It is the holiday season and folks might be looking for worthwhile, recent movie releases. That’s one excuse for temporarily abandoning my watch on politics.

Another is the excruciating nature of world news, these days, especially from Gaza.

Since October 7, I have written some words about the brutal war taking place between Hamas and Israel, but not too many.

The death toll in Gaza is so staggering that even countries such as Canada, which normally take Israel’s side, cannot stomach it. Canada has now, belatedly, joined almost the entire world in calling for a ceasefire.

Tragically, the current Middle East conflict does not appear about to end anytime soon. I fear there will be more than a few occasions to do more reporting on it in the New Year.

For now, I am inclined to take the advice of the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, who ended his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus with the words: “Wovon man nicht sprechen kann, darüber muss man schweigen” – “Whereof one cannot speak, one must remain silent.”

Big budget, Oscar bait

And so, to the world of film. It is a world where there is lots of action and emotion. But it would be unwise to confuse that world with reality.

The motion picture in question, for today, is the much-ballyhooed Hollywood blockbuster, Maestro.

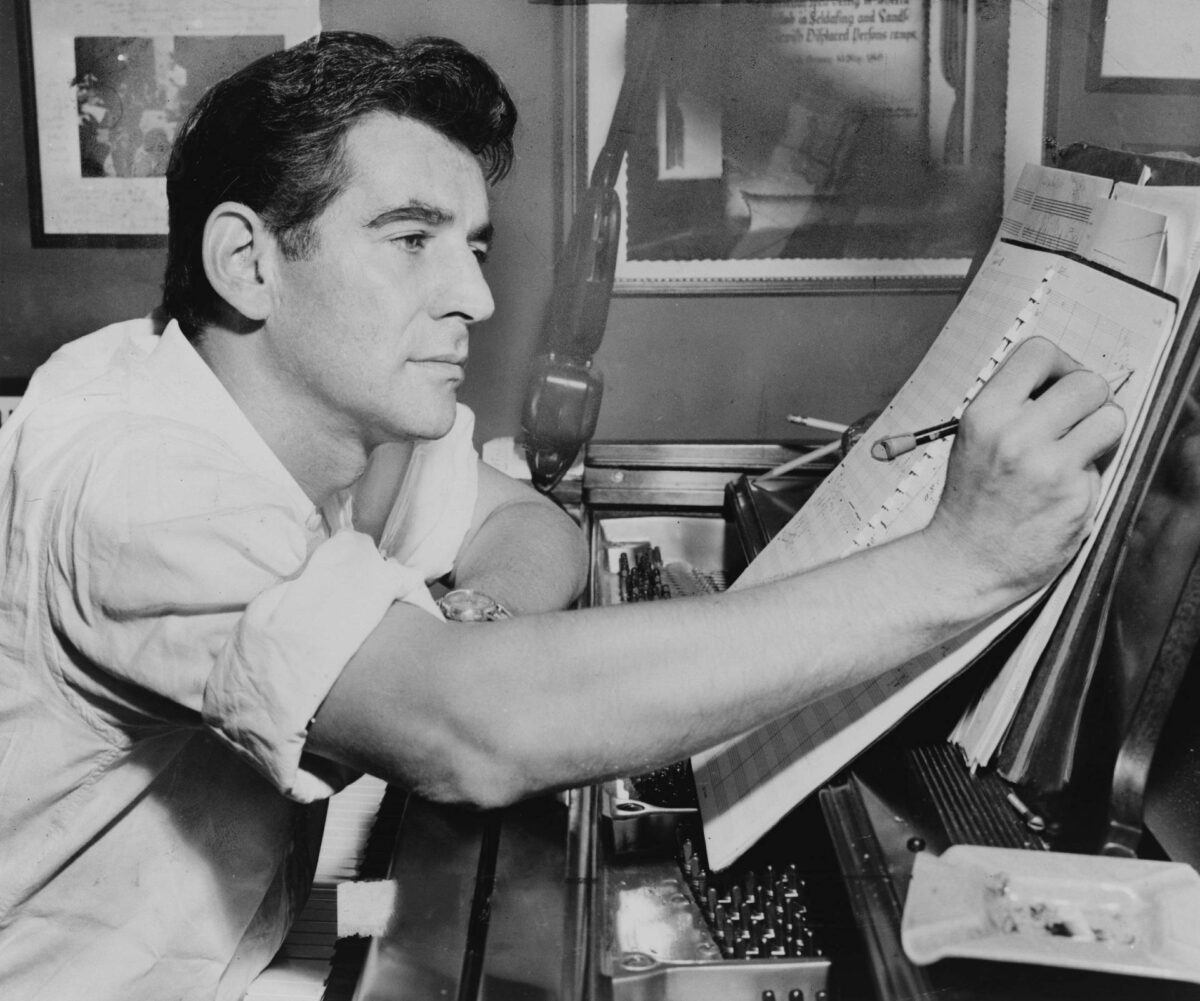

This big budget project, starring and directed by über A-lister Bradley Cooper, purports to tell the story of composer, conductor and music educator Leonard Bernstein.

The internet giant Netflix produced Maestro, but distributed it in theatres before making it available online. The film has done well in movie houses. It is Netflix’s most successful and profitable theatrical release.

Hollywood insiders describe flashy productions that feature big, bankable stars – such as Maestro – as Oscar bait. And if winning awards has been the producers’ goal, they’re scoring big so far.

The film has been nominated for about 60 awards, among them four Golden Globes, including Best Dramatic Film. Success at the Golden Globes often foreshadows wins at the Academy Awards, which will name its nominees in 2024.

The critics have been similarly favourable to Maestro. Websites that aggregate reviews give the picture a better than 80 per cent positive rating.

All that could motivate you to put Maestro high on your holiday viewing list. And you might enjoy the film as a well-paced, sometimes heart-wrenching portrait of a troubled marriage between two talented people, Leonard Bernstein and his wife, actress Felicia Montealegre.

In the latter role, the preternaturally talented British actress Carey Mulligan steals every scene she’s in.

