Last month, a broad alliance of organizations from across the progressive spectrum came together to train 100,000 people in non-violent direct action in the hopes of supporting a wave of action targeting corporations and the politicians that own them. It was called 99% Spring. Some also called it “co-optation.” We call it “alliance building.”

The conversation within the movement has been fascinating, and reveals some key pitfalls that the resurgent U.S. Left might fall into if we’re not careful.

Grassroots groups that organize primarily in working class and communities of color such as National Peoples Action and the National Domestic Workers Alliance helped lead the 99% Spring process. Despite this, the terms of the debate have almost exclusively centered on the participation and limits of MoveOn.org (as a symbol and stand-in for more moderate liberals, the institutional left, and the nonprofit industrial complex). “Are the liberals co-opting Occupy?” or “Is Occupy co-opting the liberals?” There is indeed a historical precedent of radical peoples’ movements becoming de-fanged by the status quo. And yet, too often, the historic limits of the Left in the United States have been connected to its internal tendency towards sectarianism and the politics of purity. At this moment, our own circular firing squads may be a deeper threat to the viability of our movements than “outside” groups.

It is precisely because of our long-term work with radical grassroots movements that both of us dove into helping organize 99% Spring. We were each involved in writing the curriculum and designing the trainings. We were challenged by, and learned a lot from, the process. Our organizations (the National Domestic Workers Alliance and the Ruckus Society) are both movement groups that support frontline communities speaking and acting for themselves, and we were both part of the left wing of the 99% Spring alliance.

We are living in an incredible time. Occupy has helped us all re-imagine political vision and strategy. 99% Spring was a bold effort with a lot of success, real limitations, and some mistakes. We want to share our experiences from the heart of 99% Spring project to help our movements think more clearly about alliances, and some of the challenges that our political moment presents us.

At a crossroads

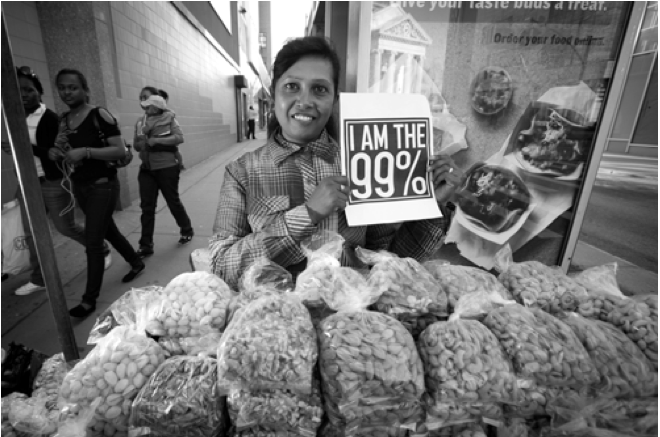

We are at a crossroads as a movement. Many have been slogging away in the trenches for years, pushing against the political winds and doing the slow work of organizing to build popular power within communities hit hardest by the economic and ecological crises. It was hard work, and it moved slowly. Last fall, Occupy exploded on the scene and challenged many of our assumptions about what was possible. By offering both an inspiring political tactic (“occupy”) and a unifying frame (“We are the 99%”), the Occupy movement was able to tap into the mass anger about the crisis that had been brewing for years. Occupy showed that it was possible to have an explicitly radical message, to engage in confrontational action and still speak to millions of people in this country. It became acceptable to talk about economic inequality, corporate greed and capitalism, and that changed the context for all of our work in important ways. It was a humbling moment for many long-term organizers. It also helped reveal some of the shortcomings of the institutional left.

But now what? Like all movements, we have lots of challenges. Most physical occupations have been evicted by the police, removing the public spaces that made us visible, and the ongoing police confrontations aren’t tapping into organic mass anger in the same way. This makes it difficult to do the big-picture strategic thinking we need to envision the next steps. This offers us all a moment of experimentation and innovation. In order to engage it, we need to seriously reflect on our circumstance.

