In the early part of 2013 my partner Natalie and I and our three children were evicted from the apartment we had lived in in west end Toronto and that was our home. It was well suited for us, with three bedrooms, a deck and being very close to both our work and the school all our kids were enrolled in.

We had done nothing wrong. The building had changed hands, and the new owners claimed that they intended to live in the apartment, which was above a store where they supposedly planned to open a business. This is their right under the law, regardless of how long a tenant has lived there, or the tenant’s circumstances. The owner at the time, our landlord, issued us an eviction notice so that the apartment would be vacant on the closing of the real estate deal.

We did not contest the eviction. There really would have been no point. Instead we went through the process, an always stressful and costly one, of finding a new home, packing up all our things and moving.

This could have been the end of the story, but, instead, only a couple of months after moving we noticed a “For Rent” sign in the window of our former apartment. The new owners, obviously, had not moved in! With a little sleuthing we found out that they were renting it out, and had upped the rent by $300 a month, something that is legal on vacant apartments under our Mike Harris era Ontario “rent control” laws. This allowance obviously provides an incentive for new owners to evict existing tenants claiming that they or a family member intend to move in so as to jack up the rent on an apartment they think they can get more for. Otherwise, with tenants who are already in place they can only increase rent according to a regulated guideline, this year at only 0.8 per cent.

This is a provision that clearly should be changed and full rent controls should be put back in place on vacant apartments as well.

It was the previous owner who had evicted us, so we took the numbered company (with lots of helpful advice from a friend involved with the Federation of Metro Tenants’ Associations) that had been our landlord to the Landlord Tenant Board for having evicted us in bad faith. If proven, a tenant is allowed to claim for all moving expenses and can claim for any difference in rent for every month of one year if the new apartment they have moved into is more expensive. In our case, for example, the difference in rent was $100 a month more for our new apartment, so we were able to try to claim for $1,200 in damages. ($100 x 12 months).

This is done by filling out a T5 “Landlord Gave a Notice of Termination in Bad Faith” form. This can be found on the Landlord and Tenant Board website along with the relatively easy steps for how to go about filing it. You will have to have documentation for all claims, like rent receipts/lease agreements, receipts for movers/moving trucks, evidence that they are renting it (we had a photo of the “For Rent” sign in the window), etc. If you are ever evicted for this reason, hold on to these and any screengrabs or newspaper ads, etc.

We and our former landlord received a hearing date notification from the Board and then argued our cases at the hearing itself. You can have a lawyer represent you, but this is expensive and in most cases like this, simply not worth it. Obviously if you can have a lawyer or experienced paralegal do it this is always advisable. We represented ourselves. Be aware that your former landlord is not only allowed (as they should be) to be present at the hearing, but that they can ask you questions. If you are not prepared or willing to have this happen, and it can, of course, be stressful, then you cannot pursue them. On the positive side, the adjudicator at the hearing will not tolerate interruptions, angry attacks or insults, so you need not worry about these.

A month or so after the hearing we received the verdict. We had won! We had been awarded the $1,200, plus moving expenses, plus some damages we had not even requested. It was an across-the-board victory and vindication. The Board Order was mailed to both us as tenants and the landlord. They were given a specific date to pay by, and told that the decision was final and binding (it is only in very rare cases that a Board judgment can be appealed).

The payment date came and went. Eventually they sent a small fraction of what we were owed and made it clear that this was all they intended to pay.

And nothing, at all, happened.

This is when you discover that in Ontario, there is absolutely no enforcement arm for Board decisions. The landlord or tenant is ultimately responsible for enforcement. While landlords have obvious ways to enforce a judgment, as the tenant still lives in the apartment and as eviction notices, for example, can be enforced by the Sherriff, a tenant, especially a former one, cannot do this. You have to find a way to collect the judgment yourself, and this is not easy to do.

The Landlord Tenant Board has a “help” line and when we called it after the landlord refused to pay, we were politely told that there was nothing they could do. On three separate occasions I was told personally that I was “wasting my time,” that pursuing the landlord would cost more money than it was worth, that I should likely hire a collection agency to pursue them and, as one helpline worker told me, “hope for the best.”

Hiring a collection agency is an option. For a percentage of your judgment they will attempt to collect it and, if it is high enough (they can be up to $25,000), they might even pursue it in court for you. If you have no time to pursue it yourself, this may be the best option. Our judgment was for under $2,000 total however, as many will be, and a collection agency is unlikely to pursue this in court. They may succeed in harassing your former landlord into submission, and they do not get paid unless they do, but a landlord can simply ignore them and wait them out.

Alternately, of course, if you have access to a lawyer or paralegal and if it is either pro bono for you or worth it to pay the fees, then you should take advantage of this and have them take action on your behalf. This is, when possible, always the best course of action.

