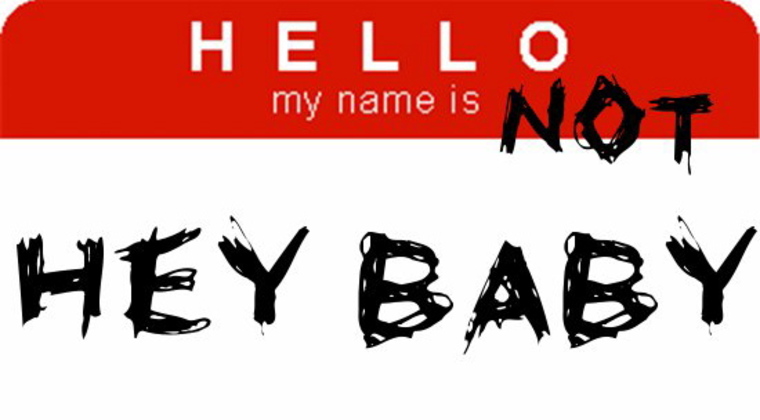

They’re baaaack! Guys who hassle women on the street, who believe they have the right to tell any woman they see what to do, from “Smile, sweetheart!” to “Don’t eat that, you’re fat enough already!”

That kind of behaviour is so 40 years ago! I should know. I was there, and fought the behaviour, and thought we’d made some lasting changes. Guess again.

Now that the Third Wave of feminism is encountering some familiar problems, I thought I’d look back at some of the columns I wrote in the 1970s and 1980s during the Second Wave. One of my more popular Homemaker’s columns was about popular (i.e., male) expectations of women as “nice ladies.”

I argued that, to a certain 1970s Peter Pan culture, women were individually invisible, interchangeable, expendable and accountable to any male who happens to be handy for every action or purchase. Only rules like these would account for the behaviours I saw in so many guys around me.

In 2014, though, I’d like to talk about what women have every right to want and expect other human beings to recognize when they are navigating shared space — on the sidewalk, in the food court, in the classroom or worship space, and certainly in the workplace. These points may seem glaringly obvious, to women at least, but apparently some men (especially conservative legislators) need reminders.

1. Even when a woman is in public, her body is her own private space, not public property.

What she eats, what she wears, what she buys, is her own business. So is her decision whether to breastfeed, and when. In the West, men who indulge in street catcalls or random lectures of women they don’t know are only exhibiting their own inability to control themselves, not any power they have over women.

2. A woman’s sexuality and reproduction are her own to control.

In fact, every person’s sexuality is their basic human right, whatever it is, so long as they don’t harm other beings. Similarly, a society that allows sex or parenting to be punishment will reap a whirlwind of angry, violent people. Again, male legislators only signal their own impotence with their repeated attempts to intervene in women’s control of their bodies. Ask the Vatican what their baptized Catholics are willing to give up first: contraception, or the Church. (Although, so long as sex is unmentionable, I guess nobody really knows.)

3. Women’s work is at least equal to men’s.

The overwhelming majority of women have always more than earned our keep, even though most of our work is underpaid or unpaid. We usually put our lives at risk to bear children and then, as Second Wavers anyway, we “composed” our lives to accommodate our families, in a way few men in this generation even considered. I’ll be very interested to see how the Millennials share all the work, both earning income and family work.

Paradoxically, the under-appreciated nature of women’s workforce participation has left us with a lot of hard-earned experience to share. Women have occupied the precariat — precarious work, on call, part-time jobs without benefits — for generations. The irony is, of course, that business schools are discovering that members of this cheap, disposable workforce actually know quite a lot about how to handle money. Recent statistics show that companies with more women on their boards earn higher profits than companies with fewer or no women on their boards.

Perhaps that comes from our work on non-profit boards. As a sign over one non-profit co-ordinator’s desk said, “We the unwilling, led by the unqualified, have been doing the unbelievable for so long with so little, that we now attempt the impossible with nothing…”

4. Similarly, any woman’s time is worth at least as much as any man’s of similar social rank, regardless how much they earn.

