We can no longer rely on government alone to adequately protect nature. I say that after 40 years working as a scientist in the field of ecology and natural heritage science. Public lands are at risk; public lands do not belong to any one individual but are jointly owned by all Ontarians.

Biodiversity decline and loss of natural landscapes

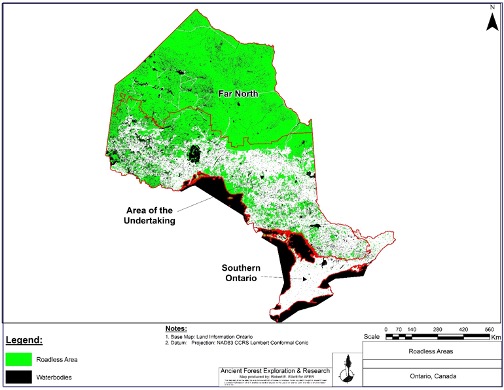

Species and ecosystem loss and decline continue at an accelerated speed, despite national and international commitments to stop the erosion of nature. Between 2005 and 2020, in Ontario’s provincially managed forest region (south of the Far North) roughly seven million acres of pristine biodiverse and carbon-rich landscapes were lost to development activities and resource extraction.

In Southern Ontario, natural landscapes undisturbed by humans, make up only about 5 per cent of the 20-million acre region. At this rate, Ontario’s pristine, public landscapes will disappear in about 70 to 80 years.

A government dependent on resource extraction revenues and jobs cannot be trusted to adequately monitor industry and protect nature.

There is a clear conflict between resource extraction, like logging of native forests, and protecting biodiversity and ecological integrity. Because of this economic dependence, governments tend to favour resource extraction industries that provide much higher revenue income compared to other users such as local inhabitants, recreationists, educators, and scientists.

Not only does this lead to biodiversity loss and degradation, but it impairs other beneficial ecological services that natural landscapes provide such as clean air and water, flood control, pollination of crops and other food-producing plants, decomposition of wastes, erosion control, carbon storage, and climate regulation. Quantified, the ecological services provided by a typical mature forest in central Ontario are worth around $20,000 per hectare (based on a TD Bank and the Nature Conservancy of Canada estimate).

Will we meet the 2030 protection commitment?

To preserve natural heritage, Canada, along with 62 other countries, committed to protecting 30 per cent of its lands and waters by 2030. Unfortunately, only 10.7 per cent of Ontario is currently protected, leaving a shortfall of almost 50 million acres. For its lack of progress on this mandate, the Ontario government recently received an ‘F’ or failing grade from a Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society assessment.

Ontario does not currently have a strategy to meet the 2030 goal. Instead, the province is pursuing a timber production policy designed to double tree fibre extraction (logging), mainly from the last remaining unlogged forests in the province. This will continue to significantly accelerate both climate warming and biodiversity loss.

Last year, the Auditor General of Ontario said the number of legally protected, species-at-risk increased by 22 percent or by 59 species over the last decade, primarily from loss and degradation of habitat.

Equally concerning is that provincial governments are moving away from evidence-based decision-making on issues that could impact ecological integrity and biodiversity forever. The significant decline in the use of peer-reviewed literature, as well as local and Indigenous knowledge by park planners will result in poorly-designed natural heritage networks and a reduced quality of life for people.

The story of the Catchacoma Forest

I am a member of the Catchacoma Forest Stewardship Committee where we have experienced firsthand Ontario’s avoidance of evidence-based policy.

The government refuses to designate Canada’s largest known eastern hemlock old-growth forest as a candidate protected area. Currently unprotected, this 1,600 acre, nationally significant, old-growth forest located in Catchacoma, Ontario is part of the Bancroft Minden Forest Company.

Designating the Catchacoma Forest as a protected area would move the Company closer to the goal of the 30×30 strategy, which will require an increase of roughly 511 000 acres within protected areas. However, the Company and the government rejected the Committee’s request for a long-term moratorium on logging and they carried out their planned logging and roadbuilding in 2019, 2020 and 2021.

At least half of the Catchacoma Forest remains in pristine condition; however, old-growth forests south of Ontario’s Boreal Forest are so rare that they should all be automatically protected, and people should be rewarded by the government for finding and monitoring them since that is not currently being done.

