You can change the labour conversation. Chip in to rabble’s donation drive today!

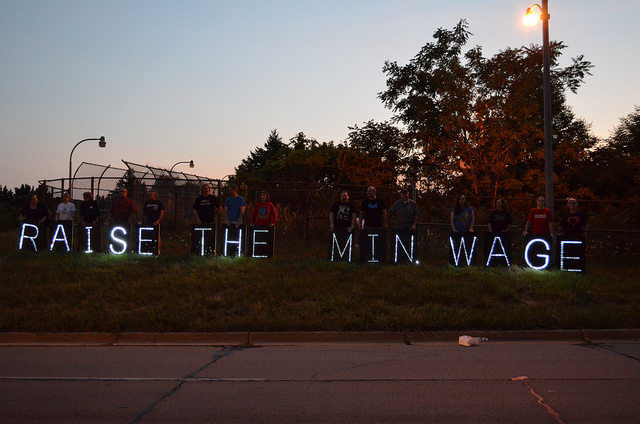

The demands to substantially increase the minimum wage are growing louder south of the border. Workers across the most poorly paid industries are finding creative ways to raise the issue with strikes by fast-food workers and Walmart employees making waves across the country. What’s more, many of these workers are boldly arguing not for incremental increases but a substantial boost: a $15 per hour minimum wage has been one of their slogans. Even some elected officials have taken up the $15 per hour cause. Support for a more modest minimum wage increase is at over three-quarters among the general population and the issue could become an important one in the U.S. 2014 elections.

Although Canada has not seen the kind of energized and far-reaching calls and protest movements for raising the minimum wage, the working poor in this country face similar difficulties. Anti-poverty groups and unions in this country have long argued for higher minimum wages. Many have extended their demand to include not just a higher minimum wage, but a living wage.

Yet despite the renewed focus on for higher minimum wages, there are many who continue to argue that higher minimum wages are not only ineffective but actually do more harm than good for the very working poor they aim to help. Even as economists and activists in the U.S. continue to accumulate data that shows this to be simply untrue, experts on Canada’s right have an easy answer: N/A. Not applicable; Canada is special. An article in Maclean’s magazine by Stephen Gordon neatly summarizes this line of argument. I want to take a look its claims and show that they that do not apply. Indeed, Canada has much to learn from the current U.S. surge in academic, popular and activist support for raising the minimum wage.

Gordon makes two arguments: minimum wage hikes lead to lower employment and do not affect poverty rates. The first claim is an old trope; it has been largely put to rest in the U.S., but remains popular among Canadian critics of minimum wage hikes. One of the main objections to the use of U.S. minimum wage studies in a Canadian context is that many U.S. studies only look at the federally mandated minimum wage. Since provinces set minimum wages in Canada, critics like Gordon claim that Canadian studies can be more nuanced, looking changes across time and jurisdictions that cannot be captured by U.S. studies.

Debunking this claim requires a brief foray into the arcane world of statistics and economic method. Recent improvements in methodology and the increased availability of county-level data have led to much more realistic and robust models. Although earlier studies had looked at what happens in neighbouring counties along state lines when the minimum wage increases in only one of the two states, these new studies took the approach a step further. They repeated such county-level tests thousands of times, taking into account a broad range of state- and location-specific trends that impact on economic and labour market properties, such as the percentage of low-skill work and so on. All such methods allow economists to isolate the effects of minimum wage increases on changes in employment and account for many potential biases and confounding factors.

A review of such studies published in 2013 (with the studies reviewed all carried out since the year 2000) found that there is no statistically significant link between employment and minimum wage increases. The authors compiled results from six different methods and four data sets to find that minimum wages do not lead to falls in employment. A second, very recent review corroborates these results.

Furthermore, both reviews found that higher minimum wages not only aren’t responsible for raising unemployment, they actually have a range of other positive economic effects. These improvements include, of course, higher incomes, but also less employee turnover, less wage inequality and better organizational efficiency.

The Canadian studies cited by Gordon and other Canadian critics of minimum wage increases are not as sophisticated. While the new U.S. studies use a fine sieve to capture the unbiased effects of a minimum wage change and nothing else on employment, the Canadian studies use the equivalent of a large cauldron. Data from across Canada is lumped together with few statistical controls that do not adequately capture the complexities of structural differences between labour markets and economies in different provinces. This allows the oft-cited disemployment effects to be found — for example, that a 10 per cent minimum wage hike is associated with a 3-5 per cent drop in teen employment. The other piece of economic evidence that is often paraded out is a review that looked at studies across the world and also found disemployment effects from minimum wage hikes. Its results, however, do not take into account the newer, more sophisticated research and are based on the review authors’ subjective appraisal of research quality.

The second criticism made by Gordon is that minimum wages increases do not alleviate poverty and inequality. Luckily, significant recent research has focused on the relationship between minimum wages and poverty — and found the exact opposite to be the case.