But it is not always possible, and Natalie and I certainly could not afford this, and even if we had been able to, it would not have been worth it for a judgment that size.

After a considerable amount of digging around, and again with the helps of friends, I found that there is another option. What you have to do is have the Board Order converted to a judgment in Small Claims Court. First, send your landlord a letter telling them that they have failed to make restitution as required, and tell them that if they do not pay within 14 days you will take further action. I have posted a copy of the one I sent (with some information redacted) here.

Assuming they do not pay, you need to take the Order to the Small Claims Court office in your community in Ontario and do this in person. In Toronto this is located at 47 Sheppard Ave. E. A full list of office addresses can be found on the website of the Ministry of the Attorney General.

This will cost you $100, but you can claim this as a cost later and recoup it from your landlord when and if you succeed in getting what you are owed. You need to go with identification and proof of address. The key thing that you also need, if you wish to be able to proceed to immediate garnishment and enforcement of the decision, is your landlord’s banking information. Usually you will need to get a cancelled rent cheque that has been cashed by your landlord from your bank. This will have your landlord’s bank’s stamp on it, which contains the banking information (bank, account number, branch number, etc.).

If you do not have or are not able to get your landlord’s banking information it becomes far more complicated as you will have to serve forms to have a hearing held to compel your landlord to provide the information for garnishment or you will be required to, if they have one, compel their employer to enforce the judgment by garnishing their wages (if you had or have a numbered company landlord, this can obviously not be done). Otherwise, you have to seek other types of property seizure/liens that are very difficult to pursue.

Assuming you do have or can get this banking information, and it is generally not that hard to obtain, you will need to fill out and file at the Small Claims Court office a Form 20E “Notice of Garnishment” along with a Form 20P “Affidavit for Enforcement Request” with a clerk at the court office. These forms can be found at the government website along with instructions for their completion. The clerk will stamp the notices.

You want to claim for your full Board order amount, plus the $100 cost of the judgment conversion, plus any interest available to you for late payment. The interest you can claim and from what date you can apply it will be included in the original Board order.

You will then have to serve the stamped Notice of Garnishment on the financial institution where they have their account and on your landlord. You also have to send your landlord a copy of the 20P form. It is critical to note that you do not have to serve your landlord until 5 days after you have served their bank. This prevents them from removing the money from the account. While other methods are allowed, and are detailed in the form instructions, I advise serving the documents via registered mail to have a paper trail.

When you serve the stamped 20E Notice of Garnishment on your landlord’s bank you also have to include a blank “Garnishee’s Statement Form,” form 20F, that they will send to you filled out when they have either enforced your garnishment or are attempting to claim that they cannot do so.

Once you have served the bank and your landlord, you will have to complete and return to the court, very promptly, a form 8A “Affidavit of Service.” This must be, as the form says, “signed in front of a lawyer, justice of the peace, notary public or commissioner for taking affidavits,” meaning that you will have take it to a lawyer’s office and have this done, generally for a fee of around $20, (and then mail it to the Small Claims Court) or to take it back to the court office and do it there. It is critical that you take this step, or you will not get your garnishment.

Small Claims Court offices have free legal clinics available to people of lower or medium income (and I suspect anyone doing this on their own is almost certain to qualify) who will give you advice and even fill out the forms for you. Take advantage of this. I would have had a much harder time without them. The forms are confusing if you are not familiar with them, and they have to be filled out properly or they are not valid.

Expect, especially in major centres, to spend a long time at the court office. If at all possible, go as early as you can in the day.

