The latest Labour Force Survey numbers released by Statistics Canada last week show that as of last month, the employment rate of most Canadian working-age women (25-54) has fully recovered since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This is undeniably good news. Women’s employment took a greater hit earlier in the pandemic, accounting for almost two-thirds of all job losses by this spring, and was slower to recover. That’s partly because women are more likely to work in the economic sectors — such as retail, food service and travel and tourism — that were forced to shut down due to public health measures, and partly because with schools and child-care centres episodically and unpredictably closed, women have typically done more of the unpaid work of caregiving.

But is the she-cession over? No.

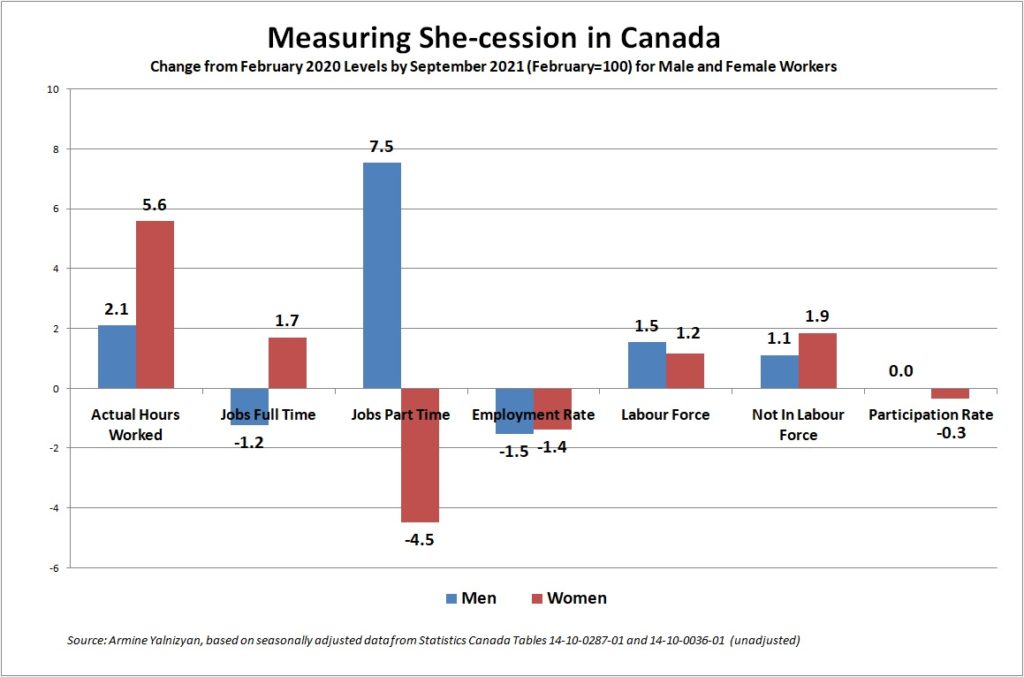

In some ways, women have done better than men in over the past 18 months. But overall, about twice as many women have dropped out of the labour market since February 2020. The labour force — which is comprised of those working or looking for work — now has 113,000 fewer women, compared to a decline of 53,000 men.

About 116,000 more women had full-time work in September 2021 than in February 2020, but approximately 103,000 fewer women had part-time jobs. Meanwhile, about 107,000 fewer men were working full-time, while 95,000 more men had part-time work.

It should be noted that they’re not taking jobs from each other. Men’s and women’s full-time and part-time work are in different sectors. For example, men are picking up more part-time work in construction and transportation, while women’s full-time work is expanding in the Care Economy (generally, the health and education sectors). And while the rate of growth in part-time work for men looks impressive as a percentage, it started from a relatively small number in February 2020. More women are likely to be working part-time than men.

It’s also good news that the employment rate — which measures the share of the total working-age population who are employed — is closing in on the pre-pandemic benchmark. September’s employment rate was 60.9 per cent, less than one percentage point lower than the February 2020 number. In fact, by September 2021, we had just regained the number of jobs we had before the pandemic — 19.1 million people were working.

But we shouldn’t take that as our cue to stop thinking about the need for more job creation. Canada’s working-age population grew by 440,000 more individuals aged 15 and older since February 2020. To get our employment rate back to pre-pandemic levels, we would need 273,000 more jobs than we had in February 2020. We’re getting closer, but there are bottlenecks in the system, some of which we may be able to address if we understand them better.

Older women at the heart of she-cession

Looking at age groups separately shows three important, clarifying trends:

Teens and young adults are doing well compared to previous recoveries, especially among young women. That’s partly because the cohort of 15- to 24-year-olds has shrunk by 40,000 people, and more of them returned to school in September so they’re out of the labour force. In addition, growing labour shortages for poorly paid or entry-level jobs means the employment rate has almost returned to its pre-pandemic level for young men (56.7 per cent in February 2020, 56 per cent in September 2021), and is actually higher for young women (59.4 per cent in February 2020, 60 per cent in September 2021).

What’s known as core-age women and men (age 25-54) are both doing well, but women are doing better. Men’s employment rate has almost fully rebounded, from 86.6 per cent in February 2020 to 86.1 per cent last month. The women’s employment rate is slightly higher than in February 2020, growing from 79.7 per cent to 79.9 per cent. There are roughly 50,000 more women in this age group working now, and 10,000 more men.

The total population of this age group grew by about 90,000 people, and an additional 200,000 have joined the labour force since February 2020. Parents of young children are an important subset of this group, and those trends bear separate analysis.

Older workers (age 55 and up) are the real story, particularly older women. From February 2020 to September 2021, almost 400,000 additional people have aged into this demographic, but only 58,000 additional people have joined the labour market, virtually all of whom are men. Not only have more women over 55 not joined the labour market, there were actually 42,000 fewer of them employed compared to February 2020. Given the growth in the underlying population, that is a stunning outcome of the pandemic’s economic impact thus far.

Ageism and the nature of the industries they’re working in may account for some of these losses, but there is something else, too. More women in this age group are dropping out of the labour market to help raise their grandkids amid the pandemic, so their daughters and sons can continue to earn a living while they struggle with unpredictable or unavailable child-care and school services.

When will this start to change, if ever? It depends on how many businesses are able to resume full operations. It depends on trends in the depth and breadth of labour and skills shortages. And it depends on how long the pandemic lasts, particularly with respect to its impact on children, schools and child-care services. We have yet to see how the fourth wave will affect schools this fall.

While we’ve known for some time that a lack of affordable, accessible child-care spaces affects working mothers of young children, we’re starting to see the impact spreading to other sectors of the workforce — namely, older adults.

It’s just another reason that there will be no recovery without a she-covery, and no she-covery without childcare.

This article originally appeared in First Policy Response and is reprinted with permission.