Our friend Matt Smucker with Beyond the Choir puts it this way in “A Practical Guide to Co-option“:

Remember that Occupy Wall Street kicked off with a well timed call-to-action, a ripe target, some planning, and a lot of crazy luck. As a result, OWS has understandably had more of a culture of mobilizing than of organizing. It’s been a little like a group of folks who don’t know about farming who arrive at a farm at harvest time. There’s delicious food everywhere, and all they have to do is pick, pluck, and gather it. And eat it! “Wow,” one of them exclaims, “farming is awesome! Why would we waste our time cultivating the soil? This food is delicious! I want to eat it all the time! This is working very well. We should just keep doing this — all the time!”

Many have put a tremendous amount of work into ‘cultivating soil’ through the patient process of building working groups, general assemblies, and the mechanics of direct-democracy — especially in New York. We really respect this work. Yet still the tone and attitude of our movement in many parts of the country still relies on the “harvest” mentality. When we focus on the harvest without planting more seeds, we suddenly feel in competition with one another for the remaining food. This understandably leads to antagonism to anyone else eating at the table who we perceive to be politically different from ourselves.

But centering the conversation on whether or not liberals are co-opting radicals can promote an ideology: an unspoken belief that “the masses” are ready for revolution, if it weren’t for these misleading moderate organizations getting in the way. While its true that our organizing can be undercut by those who do not share our objectives (both of us have experienced this tremendous frustration), it is deeply out of touch to imagine that moderate groups are therefore our main enemy. Our enemy is existing power structures promoted by the 1% and elites in both political parties who prop them up.

Sectarianism distracts our movement from the real key questions that we need to grapple with:

– What are the potentials and the pitfalls of this political moment, and what has changed since last fall?

– How do we continue to connect with the millions of people who were touched by the movement last fall, and how do we continue to grow that base?

– What is it ultimately going to take to win in this country of hundreds of millions of people who agree that our society isn’t working, but have wildly divergent ideas about what the problems (and solutions) are?

Building broad alliances is a crucial part of answering these strategy questions.

What is co-optation anyway?

We don’t see many concerned about formal co-optation: that is, the concern isn’t that 99% Spring was trying to take over the actual operations of the Occupy movement or to buy off some section of its (non)leadership. Instead the concern is that moderate forces will take up the “99%” frame and adopt some of the direct action methodologies that galvanized mass support at the end of last year. The resulting fear is that they will then take the steam out of the mass support for the direct action taken by the more radical edges of the movement by providing a more acceptable outlet for the organic anger that Occupy was able to tap into in the past.

This is a reasonable concern that has received an unreasonable amount of attention.

Who was 99% Spring? What was the relationship building potential?

Involvement of communities of color.

The first mistake of the co-optation debate is its near-exclusive focus on MoveOn’s participation in the alliance. It’s true that MoveOn has been clearly involved from the beginning, along with other groups who have not traditionally used mass direct action as a tool for systemic change. It’s also true that 99% Spring would not have happened without the leadership of National Peoples Action, the National Domestic Workers Alliance, Jobs with Justice, and others who serve low income communities and communities of color. Training hosts included participation from UNITY alliance members Grassroots Global Justice, Right to the City Alliance, and more. They represent immigrant workers and other low-wage workers, African American communities, foreclosed homeowners and tenants, people on welfare and public housing residents. Many in the Occupy movement have reflected on the need to make sure that its mass public action needs to be connected to these communities, not just for the purposes of “diversity” but to anchor struggles within communities that are on the frontlines of our economic, political, and ecological crises.

The “left wing” of 99% Spring.

These organizations are not ‘moderate’ and should not be dismissed because they are non-profits; these are grassroots organizations which share Occupy’s transformative political visions. A serious debate about the value of a project like 99% Spring would not be focused exclusively by the MoveOn “elephant in the room;” it would have talked genuinely about the breadth of this coalition and the political concerns that it aimed to elevate – going after a range of power structures in the 1% that have kept many in our society locked out of the mainstream.

