Sport has always been a matter of deep social significance. In contemporary society there are few individuals who do not, directly or indirectly, encounter elements of sport in their daily social lives. Some may be actively involved as participants in some kind of sporting activity. Others may be spectators at sporting events or consume sport via the mass media. Some may volunteer as coaches, referees, or executive members of a sporting organization. Of course, there is also a segment of the population that is not particularly interested in sport. However, even those individuals find that sport in some way is a part of their lives, through such regular occurrences as sporting news and sport-oriented conversation in family or work settings or through the enthusiasm demonstrated by others about major events such as the World Cup of Soccer, The Olympic Games, or the Stanley Cup Playoffs. Clearly, sport has some influence on the lives of most throughout the world.

Yet among left and progressive circles there often exists a certain haughty view towards sports as a field acceptable to political activism or as a social phenomenon of great magnitude and complexity. Nevertheless, this article starts from the perspective that, contrary to conventional dogmatic party line, professional sport is not just another diversionary tactic of the capitalist bosses doping workers to forget the class struggle – ‘an opiate of the masses’ – but an important component of people’s lives and culture, and a crucial site of ideological struggle.

This week’s confirmation that there will be another NHL lockout is a perfect example. Watching hockey, in arenas or on television, is a leisure-time activity for an overwhelming number of Canadians. During the NHL playoffs, hockey functions as almost a religion, as those who enter its realm treat its symbolic plot as an inextricable part of the national  culture. It is omnipresent in what is presented as the Canadian consciousness, routinely lauded as “Canada’s game,” and indeed – as many recent immigrants will attest – paying attention to the NHL is an important signifier of a Canadian identity, for better or worse.

culture. It is omnipresent in what is presented as the Canadian consciousness, routinely lauded as “Canada’s game,” and indeed – as many recent immigrants will attest – paying attention to the NHL is an important signifier of a Canadian identity, for better or worse.

Indeed, it is no coincidence that projects around the construction of Canadian nationalism are regularly linked to hockey, an issue to be explored further in the pages of Left Hook. This relationship between Canada and hockey is routinely cashed in on, whether by Tim Horton’s advertising campaigns (often peppered with the mythology of Canadian multiculturalism), politicians eager to seem like ‘normal’ Canadians (who can forget Jack Layton shoving someone out of the way so that the camera could catch him cheering for the Canadian Olympic hockey team), or the military drumming up support for the war in Afghanistan (with the enthusiastic support of right wing pundits like Don Cherry.)

Hockey and Capital

Clearly, then, whether we like it or not, hockey has profound influence on the lives of most people in this country. It is little surprise, then, that this sport has become a multi-billion dollar industry in which highly-trained, highly-valued athletes chase a puck around a potentially priceless development site. Where hockey was once primarily an object of passion and of individual patronage and whose main source of revenue was its gate receipts, it now serves as a rational strategy of capital speculation and accumulation.

Thus, make no mistake, at the heart of current conflict is the struggle between capital and labour that characterizes all capitalist enterprise. Having seen major profit growth over the past five years, the cartel of team owners wants to impose a tighter cap on player salaries, knowing that without such an agreement between the owners, each will continue offering higher and higher salaries to individual players in order to attract the biggest names to their franchise. Essentially, then, the billionaires who own professional hockey teams are afraid that a free market in player salaries will cut into their profits. At some level, of course, they are right. Under the current collective agreement, the players receive some 57% of the revenues generated by the NHL. The owners want to push that number down to 47%, splitting the extra 10% of the NHL’s nearly $3 billion in annual revenues between the 30 owners.

The players, on the other hand, insist that people come to watch them. That it is their bodies on the line when they drop down to block a 100 mph slap-shot, that it is their careers that can be suddenly cut short by one errant elbow on the ice. That it is their lives that have been committed to putting on a ferocious display of hockey skill night after night, since the time that they were young kids. That it is their careers that end after, on average, five and a half pro seasons, and that they have few marketable skills when that time comes, leaving most of them to try to live on whatever they made in their short careers.

The players, on the other hand, insist that people come to watch them. That it is their bodies on the line when they drop down to block a 100 mph slap-shot, that it is their careers that can be suddenly cut short by one errant elbow on the ice. That it is their lives that have been committed to putting on a ferocious display of hockey skill night after night, since the time that they were young kids. That it is their careers that end after, on average, five and a half pro seasons, and that they have few marketable skills when that time comes, leaving most of them to try to live on whatever they made in their short careers.

Sidney Crosby’s alienated labour

As a result, they feel that the NHL’s revenues ought to be split between them, the hundreds of personalities who bring us to our feet in exultation and amazement through the long winter months, not the owners in suits and ties whose greatest accomplishments tend to fall into the “I’m a successful businessman” category. I don’t spend my Saturday nights watching successful businessmen screw some sucker out of their money, I spend my Saturday nights watching Daniel and Henrik Sedin activate their magic twin powers and work a cycle until the defence go weak at the knees and the Canucks win again.