But notwithstanding Mulligan’s truly Oscar-worthy performance, this writer found the film to be deeply disappointing.

Here’s why.

A childhood hero who made music exciting

As a kid, not yet a teen, I watched a good many of Leonard Bernstein’s live, black-and-white television shows with rapt attention.

The composer of West Side Story and conductor of the New York Philharmonic had a knack for explaining musical concepts in a way that was not at all dry, complicated or technical, but never simplistic or dumbed down.

In those TV shows, Bernstein mostly covers classical music – but not exclusively. I remember well one show where he explains what makes jazz tick, and another where he recounts the origins and history of the Broadway musical.

The lessons I learned from those programs have stayed with me for more than 60 years.

In his show on jazz, Bernstein starts by saying he does not intend to take the familiar historic approach. He will not repeat the cliché-ed story of how jazz moved up the Mississippi from New Orleans to take on the world.

Instead, Bernstein will “examine the musical innards of jazz, to find out, once and for all, what sets it apart from all other music”.

Bernstein “loves jazz”, he says, because “it is an original kind of emotional expression, never wholly sad or wholly happy.”

“Even the blues,” Bernstein tells us, “have a robustness and hard-boiled quality that never lets it become sticky sentimental, no matter how self-pitying the words.”

About 25 minutes into that TV show, after explaining the blues scale, musical colours, and other concepts, Bernstein gets to what he calls the heart of jazz: improvisation.

Unexpectedly, but very much in character, he uses a well-loved piece of classical music to demonstrate the idea: Mozart’s variations on the simple tune “Ah, vous dirai-Je Maman” better known to most of us as “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star”.

Bernstein wants to show what it means to take a tune and use it as the basis for multiple, new, original tunes. Unlike Mozart, jazz musicians create their solos – or, to put it differently, they compose their new tunes – in real time, live.

On the TV show about Broadway musical theatre, the eminent conductor explains how the modern musical evolved out of the vaudeville-era variety show.

Originally, way back in the early 20th century, Bernstein tells us, musicals had the flimsiest and silliest of plots, and their songs were only loosely related, if at all, to the story lines.

Then, in the 1940s, the Broadway musical became a lot more like grand opera, with compelling stories, recurring music motifs, and songs that advanced the plot and helped establish characters’ personalities.

