Icebergs melting, sea ice disappearing, glaciers retreating, icecaps destabilizing, starving polar bears, drowning seal pups, permafrost thawing, ozone vanishing, carbon dioxide levels rising, methane releases, sea levels rises, coastlines eroding … these are all too familiar illustrations of the face of climate change in Canada. Once conjectural, we now see many of these changes taking place in Canada.

Now, a new study lead by Susan Solomon of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in the United States, provides evidence that we are rapidly approaching a climatic tipping point, beyond which certain changes may be largely irreversible for 1,000 years. Globally, carbon dioxide (a major greenhouse gas) levels are currently at 385 parts per million (ppm) and are increasing at a rate of 2 ppm per year. This April a level of 400 ppm — the highest ever recorded — was measured by NOAA in Barrow, Alaska — a dismal climatic milestone. Climate scientists, such as NASA’s James Hansen, believe that 350 ppm is the highest safe level of carbon dioxide we can allow if our climate is to remain stable.

Solomon’s study predicts that if levels exceed 450 ppm we risk setting in motion an unstoppable chain of events, such as droughts that she warns would turn many areas in southern Europe, northern Africa, southwestern North America, southern Africa, and western Australia into a 1930’s-style dust bowl. Moreover, such effects would last not decades, but centuries. As for sea level rise, considering only the expansion of warming ocean waters (without factoring in melting glaciers and polar ice sheets) the study forecasts a rise of up to 1.0 meters. Further sea-level rises, due to melting glaciers and polar ice sheets, could be even larger but the study could not quantify these since knowledge of them is still incomplete. Solomon warns that sea level rise would cause “irreversible commitments to future changes in the geography of the Earth, since many coastal and island features would ultimately become submerged.”

Climate change and invasive species

In October of 2011 I made a presentation to the Canadian Parliamentary Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development on the intersection between climate change and invasive species. What connection do they have?

The large majority of non-native species (both invasive and not) are ecological opportunists, thriving in disturbed habitats. This is in contrast to many native species which are found in indigenous, undisturbed habitats. The effects of climate change are to increasingly disturb habitats in such a way as to favour ecological opportunists. Contemporary civilization has created large areas of such disturbed habitat such as lawns, agricultural fields, pastures, golf courses, forest plantations, highway right-of-ways, and vacant lots. This proportion of our landscape has been growing steadily. Thus, there are more and more areas suitable for faunas that thrive in disturbed environments, and climate change may further this trend. Climatologists predict that the broad pattern of climate change will be to accentuate current patterns; dry areas will experience more droughts; wet areas more precipitation; heat waves will be more severe; cold snaps colder; forest fires more frequent; extreme weather events will occur more often. Such circumstances have a disproportionate impact on native species, as many of them are adapted to the present environmental conditions.

Thus, we can expect there will be more opportunities for invasive species to establish themselves, more habitat for already established invasive species to exploit, and existing non-native species that are not currently invasive, could become so as changing environmental conditions allow them to break free of their ecological restraints. What could the results be?

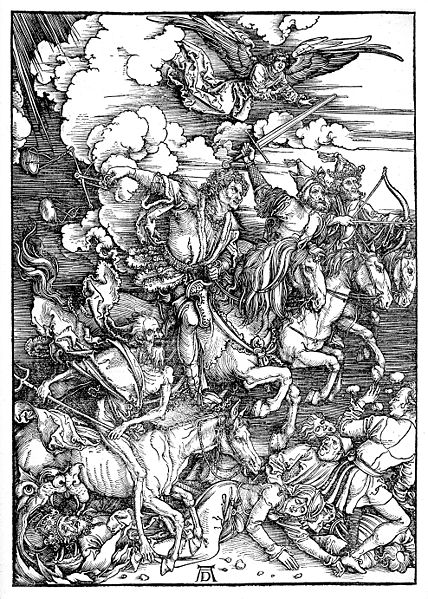

The white horseman: Pestilence

The mountain pine beetle (Dendroctonus ponderosae) is an inconspicuous 5 mm bark beetle responsible for the largest forest insect blight ever seen in North America. Over 130,000 square kilometers (an area the size of England) of pine forests in British Columbia and Alberta have been affected, as have large areas in Colorado and Wyoming — an epidemic ten times larger than ever previously recorded. Commercial timber losses in Canada alone are estimated to be in excess of 435 million cubic metres. And these millions of dead trees are not only not absorbing and sequestering the carbon dioxide that they normally would, but as they begin to decompose they release carbon dioxide. Werner Kurz and his colleagues in the Canadian Forest Service have estimated that the impact of the mountain pine beetle will be the release of a billion tonnes of carbon dioxide by 2020, the equivalent of five years of all Canadian transportation emissions. What is responsible for this ecological train wreck?

