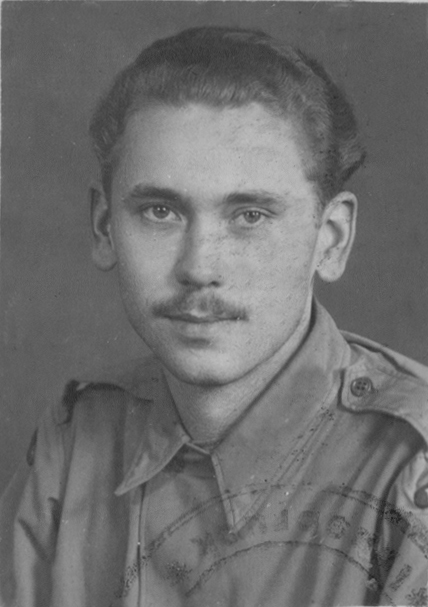

Today I remember my father, Mieczyslaw Majka, who as a young man fought in the Polish Army when the Nazis invaded his country in 1939. His job was to sit in a reconnaissance tower noting the position of incoming bomber flights and radio the information to anti-aircraft batteries. As a child I was shaken by his description of sitting high above the ground while bombs exploded all around him. Some 50,000 of his colleagues fell during the four weeks that launched World War II before Poland surrendered.

When the Polish army was defeated he joined the underground, fighting for the duration of the war in the Armia Krajowa (AK) in a cell responsible for smuggling weapons into the country. At the time, simply possessing a gun was an immediate death sentence from the Nazi authorities. It was a harrowing five years, and in the spring of 1945 he had to flee the advancing Soviet army who arrested all the AK members (a pro-western organization unsympathetic to Bolshevism) sending them for “rehabilitation” to the Gulag — an excursion from which few returned. He was the only member of his cell to escape.

Fleeing to the west across the Czech-German border he was arrested by American forces who — unable to distinguish friend from foe — came within a hair’s breadth of handing him over to the Russians, which almost certainly would have lead to a summary execution. The result of his patriotic activities was exile from the country of his birth for the rest of his life. And he was one of the very lucky ones.

Fleeing to the west across the Czech-German border he was arrested by American forces who — unable to distinguish friend from foe — came within a hair’s breadth of handing him over to the Russians, which almost certainly would have lead to a summary execution. The result of his patriotic activities was exile from the country of his birth for the rest of his life. And he was one of the very lucky ones.

Over 6 million of his countrymen and women died during the Second World War. My great uncle was one of the 22,000 Polish officers executed in the Katyn Forest in April 1940 by Lavrentiy Beria’s NKVD on the orders of Stalin, Molotov, Voroshilov, and Mikoyan. As a student in Moscow in 1979 I could occasionally see Vyacheslav Molotov strolling the embankment of the Moscow River, an unrepentant Stalinist, uncaring and oblivious to the suffering he had caused. War is a bitterly cruel taskmaster that spares few that fall within its ambit.

My father died on this day, Remembrance Day, November 11, 2007.

There is, of course, courage and valour, patriotism and principle, along this pathway. People who give of themselves to protect others and the core values they believe, in the face of something much worse. Whether by choice or necessity, of standing against forces that seek to demean and degrade that and those that we love and value. A profoundly intolerable situation.

But at the same time, it also illuminates a profound failure. A failure of society — and most importantly its leaders — to recognize the fundamental humanity of everyone, the sanctity of the earth that gives birth to all, and the desire of all sentient beings for life and an environment and milieu that supports them.

It’s an old adage that we must develop better ways of resolving conflicts and inculcating moral precepts to present and future generations, and to do so we need — each and everyone — to resist those tendencies that attempt to cajole us into believing that peace is to be achieved by investing in the implements of war. The warships, the F-35 fighter jets, the unmanned drones, the land mines, the cluster bombs, the napalm, the nuclear warheads. The coins of the merchants of death. We must demand this of our leaders: that those who represent us, who provide leadership of our society and economy, reflect the values of life and peace, not war and death.

It’s an old adage that we must develop better ways of resolving conflicts and inculcating moral precepts to present and future generations, and to do so we need — each and everyone — to resist those tendencies that attempt to cajole us into believing that peace is to be achieved by investing in the implements of war. The warships, the F-35 fighter jets, the unmanned drones, the land mines, the cluster bombs, the napalm, the nuclear warheads. The coins of the merchants of death. We must demand this of our leaders: that those who represent us, who provide leadership of our society and economy, reflect the values of life and peace, not war and death.

We can best honour and remember those who have traveled this pathway in our stead by actively working to make sure that no one else has to walk in their steps. To remember, on this day and on all others, those who are dying daily in conflicts in Syria and Tibet, in Afghanistan and Sudan, in Somalia and Iraq. To do our utmost to stop the wars. To ensure that our leaders conduct themselves on the basis of moral and ethical principles that reflect human values and not mercantile ones.

Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, Francisco Franco, Joseph Stalin, Idi Amin, Pol Pot, Augusto Pinochet, Radovan Karadzic, Muamar Gaddafi … all these tyrants have come and gone leaving tens millions of dead — and even more ruptured lives — in their wake. Bashar al-Assad will eventually go as well. But their like will continue to appear: sad men twisted by hate, jealousy, greed, inadequacy, vindictiveness, and other soul-distorting forces. Fostering hate is much easier than love. When conjured from the shadows, fear can trump all other emotions, intolerance all other values.

Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, Francisco Franco, Joseph Stalin, Idi Amin, Pol Pot, Augusto Pinochet, Radovan Karadzic, Muamar Gaddafi … all these tyrants have come and gone leaving tens millions of dead — and even more ruptured lives — in their wake. Bashar al-Assad will eventually go as well. But their like will continue to appear: sad men twisted by hate, jealousy, greed, inadequacy, vindictiveness, and other soul-distorting forces. Fostering hate is much easier than love. When conjured from the shadows, fear can trump all other emotions, intolerance all other values.

In sharing in the remembrance of my father, and of all the men and women who have traveled this path before and with him, and all those presently on this journey, remember this: we must all summon our better angels to stop the violence perpetrated on one another and upon the planet that is our home. Peaceful, constructive actions are the best way we can honour their legacy, lives, losses, suffering, and humanity. We must never forget the past, but in the here and now, we must also pay it forward to the next generation. Let us throw the torch to them not from failing hands. Let there be no more quarrels with the foe, nor foes. Let the fields in Flanders, and everywhere else, grow flowers, not crosses.

Christopher Majka is an ecologist, environmentalist, policy analyst, and writer. He has a Russian Studies degree from Dalhousie University and the Pushkin Institute in Moscow. He is the director of Natural History Resources and Democracy: Vox Populi.