Positioning 99% Spring as an NGO watered-down version of Occupy yields a conclusion that the movement has nothing to learn from the project. The resulting abstentionism meant the movement lost this opportunity to learn about the dynamics of forming coalitions and to build in-person relationships with the working class and people of color base of many convening groups through the 99% Spring process. Alliances like these are full of contradictions, but we need to approach those contradictions as exciting challenges to be navigated rather than as problems to be avoided.

Was the intent of 99% Spring to co-opt?

Our movements cannot afford the arrogance of judging an entire alliance on the most (perceived) politically disagreeable actions of a couple members. The logic of the “MoveOn front group” argument is that because MoveOn’s web tools were used, and that they often engage in partisan electoral work, they are secretly the puppet-master behind this broad alliance of 60 organizations, and they will nefariously use the organic energy of people’s movements to funnel people into the Democratic Party. The implication is that the other groups in the alliance were either “duped” or are in on the conspiracy. Narratives like this can catch hold in movements only when they become primarily interested in being the “righteous few” – battling society from the margins, rather than working to influence it. This was characterized by a “campaign” launched by AdBusters against Rainforest Action Network and Ruckus Society to convince these groups to “come back” to Occupy, as if choosing to engage in an alliance meant a betrayal of our “side.”

“But some of those groups support the Democrats!”

Let’s set the record straight. It is true that MoveOn’s membership, some unions and the New Organizing Institute, have done a great deal of electoral work in the past, and many of them will work to help get Obama re-elected in November. For now, lets put aside the important discussion of whether or not engaging in electoral work to some extent will be a necessary part of a radical process in this country (we think it will). We want to point out that – not only was electoral work not promoted through the national 99% Spring process (a big deal for some groups) – but electoral work is not all of what these organizations do. They are not monolithic, and they are in a process of political opening and change (some of which was inspired or accelerated by the Occupy movement). Occupy isn’t monolithic either; the experience in Zucotti or Oscar Grant Plaza does not reflect the experience across the country. The goal of mass movements is not to make every group think and organize like us, but rather to shift the balance of forces in our country further to our side; the interest in mass nonviolent direct action from mainstream groups is an indicator of success.

Spectrum of Allies.

A key lesson from the movements that came before us is that when we shift the “spectrum of allies,” we can pull the support out from under our opposition. Our goal is to get neutral groups to become passive allies, and to get passive allies to become active ones. We’re trying to influence society and pull lots of different “social blocs” in our direction. Each step is a success. When anchored in clear transformative vision and principles, a diverse movement builds a thriving society.

Beyond November.

Might there be groups this year doing electoral work using the 99% frame? Probably. Is that “allowed”? Who gets to decide? This only represents a danger to directly-democratic and horizontal movements if it’s the only thing that happens. Critiques of electoral work are reasonable and useful – but only if we don’t let them distract us from our real work, instead of complaining from the sidelines. The real question is not what these organizations do between now and November. The real question is what they will do after November. Are nonprofits learning real lessons from the experience of Occupy, both in how to collaborate with grassroots groups without dominating, and in how to build popular power?

Why did moderate groups support 99% Spring?

A large cross-section of the more moderate edge of the progressive movement – including MoveOn members and unions — are now clear that “politics as usual” no longer work, even to achieve moderate gains or to stop right-wing attacks. They are increasingly clear that an Obama re-election will mean nothing if there is not consistent direct action pressure in the streets after his re-election. The unions who were actively engaged in the 99% Spring process were not there to stump for the Democratic Party, but because they have realized that they cannot function only through the limits of the National Labor Relations Act and that they need to activate their rank-and-file to engage in the kinds of direct action that sparked the modern labour movement in the first place. That is why they invested in the 99% Spring. This is a good thing. These historical developments — that are reflective of deeper political and economic transformations (like the decay of the social welfare state) — open up immense political potential for the radical left. If we can figure out how to engage strategically and productively within these processes of re-thinking and re-alignment within the broader progressive movement, we can leave the political margins where we have contained ourselves for too long and learn to actually lead in broad alliances.