Indeed, there is a larger perspective to the NHLPA’s response to being potentially locked out for a third time in the last two decades by the owners’ collusion to impose a tighter salary cap, and it lies in the powerful reminder that these athletes’ labour power, like that of any other worker, is the property of the owners. For Sidney Crosby, a veritable Canadian icon, it must be rather unsettling to know that even he is alienated from the product of his labour;  Crosby produces spectacle, and lots of it, but the conditions under which he does so are controlled by someone else, and the profits that it generates largely accrue to someone else. Perhaps Sid the Kid can be forgiven for thinking that he had more say in how his labour gets used; as he says in a video message to the fans (pictured left): “As players, we want to play. But we also want what’s right and what’s fair.”

Crosby produces spectacle, and lots of it, but the conditions under which he does so are controlled by someone else, and the profits that it generates largely accrue to someone else. Perhaps Sid the Kid can be forgiven for thinking that he had more say in how his labour gets used; as he says in a video message to the fans (pictured left): “As players, we want to play. But we also want what’s right and what’s fair.”

But no, even in the high-flying world of professional sport, it is the owners who run the show. NHL team owners have historically been able to enforce the most arbitrary of measures and the players have to had to either submit to them or be kicked out of a profession in which they have spent years attaining a proficiency. Unquestionably, professional hockey players make salaries significantly higher than most workers, and the argument here is not that they are struggling to get by. But it is significant, all the same, that it is the players who create the NHL’s revenues – Winnipeg Jets’ owner Mark Chipman can’t sell Ondrej Pavelec jerseys to Winnipeggers without Ondrej Pavelec. And yet, while the players create the spectacle that sells tickets, jerseys and TV deals, the NHL owners expect them to settle for less than half of the profits they create.

The painful reminder that the business of hockey is not for us

It needs be added that the entire business of professional sport is an industry that has become so saturated in the capitalization of spectacle that it has become more or less completely alienated from the average fan who, increasingly, cannot afford to buy a ticket and watch his or her favourite team play live. Fans have become disconnected from the institution of hockey, and professional sport in general, and it from them. It is due to an unprecedented phase of commercialization of public spaces in the last twenty years that professional sport has become unaffordable and distant. It reeks of greed. Its politics — oft criticized here in the pages of Left Hook — glorify not the majestic drama of athletic competition, but a drunken, gambling, pugnacious, and sometimes-criminal masculinity epitomized by sports-talk television and radio.

Moreover, in this recent NHL labour dispute, popular media has again labelled these potentially locked out players as equally guilty of depriving us all of hockey as the owners. They — along with the owners — are presented as knaves, as ingrates violating some public trust, as men without principles, men who would be struggling at a ‘regular job’ but for the opportunity accorded to them by the joint venture that is the NHL.

Perhaps this is because we cannot relate to sports, particularly athletes, as anything other than genuinely different, functioning on some higher plane of human creativity and meaning, as opposed to workers in the factories where mass production for mass consumption is often the pattern. One must remember that professional hockey has been a business for some time, and this business abides in the world’s most commercialized societies. This appears to be an innocuous fact, yet so many are dismayed when commerce dominates this area, and athletes, their enormous salaries and endorsements notwithstanding, are considered as  employees. As the NHL owners’ commissioner Gary Bettman ‘turns his back’ on labour negotiations for the third time in his tenure, many hockey fans feel that he represents the worst of the hockey-as-a-business world. But the personalization of the problem on the character of Bettman himself may be a barrier to building a broader critique of the notion of a hockey industry itself.

employees. As the NHL owners’ commissioner Gary Bettman ‘turns his back’ on labour negotiations for the third time in his tenure, many hockey fans feel that he represents the worst of the hockey-as-a-business world. But the personalization of the problem on the character of Bettman himself may be a barrier to building a broader critique of the notion of a hockey industry itself.

Hockey is a commodity. That should be obvious. However, there is a prevalent notion that sport is so unique that it should be set apart from ordinary commodities like automobiles or cell phones. While the boundary between these two types of commodities is quite permeable, there has been a rather inconsistent basis for maintaining an analytic separation. Yet, continuously, the average irate fan and observer suppresses the important fact that hockey players (especially professional hockey players) have market power, but they do not control the enterprises responsible for the commercialization that has overwhelmed hockey in North America. One cannot deny that ultimate control in the NHL rests in the hands of those who employ the athlete: owners and mangers of sports franchises, leagues and media outlets.

Nonetheless, any critical analysis of this dynamic has been tempered by the near-obsession with consumer sovereignty, with people’s identities and even ‘rights’ as consumers. As hockey has increasingly become commercialized, any substantive debate about ‘the game,’ or the role of sport within the community has been deflected by a wide variety of frustrations that don’t have much to do with the actual labour conflict at hand. The commercialization of hockey has enriched some athletes, but has smiled most favourably on owners, agents, promoters, sponsors and the other industries that capitalize on the spectacle. Fans and media commentators recognize and resent the former but tune out the latter. For them, it is the wheeling and dealing of both players and owners that have profaned the sanctity of hockey.