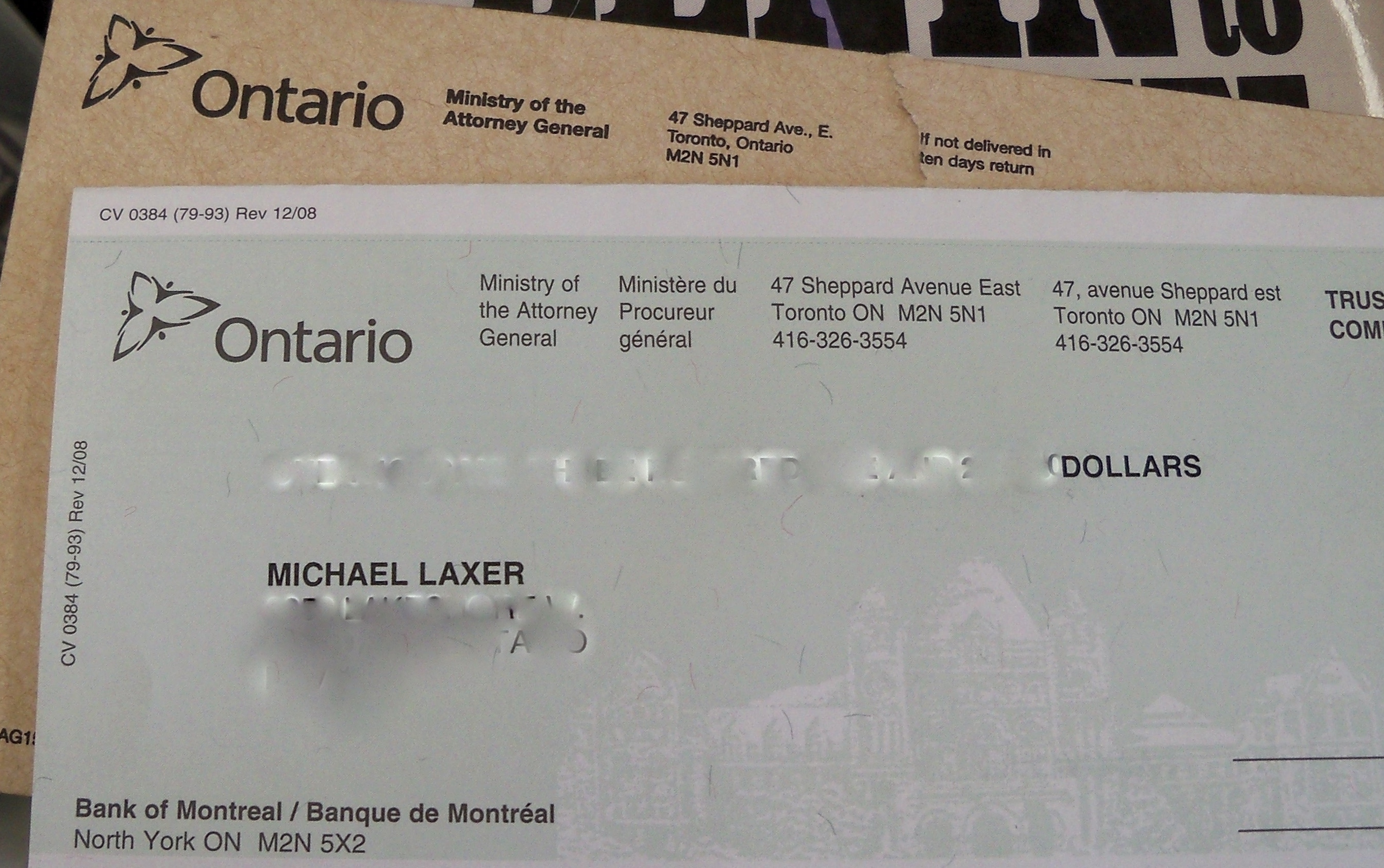

If you follow these steps, and if your landlord has the money in their account, the bank will garnish it, will send it to the Ministry of the Attorney General, and, barring a very unlikely appeal of this, you will be issued a cheque within 30 days of the ministry getting the money (which generally happens within 20 days of you serving the bank.)

We finally got our cheque, and restitution, in early January 2014. While this was a very satisfying moment, it took months and many hours of effort. If I were not self-employed and, to be honest, driven by a sense that my family and I had been wronged, I probably would have just given up. If reading the steps involved seemed a frustrating and tedious effort, this is what the actuality of it is like! I can honestly say that had I known the effort involved, I am not sure I would have done it.

This is wrong. The fact that it is so difficult for tenants to get the restitution and justice that they are due after a Board order is simply wrong. The power relations and resources of landlords and tenants, in the overwhelming majority of cases, are not the same. Landlords in the vast majority of cases have far greater resources and far more that they can do to evade compliance with an order.

Ontario needs to implement an enforcement arm for the Board in conjunction with both landlord registration and landlord licensing. Landlords should be required to adhere to the various codes and acts, including the many appalling cases of lack of maintenance, or face losing the privilege to be landlords. There should be direct consequences for slumlords, including provincial and municipal legislation allowing the expropriation of their property and its conversion to public or co-operative housing. All landlords should be made to place their banking information on file with the government so that in the event a tenant gets a judgment, they can act on it without all of these hurdles.

This is a basic issue of fairness. It is simply unfair to expect tenants to do what is now required to get the money they are owed from what are often wealthy individuals or corporations. These are judgments made by government boards in the interest of social justice and the enforcement of government enacted regulations and laws. The reality that the government then leaves it to the tenant to enforce the order entirely on their own is a real injustice.

It is very clear that the vast majority will not be able to do so. This makes one wonder if that is, in fact, the government’s intent.

This article outlines the specific case and steps that Natalie and I had to take. Every case, of course, is somewhat unique. If you can, you should always try to get the help of a lawyer or paralegal if this is possible for you. For further help and advice, please also check out these organizations:

The Federation of Metro Tenants’ Associations

Community Legal Education Ontario

Law Help Ontario (a program of Pro Bono Law Ontario (www.pblo.org), a registered charity with a mandate to increase access to justice for low-income Ontarians)