We ally with groups when we share strategy and goals, and we don’t where we don’t. If radicals distance ourselves from alliances that involve more moderate groups, we will have our eyes and ears closed to key lessons that emerge that can help guide us forward — and quickly find ourselves alone and isolated. “A Practical Guide to Cooption,” elaborates:

“The worst thing we could do right now is make Occupy Wall Street into a small “radicals only” space. We cannot build a large-scale social movement capable of achieving big changes without the involvement of long-standing large membership institutions, including labor unions, national advocacy organizations, community organizations, and faith communities. Radicals never have and never will have sufficient numbers to go it alone. We have to muster the courage and smarts to be able to help forge and maintain alliances that we can influence but cannot fully control. That’s the nature of a broad populist alignment.”

The participation of these more moderate forces — especially unions — has been crucial in giving a much more mass character to all of the most significant direct action mobilizations of our time, from the WTO protests in Seattle to last year’s occupations, and – in so doing – opening more political space for confrontational direct action. There’s a dialectical relationship between these two aspects of political activity, and — if we narrow ourselves down to one side of that relationship – we will stop the political process dead in its tracks.

A challenge of any social movement is in who gets to define its objectives and parameters. The danger in reaching out to broad numbers of people means that lots more folks identify with the movement and spearhead their own action to move it forward. In the absence of good organizing from the Left, a political vacuum can always pull people in one direction or another. If Occupy and other radical currents do not put forward an accessible and compelling way to engage in more systemic change, the vacuum pulls people to the center. One account that was critical of 99% Spring citied that a host brought Obama buttons to a training (and falsely insinuated that this was done on a mass scale at all the trainings). The presence of political buttons at an event can only be perceived as an actual threat if we aren’t providing a credible and compelling strategy ourselves. If your movement can collapse from a few buttons, you’re in trouble! We hope fears of co-optation won’t be mistaken for radicals simply not organizing well. Getting out-organized is not the same as being co-opted.

Learning from our experiences

Two of the challenges that we encountered in the 99% Spring process were (1) developing a shared framework out of the many different (and sometimes contradictory) perspectives of the participating organizations and (2) the contradiction between scale and depth.

1. Navigating Different Worldviews and Building “the 99%”.

One of the most challenging, frustrating, and exciting aspects of the 99% Spring process was the need to develop curriculum that spoke to the different perspectives and stories of a diverse group of organizational partners: low-wage immigrant workers, union workers organizing to hold onto contracts, middle class white Progressives, homeowners facing foreclosure, public housing residents and more. This was a chance to work on some of the political challenges that have plagued both the mainstream progressive movement and the Occupy movement, in which the dominant stories focused on the recent collapse of the “American Dream” due to the banking crisis and left out large segments of our society who never had access to that Dream in the first place. This was a mass-scale effort to revise this story into a more inclusive one — one that includes the ecological crisis, migrant workers, unemployed, and many others.

It was also a chance to push ourselves beyond our normal comfort zones as Left educators. On the Left, many of us are accustomed to doing political education and skills training intended for sympathetic bases. We have developed effective ways to talk about the history of white supremacy in this country; the exclusion of workers of color, women and immigrants from labor protections and from much of the labor movement; the ecological crisis; and the development and impact of U.S. imperialism. Much of our existing work is well suited to its task, but often does not provide “a way in” for other social blocs in society — middle class folks who are tasting new experiences of downward mobility, people newly alarmed about the global climate crisis, or others who are invested in an ‘American Dream’ that has gone sour. This challenge is uncomfortable for the Left. It requires us to tell a story that speaks to white middle class progressive activists and environmental organizers and anti-corporate activists. And we need to do more than just speak to their issues. More importantly — we need to care what narratives they use to interpret U.S. history and to understand our world today.