A newly released study on the links between minimum wage increases and poverty reduction by University of Massachusetts-Amherst economist Arindrajit Dube is one of the most comprehensive on the question yet. Dube carries out both a meta-analysis of previous studies and combines these with his own statistical findings. Both show a strong positive link between higher minimum wages and lower poverty rates.

All but one of the 12 major studies that Dube examines find that raising the minimum wage decreases the poverty rate and the one study that finds the opposite effect uses a problematic method to obtain its results. Combining and averaging the results of the 11 studies shows that a 10 per cent increase in the minimum wage will decrease poverty rates by 2 per cent (note, however, that this is not a decrease of 2 per cent, i.e. from a rate of 12 per cent to 10 per cent). In his own model that includes even more controls to eliminate bias from other factors, Dube finds a 2.4 per cent decrease in poverty rates from a 10 per cent minimum wage hike, which rises to 3.6 per cent if some passage of time between the wage increase and the poverty decrease is factored in. Again, older models that ignored some of these time lags and broader economic trends that could bias data found lesser effects. Furthermore, minimum wage increases would help alleviate income inequality with gains going disproportionately to lower income brackets. Very concretely, Dube estimates that the possible 39 per cent increase in the U.S. federal minimum wage (from $7.25 to $10.10 per hour) would lift 4.6 million non-elderly Americans out of poverty in the immediate short term and 6.8 million under a longer time horizon.

Although the above data all come from the U.S., the characteristics of minimum wage workers in Canada are quite similar to those found in our neighbour to the south. Here again, the myth of Canadian exceptionalism fails. Contrary to another myth, minimum wage workers are not all teenagers from rich families. Minimum wage earners make up about 6 per cent of all Canadian workers (5 per cent in the U.S.) and 40 per cent of them are over 25 (50 per cent in the U.S.). Minimum wage workers are also disproportionately women, immigrants and come from other marginalized communities; they are more likely to work in insecure, part-time jobs, primarily in the service sector. In addition, data for Ontario shows that of workers making just above minimum wage (between $10.25 and $14.25) compromise another close to 20 per cent of employees in that province, and 61 per cent of them are over 25.

Adults who are either minimum wage earners or not far from it form a significant group; many of them are living below, at or just above the poverty line. Indeed, 25 per cent of all low-income Canadians under 65 live in household that relies on a working poor individual to be the main breadwinner. These households and others would be directly helped by minimum wage increases. Whether the proportions would be exactly the same as those calculated by Dube for the U.S. is open to debate — what is not is the effect of minimum wage increases on reducing poverty.

This new data is quite different from studies quoted by Gordon, which purport to show either a lack of change or an increase in poverty rates after a raise in the minimum wage. To do so they use outdated methodology or speculative simulations, which further erroneously assume that employment falls due to minimum wage increases. One study also argues that minimum wage increases will contribute to greater inequality — another questionable finding given the results of Dube’s poverty rate studies and the evidence for wage compression found in the new employment studies (some previous related thoughts of mine on this topic here.

Stephen Gordon ends his attempt to discredit minimum wage increases with thoughts on other poverty-fighting measures. On at least one important count he is right: other measures such as the Working Income Tax Benefit are indeed a good way of helping the working poor. Only, contrary to Gordon’s suggestion that increasing such benefits be used as a substitute for raising the minimum wage, the two policies are actually complements.

The minimum wage may be an effective if “blunt” poverty-reduction tool if it used in isolation; it is best used as part of a comprehensive anti-poverty strategy that also includes more progressive taxation, better public services and income supplements (potentially all the way to a Guaranteed Basic Income ). A higher minimum wage is a key component of such a strategy as it provides not only higher incomes but a host of other side benefits — for example, increased voice and bargaining power for workers and increased independence for women, recent immigrants and other economically vulnerable groups (who are disproportionately represented amongst minimum-wage earners). Broader economic and political change is the key to decreasing inequality and eliminating poverty; raising the minimum wage is one fast, effective and fairly easy-to-implement step on that long road.

So there we have it. Not only do minimum wage increases have real impacts in the lives of their intended working poor recipients while not cutting into employment, Canada is also not a freak of economic nature where these results do not apply. Although the U.S. has long been a leader in showing the world how to increase inequality and poverty, a new generation of workers, activists, scholars and — yes — even politicians has gotten behind the idea of higher minimum wage as a means to roll back some of that poverty and inequality. Some of the most vulnerable American workers have stood up, spoken out and led the charge. Time for all of us in Canada to follow suit.

Like this article? Chip in to keep stories like these coming!

Michal Rozworski is an independent economist, writer and organizer. He currently lives on unceded Coast Salish land in Vancouver, B.C. He blogs at politicalehconomy.wordpress.com and you can find him on Twitter @MichalRozworski.

Photo: Wisconsin Jobs Now/flickr