As I write this, I am at the tail end of another Clown Therapy project, and once more find myself gnawing on questions of sustainability and propagation. Many projects in the expressive arts have a built-in lifetime, and a part of the pleasure arises out of the pre-knowledge of the project’s life expectancy.

Clown Therapy, projects, however, are not wrought, like a performance, but rather exist as a process, like the water cycle, where beings are drawn together, change, affect and are affected by their environment, are lifted up, then are quite literally expressed. Like water, the process itself does not need to have the same exact people in it all the time to feel continuous, although like water, repeated action in the same place and close in time creates clearer channels and direction.

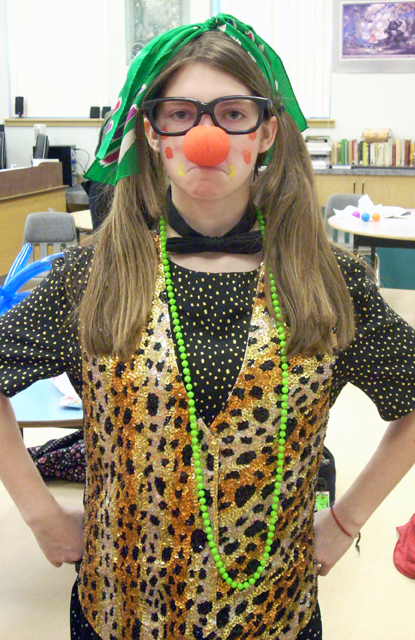

In essence, “Clown Therapy” or “Clown Care” refers to any number of project types that involve joy, a red nose, and a desire to ease suffering. They exist all over the world in many different formats, in hospitals, veterans’ organizations, theatre companies, war zones, eldercare facilities, orphanages, community centers, mental health organizations, and even schools. Although I have had the honor of working alongside, learning from, and mentoring incredible clown therapists in all of these contexts, my current longterm (I hope!) clown therapy project partners high school students (including youth who are at risk) with people in eldercare facilities living with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia. This extraordinary project is the brain child of two educators in the Okanagan Valley of British Columbia, Linda Beaven and Sandra Richardson, who decided 3 years ago that a school-based clown therapy basic training program would help students develop a sense of belonging and of community, as well as growing their interpersonal skills, courage, kindness, and reasons-to-come-to-school, in addition to being a supportive part of the mental wellness for the folks living with dementia. I have had the privilege of being the project designer and lead teacher.

Our first year, the bulk of the training was after school, and took place over several weeks. The impact was beyond our wildest expectations, especially on the students who had been struggling the most with challenges in life and at school (you can read the follow-up article on page ten of the Penticton Western News here. The following year, we tried a different structure, and the training program was combined with arts-based academic learning for a social studies/humanities class populated with kids with a variety of life challenges. Although the project reached more students, had a longer life-span, and strongly impacted the students’ self perceptions and their success in school, the connection to the community suffered. We could not all go at once, some students were not suited for the direct interactions, we could not go during school hours so scheduling became a big challenge (scheduling two dozen teens is more than twice as hard as scheduling one dozen!). In the first year, students got credit, which got them in the door, then fell in love with the direct contact, which kept them coming.

In the second year, students were required to participate in the training, because it was part of the class, but it was hard to get them to come outside of school hours for the direct contact, so many of them did not have the opportunity to fall in love. So, greater impact in many ways on the “student side” of the equation, lesser on the “community side”.

This year, all of our parameters had to shift-school, scheduling, time of year, recruitment, etc-and as a result, our enrollment and training depth suffered. There were days that I wondered if we were going to have any measure of success, especially as the time of year (spring) has meant that concerts, sports, final projects, back homework, jobs and job hunting were also competing with us for our in-school/afterschool time slots. However, there is a depth of vulnerability, of poignant connectivity that participants discover in this kind of work, even in the just the prep exercises. End result for our intrepid little band this year: some only got workshop time, but felt moved and awakened in new ways. Some got to have a single visit with the folks in the eldercare facility, and experienced the excitement and wonder of this type of interaction in the way one discovers a secret and wondrous landscape. The “one visit” students didn’t get the chance to really find their way, but at least they got a glimpse of what could be. One student was able to make to visits, and during the second, she blossomed, and began what I hope will be a lifetime interest in sweet, silly, quiet, loud, goofy, supportive, listening joy (I call it “dog love”).

Of course I want more for her, for them all. So we have begun to toss around new ideas. What if it was to two or 3 week sessions, separated by a few weeks? What if we ran the program through the school’s drama department? What if I sought out some additional sponsorship? What if a business student helped us with the paperwork and scheduling and so on? What if we could tap into a youth jobs program so they could have this be their part-time employment? What if ….

Regardless of what happens in the Okanagan Valley, there is sure to be some sort of Clown Therapy or Clown Care or Clown Doctor program in a large city near you. Even though they are not all alike nor necessarily adding new clowns, check them out. Watch, take a workshop, fill up to the brim with the amazingness that happens. And of course, you can contact me with a question or thoughts if you’d like!