In a recent TV interview, the celebrated U.S. political scientist Francis Fukuyama made what struck me as possibly the most foolish remark ever uttered on TV. And I know that’s a high bar.

“The nuclear threat, I think, is a bogeyman,” Fukuyama said in a MSNBC-TV interview about the war in Ukraine. “Of course, everybody is going to be worried about the possibility that you could eventually get there. But there are so many stopping points before you reach that point that, I think, you know, that is not something anyone should be worried about.”

Suggesting nuclear war is “not something anyone should be worried about” is stunningly foolish — and dangerous.

Fukuyama’s minimization of the nuclear threat — a stance that underlies much of the commentary on Ukraine — implies the public should relax about nuclear conflict since the chances of it are remote.

After all, according to Fukuyama, “there are so many stopping points” before we’d reach nuclear war.

The problem is he’s dead wrong about that.

In truth, there are virtually no stopping points. Things could move from a mistaken belief that the enemy has fired a nuclear weapon to an all-out nuclear war that would kill hundreds of millions of people in less time than it takes to eat a veggie burger.

That’s because the United States and Russia both have hundreds of nuclear-armed missiles on “hair-trigger alert,” ready to launch on warning.

The U.S. president “has roughly six minutes to make a decision if it appears we are under attack,” according to the late Bruce Blair, a Princeton University professor and expert on command-and-control systems for nuclear weapons.

Indeed, an accidental triggering of nuclear war — due to a false or mistaken warning signal — is the most likely way a nuclear war would begin, according to Daniel Ellsberg, author of “The Doomsday Machine” and a former nuclear war planner in the Kennedy administration.

Such an accidental war becomes all the more likely when there’s heightened tension and mistrust, leaving both sides more inclined to believe the other has launched an attack.

Earlier this month, Ellsberg said that today’s extreme tension over Ukraine makes nuclear war “a more imminent possibility than the world has seen since the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962.”

Clearly, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is an appalling act of aggression, and it’s right for the West to help the Ukrainians defend their country.

But nuclear war must never be on the table.

Germany, France and Italy have correctly pushed for negotiations towards a diplomatic solution in Ukraine. However, the U.S. is digging in, moving beyond the original goal of helping defend Ukraine to adopting the more ambitious and perilous goal of weakening Russia.

In late April, U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin said Russia should be “weakened to the degree that it can’t do the kinds of things that it has done in invading Ukraine.”

But while teaching a schoolyard bully a lesson can be satisfying, it’s a crazy idea when the bully has nuclear arms and humiliating him could set off World War III.

Ottawa, responding to persistent demands from Washington, is increasing our military spending to bolster NATO forces in eastern Europe.

Former Canadian senator Douglas Roche questions this focus on military spending, noting that “Canada already spends 20 times more on its military than on diplomacy” and this “dwarfs our contributions to the UN’s sustainable development programs.”

“Human security today does not come from the barrel of a gun. It comes from preventive planning,” Roche argued in a recent op-ed.

Many commentators insist we have no choice, that we’re already in World War III.

But we’re not. And that very suggestion is part of the dangerous downplaying of the incomprehensible horrors of nuclear weapons.

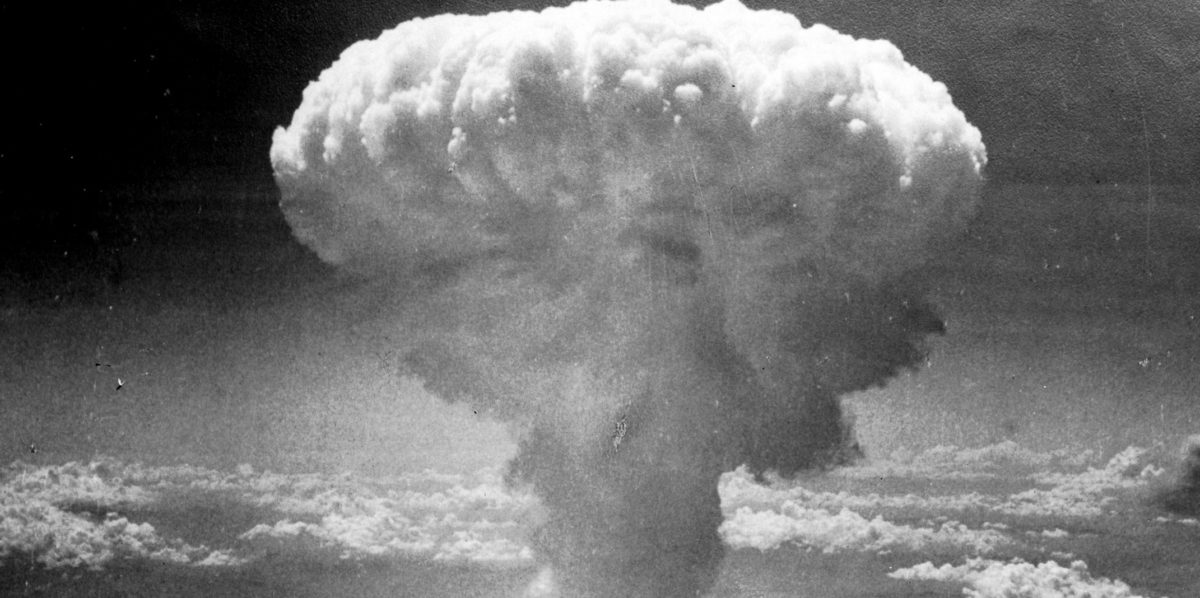

Today’s bombs are a hundred times more powerful than the ones dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. A full-scale nuclear war today could kill everyone on earth, with any survivors enduring primitive lives in a “nuclear winter.”

As Albert Einstein reportedly commented, “I don’t know (what weapons will be used in the Third World War). But I can tell you what they’ll use in the fourth — rocks.”

This article was originally published in the Toronto Star.