We’re proud of the outcome. The curriculum introduced thousands to our movement histories in this country, engaged a range of voices, and shared a people-powered theory of change that includes real tools for street mobilization and nonviolent direct action.

There are not just different perspectives between different groups in our society (and the alliance); there are actual contradictions in worldview, so developing a shared story was an immense challenge. You can see the story 99% Spring came up with here. Of course, alliance members on all sides would agree that the narrative is far from perfect. We would have needed much much more time than we had on this project to do that integration in a meaningful way. The speed of the project was a challenge in itself. This story contains some things that make us uncomfortable as Leftists — like talking about the still-to-be-realized promise of democracy in the United States — but those are the kinds of discomfort we need to engage if we are going to figure out how to speak and — more importantly — listen to the tens of millions of people who our movements need to reach in this country. Finding compromise on all sides, while maintaining our shared political integrity is a wonderful project to engage in.

The 99% Spring curriculum development process didn’t push us to abandon our core political commitments, but it has pushed us to: A) Figure out how to speak to our core political commitments in a way that can actually communicate to broader populations and B) To actually care about the core political commitments of the other groups that are a part of the broad united front that we so desperately need.

2. The challenges of working at a large scale

99% Spring produced over 900 trainings, online materials, held 21 training-for-trainers events teaching 1,371 trainers, and over a thousand actions. That’s a lot of stuff. But what about quality? Training people to take direct action is a challenging process that requires skill and experience. When people engage in nonviolent action, they are putting their bodies on the line — and taking real risks. They risk their safety, their livelihoods, physical violence, emotional trauma, or legal repercussions. For these reasons, within the direct action training community, we’ve done our best to have a high bar for trainings that are tailored to meet the specific needs of the group taking action. In some ways, the idea of building a national curriculum to be implemented in nearly 1,000 trainings seemed like a contradiction. Many of us were concerned with quality control; that by deputizing the 1,300 people who opted-in to our training-for-trainers as “direct action trainers” that we might do the movement a disservice.

And yet, we also know that building a mass movement means people taking action on a scale we haven’t seen in a generation. In moments of social upheaval, many take action without any training at all; the opportunity to reach such a broad cross section of people isn’t something to dismiss. A key insight of online organizing is the idea of scalable organizing — that when we engage 100,000 people, even if the majority of those people simply shift their attitudes to be more open to direct action and sympathize with street mobilization rather than being turned off by it, we can make a major shift in culture in this country. This is a part of shifting the “spectrum of allies.”

The balance that was struck was to offer resources for some of the “higher risk” civil disobedience, but not include curriculum about arrest and the process of going to jail. While some have criticized this for producing a “vanilla” training, it seemed irresponsible for new trainers across the country who may not have any experience with the legal system to give this kind of information. Our hope is that the training whet the appetites of many to seek out the next steps in training. We’re still learning about the right balance to strike — but we take the massive amount of actions that resulted from 99% Spring (over one thousand!), and the added participation that it offered to the mass mobilizations on shareholder meetings in recent and upcoming weeks as an indicator of success.

Did the 99% Spring accomplish anything towards the demands of the moment?

1. Offering support to frontline communities leading massive action.

Many groups rooted in working class communities and communities of color engage in direct action in a way that invites others to join. These groups are leading the charge, developing the strategy, and tactically supported by a much broader alliance of groups than before. 99% Spring was successful in offering a doorway into this work for thousands of people. For example, in the Bay Area, groups like Causa Justa / Just Cause have been leading ongoing campaigns against Wells Fargo, in collaboration with groups like ACCE, have harnessed 99% Spring to continue building the pre-existing coalitions between Occupy SF, community groups, labor, environment, and others. On April 24th, a mass mobilization using civil disobedience took over the Wells Fargo’s Annual General Shareholder’s meeting. The genuine and strategic collaboration with labor yielded exciting moments, such as the janitors that work to clean the bank buildings downtown going on strike and joining the mobilization. MoveOn members did helpful email blasts in support of the action, and most Bay Area organizers have been unconcerned with “co-optation” because the message, strategy, and leadership is clear. Actions like this are happening across the country, with communities of color engaging in the “99% Power” campaigns and actions at shareholder meetings. 99% Spring did not create these actions but has certainly supported their growth. The protest at the Bank of America shareholders meeting today (May 9th) in Charlotte, North Carolina is an example of similar alliance-building dynamics we should all aspire to.