Specifically, family caregiving may be “free” on government books but the time involved is not “free” to the provider or the provider’s family. Many government cost-cutting measures (e.g., early hospital discharge, or shortening school years or days) just externalize caregiver costs, usually onto a presumed at-home partner, parent or dutiful child.

Women have been willing volunteers and true champions of progress historically — but part of the reason for that history is that we were excluded from positions of real power. The degree to which the education or health system depends on women’s unpaid caregiving or advocacy for their family members reflects the degree to which women’s perspective is still shut out of policy making.

5. A woman occupies a full person’s space in public, on the sidewalk, on theatre seat and in a doorway.

Not a child’s space, not a half space, not a scrunched-into-the-corner space, as often required, given that men tend to take up a space-and-a-half — a fact that has aroused plenty of comment lately. No sir, women have been saying, that extra inch or two on the edge of my airplane or bus seat is not fair game, and the onus is not on me to explain that having a stranger’s thigh cosy right up to my thigh invades my space. If a guy did that to you, you’d push back.

“The world doesn’t owe men extra space to get all comfy in,” writer Jenny Block pushed back in a recent blog post. “Public transportation is uncomfortable for most human bodies. And men taking up more space than their due, means that some people (read women) get to be extra uncomfortable.”

On the other hand, one factor that I think has changed a lot since the 1970s is women’s visibility. In those days, women’s media images included only very restricted roles, mainly mothers, secretaries, teachers or sexpots.

We were so excluded from the workforce that job titles often specified men, such as fireman, postman, policeman, businessman, alderman. Only men could be leaders, doctors, lawyers, judges, police officers, soldiers, Governor General or other authority figures — and that fact showed in every news article and broadcast. Men’s faces and men’s voices filled the media, usually with a male perspective.

When I started in journalism in the 1970s, the world was designed for, built by, and recorded by men. Women were largely invisible in print or broadcast news, current affairs or history, except for the entertainment and cooking segments, as contemporary studies proved by measuring column inches and minutes of broadcast time. And we’re still under represented in most of the media, but perhaps not as much as, say, people of colour are still under represented.

So in a perverse way, when almost all the public faces were male, men’s street harassment sort of made sense. As proprietors of public space, they were threatened when a woman became visible on a sidewalk or in a store.

Now, however, women have been visible in positions such as Governor General, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Prime Minister and Opposition leader. In broadcast news, the female-male anchor team has become standard and female commentators and foreign correspondents are no longer as rare as they once were.

What then accounts for the renewed rise in egregiously rude male behaviour? Economics usually accounts for a lot of bizarre behaviour, from people signing on to subprime mortgages to deadly Black Friday store stampedes over cheap video games.

Unemployed or underemployed men might be trying to get in touch with the feeling of being in control, by flailing at women. In the U.S., the Republicans are clearly trying to deflect economic rage by recommending tight controls on women’s bodies. Hey, it works for the Taliban!

Fortunately, technology offers women new tools for dealing with hasslers, such as Hollaback, a website that encourages women to record street harassment on their smart phones and upload the videos to the Hollaback website, for documentation, analysis, and mapping.

While progressives celebrate the momentum behind overdue recognition of LGBTQ rights, we might note that women’s rights have made remarkable progress too, considering that only 100 years ago (1914) we could not vote — or even own property in most provinces. In fact, until Married Women’s Property Acts rolled out across the Prairies in 1900, women essentially were property ourselves, like children or slaves or pets. Our fathers or husbands were our guardians, and held responsible for our behaviour.

This may be the origin of male privilege in public: in village life, any adult could chastise other adult’s chattels — “I’ll tell your husband” — to hold them to the village standard. Of course, feminism is the history of resistence to such self-anointed authority; but the idea seems particularly absurd to most young women in the 21st century.

Let’s remember that Canada made real progress towards gender equality over the 20th century, and especially since Charter equality rights came into effect in 1985. Brian Mulroney’s government was hostile to women’s equality and Stephen Harper’s government has been downright harsh on women’s issues (environmental issues, First Nations’ rights, research issues…) among others.

Remember what Gandhi said: “First they ignore you, then they ridicule you, then they fight you, then you win.” Well, they’re fighting us. That might be a more favourable sign that it appears.

More examples: Running While Female