Who choses which land is protected?

With the goal of protecting the Catchacoma Forest, the Stewardship Committee asked: how does crown land come to be considered a protected area? And, why does logging continue in the Catchacoma Forest even though Ontario must protect an additional 50 million acres to reach 30 per cent land protection?

So we investigated the Ontario government’s process for creating new protected areas by reviewing available literature and from numerous meetings with the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (MNRF), the Ministry of Environment, Conservation and Parks (MECP), the Bancroft Minden Forest Company, and the Forest Stewardship Council.

We discovered an opaque process that prioritizes resource extraction over natural heritage protection through top-down political and administrative control. This fits in with a larger effort to accelerate resource extraction in the province as Jennifer Skene describes in her detailed essay.

Prioritizing the requests of resource industries halted the development of the Ontario Protected Areas System, which grew by less than one per cent between 2010 and 2020. Most of the processes required to create protected areas in Ontario remain undocumented and unavailable to the public even though we all have a right to participate in land-use decision making that affects public lands.

For a site to be protected, the Minister of MEC must be successfully lobbied by advocates of that site. Then an investigation determines if it should be designated as a candidate protected area. These cases may become cabinet-level decisions as it is unlikely that ministers make their decisions in a ‘political vacuum’ since they are, in fact, politicians.

Stage two, closely associated with stage one, hinges on political and/or bureaucratic discretion. MNRF must approve the site’s removal from actual or potential resource extraction. If MNRF and the local forest management company decide that resource extraction should proceed on a contested parcel, then natural heritage, recreation, and other stakeholders are out of luck. Should the potential candidate protected area make it through stages one and two, natural heritage science finally comes into play.

The basis for the decision is not the Ontario Natural Heritage Reference Manual that specifies 15 ecological selection criteria for protected areas. Rather, the designation decision is based on a 16-year-old document that emphasizes a single criterion as the first and primary filter, namely: species representation. This ignores ecosystem age (i.e. old-growth forests), human impacts, and species-at-risk, among other factors.

Currently, this single-metric approach is applied over 108 million acres in central and northern Ontario and specifies only a minimum of one per cent land protection in contrast with the 30 per cent federal government protection standard. And finally, this methodology does not require the identification and subsequent protection of rare, threatened and endangered forest and wetland types.

If MECP or the MNRF decide not to designate an area as protected due its resource extraction value, it doesn’t matter if the site is a nationally significant old-growth forest, or that it supports numerous species-at-risk, or that it has high value for recreation, education and research.

This myopic and subjective approach to natural heritage assessment results in the continued logging of pristine landscapes exacerbating the biodiversity and climate crises. The outcome is severely diminished natural heritage and low-quality parks created only after they have been stripped of their natural resources.

Biodiversity erosion and the future

One of the best examples of biodiversity erosion in a protected area is Algonquin Provincial Park – the only provincial or national park in Ontario where logging is permitted. Theoretically, parks are places where nature is allowed to evolve without interference from human activities. However, less than a fifth (18 per cent) of the Algonquin Park landscape remains free of the effects of industrial logging that has operating for almost two centuries.

Over this time period, at least 5,000 km of gravel resource roads have been built in the Park primarily to support logging. Almost 98,400 acres of Algonquin’s roadless areas (>1km from a road) remain unprotected from logging, which continues and has caused the reduction of carbon storage capacity and the loss of wildlife habitat leading to the decline of at least 29 tree and animal species in the Park.

Until the public becomes more concerned about the rapid loss of our valuable public lands, we will continue to witness the ravages of resource extraction industries at the expense of functional ecosystems, youth and future generations.

We need strong and systemic natural heritage leadership now more than ever. This work does not require an advanced degree. To get involved and make a difference, people can join one or more of the many organizations that focus on biodiversity conservation action, or start a new initiative to focus conservation efforts in your community.

No matter how big or small, your contribution to maintaining the ecological integrity and biodiversity of this incredible planet that we depend on will make a difference, particularly when the cumulative effects of all efforts are realized.

Getting involved may also get you into the great outdoors where you will benefit from the therapeutic effects of nature on both physical and mental health, you will meet new people, and you just might become happier and less stressed.