What seems to be at issue for the fans is a presumably final assault on the romantic ideal that sport is, or at least should be, different from other commodities that are produced for exchange in the market. Behind this seems to be a disgust with the notion that some areas of life can be contaminated by the logic of profit and economic growth and the instrumental rationality that follows. “It is the fans who are being punished,” goes the cry, and this is certainly the part of the story that resonates most powerfully with most of us, since most of us are ‘the fans.’

Radical and less-radical conceptions of a better world (of sport)

This repugnance at the idea of business contaminating the otherwise ‘pure’ sphere of cultural life stands as a significant ideological counterpoint to current trends in Canadian consumer cultures, and one that perhaps ought to be celebrated. Indeed, this time around, the lockout is generating stronger criticism of the notion of hockey-as-business and team owners greed than in the past. (Sam Donnellon’s editorial in the Toronto Star is a clear-headed and worthy example.) But rarely does this critique surface in any conscious way as broader public criticism of major league sport and the industry of pro sports. Popular criticism of the industry is almost never viewed as overtly ‘political’ and is rarely extended to encompass a broader critique of current patterns of economic accumulation and the corporate and state polices that sustain them.

Instead, they are much more likely to be draped in nostalgia and blended with the language of individualized consumer revolt. Today’s apparent greed and corruption are contrasted to the ‘good old days,’ a mythical time when owners were sports people first and entrepreneurs second, and when professional franchises were more deeply anchored in their home communities, and players were simply happy just to play the game. Yet this emphasis on the rights and needs of individual consumers is, itself, part of the economic and ideological conditions that is promoting the current trends and conflicts in the sports industry.

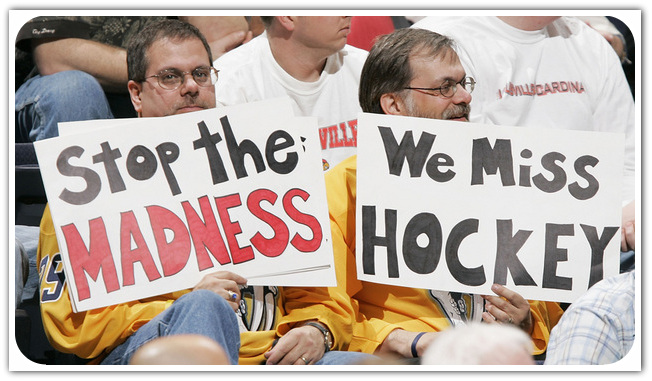

‘Stop the madness,’ indeed. Popular conceptions of the ‘good old days’ typically celebrate the major leagues and their ‘traditions.’ But the popular construction of tradition here tends to be  highly selective (ignoring, for instance, the racial apartheid that characterized many professional leagues for huge swaths of the 20th century) and the tinted images usually tell us little about the changing political-economic pressures and limits that permitted development of sports cartels and about their role in the constitution of national and continental popular cultures. In the absence of an adequate historical and political-economic analysis, it is difficult to discern what is new about the current NHL lockout and what is primarily an extension of older economic and cultural patterns and tendencies. It is even harder to conceive of how sport might serve as an additional organizing point for resistance to the broader pressures and limits shaping life.

highly selective (ignoring, for instance, the racial apartheid that characterized many professional leagues for huge swaths of the 20th century) and the tinted images usually tell us little about the changing political-economic pressures and limits that permitted development of sports cartels and about their role in the constitution of national and continental popular cultures. In the absence of an adequate historical and political-economic analysis, it is difficult to discern what is new about the current NHL lockout and what is primarily an extension of older economic and cultural patterns and tendencies. It is even harder to conceive of how sport might serve as an additional organizing point for resistance to the broader pressures and limits shaping life.

Professional hockey players can be criticized for many failings, even for their alleged lust for higher and higher salaries, but in a society dominated by commerce and economics, it seems churlish to chide them because they accept a high salary for the randomness of their athletic ability and an all but insatiable demand by the fans for professional sporting events. Sports markets in the world’s most commercial economies are less than perfectly competitive. Governments permit leagues and professional sports teams to operate outside the anti-trust statutes and accord them excessive tax breaks.

Sports fans who think that professional sports like hockey have become contaminated can and should press governments to apply fully and rigorously the anti-trust statutes and civic responsibilities to all professional sports. Full implementation of the anti-trust laws would eliminate barriers to entry and increase the number of teams and contests and the enforcement of corporate civic responsibilities would return tax dollars to important — if not crucial — local social programs.

A more radical proposition would be to remove profit from sport altogether. Since sport is in many ways a fundamental part of culture, and communities contribute excessively to the development of the athletes and facilities that pro-leagues exploit, sport should be the property of the community. Organizations structured along non-profit and revenue sharing lines would go a long way to repatriate and reinvigorate sports at all levels and among and across genders. Government policies of building and creating public sporting facilities around the country would revive physical education and personal well-being. Such a scheme would demand a serious evaluation of capitalist ideology, not only in relation to sport, but in relation to economic and political power. Something that we all know is very much needed today.

Julian Ammirante enjoys every sandwich and maintains a healthy obsession with Italian and South American football. Tyler Shipley teaches at York University and is the editor of Left Hook journal, where this piece first appeared.