotting the i’s or crossing the t’s might be.