2. Action.

In the week after 99% Spring alone there were more than 1,000 actions at banks, fossil fuel companies, Verizon, Walmart, GE, and other pillars of the 1%. So far we’ve seen that 99% Spring has not been training for its own sake, but is actually moving people into action that is aligned with movement objectives. The 99% Spring program was explicitly designed to offer people tools to design their own actions based on local concerns, as well as link people to existing national campaigns.

3. Broadening “the 99%”.

Groups got to experiment with telling a fuller story of “who is the 99%” — deepening the mainstream narrative. Previously, dominant stories focused on the recent collapse of the American Dream in the banking crisis, and left out large segments of our society who never had access to that Dream in the first place. This was a mass-scale effort to revise this story into a more inclusive one — one that includes the ecological crisis, migrant workers, unemployed, and others. While the 99% Spring’s story of the economy might not be “the perfect analysis”, it is a massive step forward at forging a more mainstream consensus that integrates, race, class, gender, ecology, and more into its world view.

4. Scale.

Grassroots movements have been a bit slow to catch onto the logic and insight of scalable organizing that informs much of the online work of national groups. If we are organizing one direct action training, the goals might be very specific to move that community to a higher level of action, strategy, and vision, with deeply tailored curriculum to that constituency. This will always be the core of direct action organizing, and is often the glue that holds movements together. But this can be complemented by the shifts of scale that can happen with large projects such as 99% Spring. We need both kinds of projects.

Were we fully successful in all of these experiments? No.

When you’re coordinating thousands of trainings, there are bound to be some negative experiences. A standardized curriculum cannot meet everyone’s needs. Quality control with trainers is difficult. The project could have collaborated intentionally with Occupy General Assemblies and avoided much confusion while reinforcing Occupy group process.

Were they the right experiments to try? Yes.

99% Spring was many things to many people. The effort to broaden who the 99% is, directly meets a key political challenge of our moment. While we believe we need to ensure that “the 99%” isn’t default-defined as only middle class people with middle class concerns, we also need to make sure that our radical friends understand that “the 99%” includes many in society who do not think exactly like we do. We should embrace that diversity, and struggle with the contradictions proactively. The effort from the Left to find ways to communicate new world views and new ways of imagining the future is another key question that this project helped advance. It also helped to build multi-sectoral alliances that include leadership from working class communities and communities of color at the strategy table.

Onward!

Uncomfortable alliances are not just necessary; they reflect and speak to the tremendous possibility of our political moment. The experience this week with May Day illustrates our point: May Day actions in areas that involved deeply rooted alliances between labor, immigrant groups, and community organizations were vibrant, well sized, and got largely sympathetic public attention. Largely, actions in places that lacked this collaboration weren’t as successful. Our goal therefore isn’t to “purify” the 99% movement to keep radicals in our comfort zones, but to break it open, to make it accessible to the leadership of people of color and working class organizations that are in tune with the needs of huge sectors of our society. In doing so, we shift society closer to our transformative visions. Despite the challenges and contradictions of 99% Spring, it moved the ball forward in that direction. These experiments are the playground for innovation that we sorely need to re-imagine our society and the movements that will bring it into being. A genuine radical imagination holds space for those who have not yet come to adopt the entirety of our worldviews, and sees those close to us as potential allies, rather than enemies. If we really want to take on the power structures in our society, we’re gonna need a lot of people. Learning how to work together is part of the process that births a new world.

Harmony Goldberg and Joshua Kahn Russell are organizers and educators in movements for social change. The views in this article are their own and do not necessarily reflect those of the organizations they work with.

This article first appeared on ZNet.