This blog is the second in CCPA-NS series called “Progressive Voices on Public Education in Nova Scotia.”

The Minister’s Panel on Education has challenged Nova Scotians to “get involved” and help “effect change in the education system.” Public schools are among our most important democratic institutions, so the call for public input is a welcome one. If the Minister’s panel really wants to effect positive change in Nova Scotia’s public schools, it’s worth paying serious attention to what is and isn’t working in other contexts.

Efforts to reform education in the United States provide a number of examples of what not to do. Since the 1980s, policy-makers have looked at U.S. schools, especially those in urban areas, and seen an educational system in crisis. Although this view is contested, a coalition of education “reformers” has spent the past 25 years promoting changes to education policy that emphasize three broad pillars: choice, increased standards and accountability.

First, reformers advocate giving parents more choice in where they can send their children to school. School choice policies have led to an expansion of charter schools, which are publicly funded, but privately managed, and voucher programs, which give parents a tax credit toward tuition at a private or religious school. In principle, this competition would improve public education by forcing poorly performing schools to improve or face closure, while rewarding successful schools with more students and funding.

Second, reformers support increasing academic standards and assessing how students meet those standards through standardized testing. The 2001 No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act required all states to conduct a series of tests in reading, math, and science beginning in Grade 3 and used these tests to determine whether schools were making “adequate yearly progress” (AYP) toward universal student “proficiency.” Currently, the Obama administration has been strongly advocating for states to adopt a common set of rigorous standards known as the “Common Core.” These too would be assessed by standardized tests.

The third pillar of education reform is to hold teachers and schools accountable for student performance on standardized tests. Accountability for schools was enshrined in NCLB, which tied certain federal funds to improvement on test scores and also allowed students to transfer out of schools that did not make sufficient progress towards proficiency. More recently, state legislatures have begun to link teacher tenure and pay increases to student performance on tests. In some states, individual schools and entire districts have been taken over by the state because of poor testing performance.

Choice. Standards. Accountability. These seem like common sense pillars of education policy. The results suggest otherwise.

Take “choice.” Charter schools have actually had mixed academic results. Some charter schools are excellent, but on average they perform no better, or even worse, than traditional public schools. Most charter schools limit their enrollment and are less likely to enroll students with special needs and English language learners. Further, charter schools rarely offer transportation. Although they are not a viable choice for many students, the shift in state funding to charters leaves traditional public schools with fewer resources to teach a more challenging student body. To top it off, charter schools have faced serious scrutiny over their waste and misuse of public funding. The fact that charter schools are primarily authorized in urban areas with predominantly black and Latino student populations raises serious concerns about whether “school choice” policies are actually contributing to racial inequality in America’s public schools.

What about increased academic standards and assessments? We all want students to receive a rigorous education in all subjects; however, current policies focus intensely on assessing language arts and math. Schools focus more resources on these tested subjects, while the opportunities to develop rigorous curricula in non-tested subjects, like art and music, world languages, history, civics, and science fall by the wayside. This is especially true for students of colour. Second, there is less classroom time spent on instruction and more time devoted to prepping for and taking tests. Third, there are serious concerns that increased academic standards are developmentally inappropriate for young children.

Finally, what about accountability? In a democracy, the public has every right to demand that our schools are performing well. In doing so, it’s important to use the appropriate data and to hold teachers and schools accountable for what is in their control. Here, again, American education reform policies miss the mark. Not only does research show that a student’s socioeconomic status is a better predictor of academic performance than test scores, new studies also suggest that tests are not accurate predictors of “good teaching.”

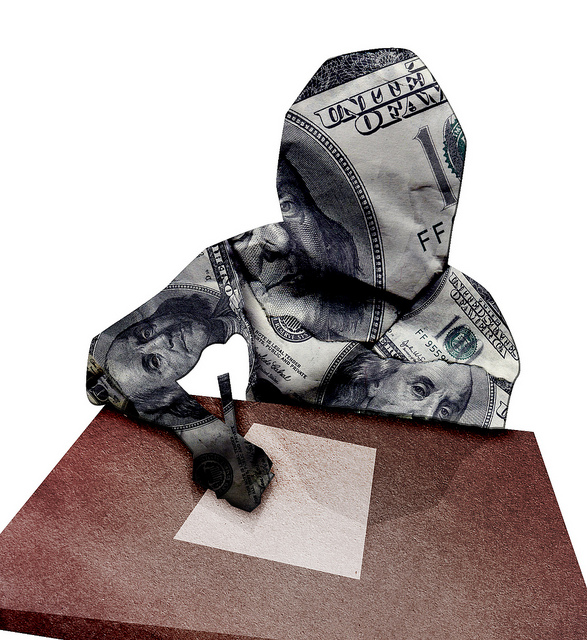

In the search for solutions to America’s poor performing schools, policy-makers have listened to philanthropists, wealthy political donors, and non-profit organizations like Teach for America. At the same time, they have ignored the voices of educators themselves, who can speak directly to the challenges facing urban students, the effects of reform, or what students really need to succeed.

As the Minister’s Panel on Education reviews Nova Scotia’s public education system, what lessons should they take from 25 years of education reform in the U.S.?

First and foremost, don’t look for silver bullet solutions, even when pitched as common sense ideas like “choice,” “standards,” and “accountability.” Instead, start by asking what the purpose of public education is. If the answer is to foster critical thinking, lifelong learning, and the skills to participate in our democracy as citizens as well as workers, then watch out for policies that narrow the curriculum (see the first blog post in the series) and cut access to libraries and the arts.

Next, seek out input from educators, at all levels and all school boards, about what students need (in order) to learn.

Finally, remember that many of the factors that contribute to academic success are outside the purview of schools themselves. Ensuring a quality education for all Nova Scotian students, especially those from marginalized and vulnerable communities, requires a strong commitment to policies that foster social justice and economic equality in all areas of life.

Dr. Rachel Brickner is an Associate Professor in the Department of Politics at Acadia University. She is a Research Associate of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives-NS and serves on its Research Advisory Committee.

Image: Jared Rodriguez / Truthout