1. Poor forest management: enormous plantations of even-aged monoculture stands of lodgepole pine that provide a virtually endless, unbroken expanse of food for the beetles, and misguided fire-suppression; and

2. Climate change: the gradual warming of the climate means that the extended cold snaps that once killed large numbers of beetles during the winter no longer occur. Sustained temperatures of minus 35-40ºC for several days will kill large proportions of mountain pine beetle eggs, pupae, and young larvae. Such cold snaps were once regular in western North America; now they no longer are.

Andrew Nikiforuk has chronicled the “misguided science, out-of control logging, bad public policy, and a hundred years of fire suppression” that laid the groundwork for this infestation, and how climate change released the genie from it’s box in his superb book, Empire of the Beetle: How Human Folly and a Tiny Bug are Killing North America’s Great Forests.

When will the outbreak stop? Nobody knows.

The black horseman: Famine

Another illustration is provided by research done by Owen Olfert and Ross Weiss, entomologists with Agriculture and Agri-food Canada. The cereal leaf beetle (Oulema melanopus) is a pest of wheat, oats, and barley; the cabbage seedpod weevil (Ceutorhynchus obstrictus) is a pest of plants in the mustard family including canola, mustard, cabbage, and broccoli; and the bronzed or rape blossom beetle (Meligethes viridescens) is another serious pest of mustard plants, particularly canola. All three are non-native, invasive species. By studying the ecological tolerances of these beetles (such as their responses to heat, light, moisture, and changes in seasonal length) in combination with climate data, Olfert and Weiss calculated ecoclimatic index (EI) values that show how favourable or unfavourable areas of the country could become if there are changes in temperature and moisture, as is expected with climate change.

The figure above shows the results of a temperature increase of +3ºC, considered an intermediate value between low and high greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions scenarios for Canada by the end of the century. The results are striking. Climate change would upon make suitable, favourable, or very favourable a much larger proportion of Canada’s land area for all three of these invasive species. The economic impact of this could be very substantial since these beetles are serious pests of a wide variety of food crops.

When could such outbreak occur? Nobody knows.

The horsemen gather?

What needs to be done? Just about everything. To address the impact of climate change on invasive species we need:

1. To devote significantly greater resources to conducting biodiversity research;

2. Significantly greater funding for developing and maintaining taxonomic resources — museums, reference collections, taxonomic experts, and publications;

3. To monitor for new alien species, and for changes in the distribution of established alien species;

4. To have detailed eco-physiological information about potential invasive pests.

With the many extensive cuts to Environment Canada programs about to be implemented by the Harper Government through Bill C-38, we are moving farther from these objectives rather than closer.

Climate change has not been formally integrated into federal risk assessment and management processes under the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, a significant shortcoming highlighted by the Policy Research Initiative (PRI) in a symposium entitled Integrating Climate Change into Invasive Species Risk Assessment and Risk Management in November 2008. Now Bill C-38 proposes to repeal the current Canadian Environmental Assessment Act and replace it with a new one whose terms of reference will be significantly narrower and which, in 67 pages of terms of reference, rules, regulations, etc. makes not a single reference to climate change. The participants in the PRI symposium underscored the need to develop accurate models of climate change, develop an institutional awareness of climate change, develop biological, climatic, and technical expertise, target funding to undertake these processes, integrate climate change awareness into policy development in other social and economic sectors, and for government to foster long-term decision-making. These are all important objectives — which the policies of the present Harper Government scarcely pay lip service to, let alone substantively address.

Climate change represents a ticking time bomb in relation to invasive species, and much else. The Canada we live in has taken 20,000 years — since the end of the last glaciation — to reach an ecological equilibrium. We’ve already significantly disturbed that equilibrium. Once climate — the bedrock of the ecological world — begins to change, all bets are off as to where this may lead. It is important to develop measures such as those outlined above to backstop that risk. But, it is even more critical that we take all possible measures to minimize climate change at all. The costs of not taking action will certainly greatly exceed those of doing so.

The NOAA study clearly indicates that carbon dioxide levels of 450 ppm — which we are on track to reach by the middle of this century — will lead to an unstoppable chain reaction of droughts and rising sea level that could take hundreds – if not thousands – of years to reverse. The red horse of the Apocalypse represents war or mass slaughter; the pale (or green) horse is death. Will we let greed, stupidity, and political inaction pave the way for the arrival of all the Horsemen of the Apocalypse? The choice is ours.

Christopher Majka is an ecologist, environmentalist, policy analyst, and writer. He is the director of Natural History Resources and Democracy: Vox Populi.