Bernstein cites such modern musical theatre examples as The King and I, Showboat, and South Pacific – shows that are frequently revived to this day. He might have also cited his own contributions to the genre: On the Town, Candide, and, most of all, West Side Story.

The persona the real Leonard Bernstein projects in those long-ago broadcasts is warm, generous, intelligent but not condescending, erudite without being pedantic, and, above all, passionate about music. And one meets very much the same person in Bernstein’s essays and books.

That person genuinely wants his audiences and readers to love, appreciate, and understand music as deeply as he does.

Reducing an artist to his flaws

Bernstein’s knowledge and enthusiasm had a significant impact on a very young me, as it did on many others.

But that inspiring persona is almost entirely absent from the Bradley Cooper version of Bernstein we meet in Maestro.

Maestro’s Leonard Bernstein seems more caricature than characterization. He is self-centred to the point of narcissism, borderline cruel to those he claims to love, duplicitous, self-pitying, and, overall, thoroughly unlikable.

Some mid-20th-century television personalities, most famously Edward R. Morrow, heedlessly puffed away on cigarettes during their live broadcasts. Bernstein did not. Yet, in Maestro there is hardly a scene in which Cooper’s Bernstein is not chain smoking to beat the band.

Off camera, Bernstein was, yes, a person of his time, a time when smoking was entirely de rigeur. I remember that time – I coughed and wheezed through much of it.

But to tell a compelling story, was it really necessary for the filmmakers to rub our noses in Bernstein’s tobacco addiction, to the point where some viewers might develop psychosomatic symptoms of COPD?

The omnipresent smoking was a distraction from the film’s action and dialogue. As was the artistic choice to resort to a kind of faux naturalism, whereby multiple characters frequently talk over each other – to the point where it was impossible to hear what anyone was saying.

Much of the film is dedicated to Bernstein’s promiscuous sex life and the tragic impact it had on his marriage. At one point, Cooper’s Bernstein goes so far as to say to a toddler in a stroller he meets in Central Park: “I slept with both of your parents!”

Now, the fact is that there are many people out there with complicated personal lives. And there are plenty, as well, who take advantage of the trust and adoration of those close to them.

Some of those folks are accountants or factory workers or plumbers or bus drivers or nurses or shop clerks. Maybe, today, someone, somewhere, is making a film about one of those folks.

However, Leonard Bernstein is not a good subject for a film because of his many imperfections.

What makes Bernstein worthy for portrayal on screen is his creative genius as a conductor, composer, and public educator.

Precious little of those attributes makes it into this film, however, and more’s the pity.

Progressive politics and a fascination with Mahler

One had the right to expect that Maestro’s screenwriters and Cooper would have at least been interested in Lenny and Felicia’s well-documented political radicalism.

The couple famously held a fundraiser at their Upper West Side apartment for the Black Panthers. Journalist and author Tom Wolfe sarcastically coined the phrase “radical chic” to describe that event.

But this film has no time for politics, just as it has very little time for the amiable and friendly Bernstein who brought the complex world of music alive for millions.

Toward the end of Maestro, the filmmakers partially redeem themselves with a long scene in which Bernstein conducts the London Symphony Orchestra performing a choral passage from Gustav Mahler’s Second Symphony, the Resurrection.

It was a beautiful six minutes. And six minutes of unedited classical music is an eternity for a mainstream, commercial Hollywood production.

It has been reported that Cooper worked on learning Bernstein’s mannerisms on the podium over a period of years. The film credits Canadian conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin as a “conducting consultant”.

The real Leonard Bernstein devoted much time and effort to the works of the great romantic composer Mahler.

Bernstein often said he felt a strong affinity with the composer of the Resurrection Symphony. Perhaps that was because Mahler, too, was a Jew. As well, like Bernstein, Mahler had been a conductor of the New York Philharmonic (from 1909 to 1911).

You will not learn any of those facts from the film, however. Maestro expends no effort to help us understand its main subject’s fascination with the composer of the music that serves as its finale

The screenwriters would have no doubt considered it uncool and old-fashioned in the extreme to work such expository information into their script.

They were almost exclusively focused on over-the-top emotion and sexual escapades.

If that approach to storytelling is your cup of tea, you will love Maestro.