Content warning: The following story contains mentions of sexual assault. Please proceed with caution and care. If you require support, there are resources available.

In a just world, there would be no police and there would be no prisons. That is the basic claim of abolitionist politics.

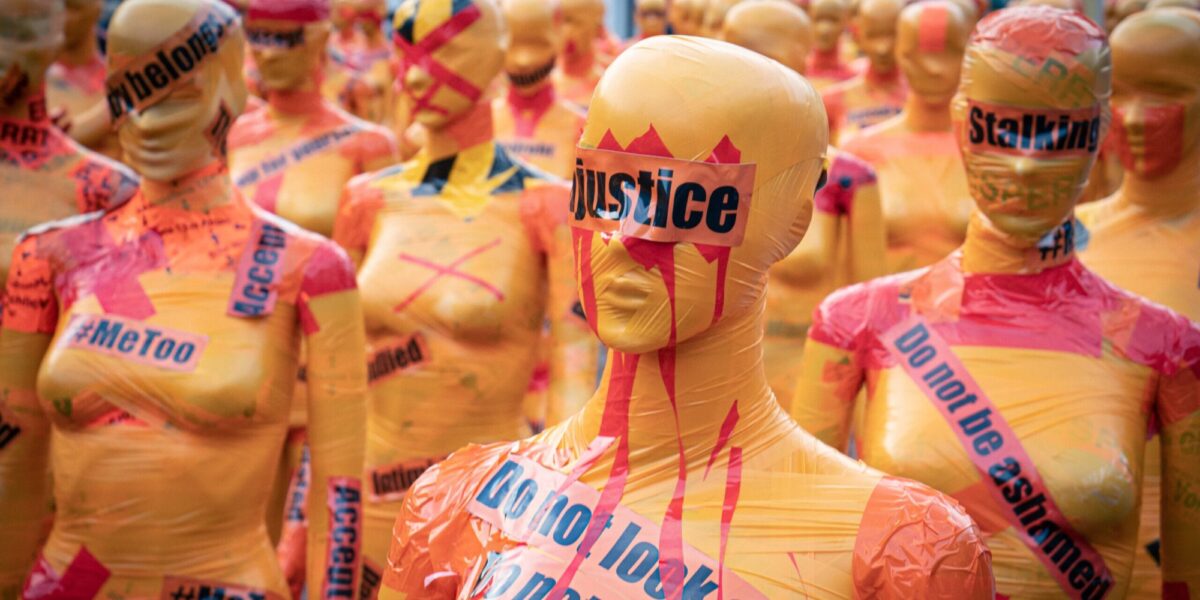

But it leaves the victim-survivors of sexual violence in the dark. In a culture where justice is dominated by the prison-industrial complex, what are rape, assault, or abuse survivors supposed to do about the violence we have endured other than report our victimization to the police?

I raise this question as a victim-survivor myself, for the benefit of other victim-survivors and our allies.

I was sexually assaulted almost two years ago, and it nearly destroyed me. In the immediate aftermath, I faced an excruciating decision about who to tell. My family? Friends? The police?

In the end, I chose to tell everyone.

But I still struggle to know, all these months later, whether my decision to participate in the criminal justice system was motivated by a desire for justice or for revenge. I like to think the former; and on my better days, I even believe it. I wanted accountability; I wanted to ensure the man who attacked me couldn’t hurt anyone else; I wanted some acknowledgement that what happened to me was wrong.

As far as I know, these outcomes are only available through the criminal justice system.

In the aftermath of something as dehumanizing as a sexual assault, politics go out the window. It is only with time and healing that they re-enter the picture. And that’s how it should be.

I write for victim-survivors like me, but this is not a lecture.

In the aftermath of a sexual assault, people need to do what they need to do to survive. I write for those of us who have endured some of the worst violence this world has to offer, and now have the time and distance necessary to engage in critical reflection on whether the options available to us were the best ones. I write for those of us with the capacity to look to the future.

What justice means for victim-survivors

There’s an old joke that if you ask 10 economists their opinions, you’ll get 20 opinions: each has another hand, after all. The same is true for sexual assault victim-survivors’ views on justice. Ask 10 of us, and you’ll get 20 (or more) different views.

It’s easy to imagine that, in the immediate wake of our victimization, survivors are hellbent on seeing our victimizers punished, and nothing else. But in point of actual fact, punishment and incarceration are small—almost negligible—aspects of what we’re looking for.

Scholars have only recently begun asking victim-survivors what we think justice for sexual assault is. But their findings demonstrate as much.

The first such study in the United Kingdom, by Durham University professors Clare McGlynn and Nicole Westmarland, identified six “key themes” in how the victim-survivors they interviewed understood justice: “justice as consequences, recognition, dignity, voice, prevention and connectedness.”

Justice as consequences means, quite simply, that wrongdoing must have some effect for, or impact on, the perpetrator. This might look like punishment and incarceration—the typical outcome of what’s known as “retributive justice”—but it could also look like compelling the perpetrator to engage in mandatory counselling, pay compensation to their victim, or simply accept responsibility for what they have done.

Justice as recognition is about giving victim-survivors some acknowledgement that we have, indeed, been victimized. This aspect of justice is all about truth, and it involves both offenders as well as victim-survivors’ communities. Justice as recognition calls upon offenders to acknowledge that what they have done is wrong; and it calls upon friends, family, police, and, indeed, the general public to acknowledge, too, that what happened was wrong.

Justice as dignity flows from justice as recognition. In accessing the justice system, victim-survivors must be treated with respect and understanding for any outcome to be just. We are not just pieces of evidence, after all; we are human beings. Treat us accordingly.

Justice as voice means giving victim-survivors an opportunity to participate in the process of obtaining justice, as well as an opportunity to speak out about the harms we have suffered.

Justice as prevention is about changing the local and national communities—their structures, norms, and policies—to make crimes less likely to occur in the future. This goes beyond rehabilitating individual offenders to include broader strategies for ensuring no one else has to experience what we victim-survivors have gone through.

Finally, justice as connectedness means facilitating victim-survivors’ restoration to full membership in our communities. Especially in cases of sexual assault, victimization strips survivors of our humanity; it tells us that we do not belong in society, that we are less than. Justice tells us the opposite: it tells us that our communities are our homes, that they support us, and that we benefit from their protection.

The takeaway from these overlapping themes is this. Abolitionism is pro-survivor because it operationalizes what the victim-survivors of sexual assault are saying: that we don’t want to see more prisons; we want to see restorative justice.

Restorative justice in theory and practice

In essence, restorative justice is about repairing the harm that an offender has committed, promoting healing for the victim-survivor, and fostering accountability on the part of both offenders and victim-survivors’ communities. Where retributive justice is about punishing wrongdoing, restorative justice is focused on undoing the social damage that crime causes to people. It’s a reparative rather than an adversarial process that sees crime as a failure by society to care effectively for its members, victim-survivors and offenders both: a failure that must be resolved through individual and structural reforms.

Canada’s criminal-justice system already has limited forms of restorative justice built into it.

Take conditional sentencing orders. These are a restorative-justice alternative to incarceration that allow an offender to serve their sentence under strict supervision (typically, some form of house arrest) in their home community. CSO’s, as these sentences are otherwise known, spare offenders the violence of actual incarceration while allowing courts to impose rehabilitative and reparative conditions on them: for example, community service and treatment programs or reparations to victims.

For Indigenous offenders, the alternatives to incarceration include a more expansive range of community-based sentences. These options are founded in what are known as “Gladue principles.” The Gladue principles require sentencing judges to consider an Indigenous offender’s individual circumstances, for example, how settler-colonialism has created conditions under which Indigenous persons are more likely to come into contact with the criminal-justice system. They also require judges to take into account what an offender’s home community thinks would be an appropriate sentence, as well as how the laws of an offender’s Indigenous Nation might be applied.

All of these are meant to provide alternatives to imprisonment; and to create space for such practices as Indigenous sentencing circles, which bring together victims, offenders, and members of the criminal justice system in a process that nurtures healing amongst all involved, grants victim-survivors a voice, and allows offenders to make amends for what they have done.

The foregoing offer glimpses of what restorative justice looks like in practice. But, by themselves, none of the sentencing practices I have described will solve the problem of over-incarceration.

For one thing, in the almost 25 years since the Supreme Court of Canada first promulgated the Gladue principles, the overrepresentation of Indigenous offenders in penal contexts has gotten worse, not better—a sign that the principles alone are not enough. For another, Parliament has seriously limited the availability of things like CSO’s by imposing mandatory minimum prison sentences in a range of circumstances—most notably for drug offences.

Clearly, more radical solutions are needed. Ones that introduce structural changes to society in order to prevent violence from occurring in the first place, and to heal the damage people suffer when it does.

Abolitionism advances just such a solution: not just for the easy cases, but for the hard cases, too.

No one belongs in prison. Not even rapists. Everyone deserves rehabilitation and restoration to full community. Even the vilest abusers.

Because victim-survivors deserve more than to see our victimizers locked up. We deserve justice. And justice is one thing prisons, in so far as they are vehicles of injustice, simply cannot deliver.

To report or not

If you’re a sexual assault victim-survivor reading this column and wondering whether to report your experience to the police, I’m afraid I don’t have an answer for you.

I reported mine, and all these months later, I’m very glad that I did. But the decision whether to report or not is a decision that each victim-survivor must make for themselves.

Any abolitionism worth its salt must take seriously the realities of the world victim-survivors inhabit. And that is a world in which justice for sexual assault—restorative, punitive, and otherwise—is as a practical matter usually only available through the criminal-justice system.

My abolitionism doesn’t take issue with the decisions individual victim-survivors make about whether to participate in that system. It takes issue with the fact that that system is currently the only game in town.

And maybe, in the end, that’s what matters. Not that we criticize what victim-survivors have to do to survive, but this: that we join hands and dream, together, of a better world.