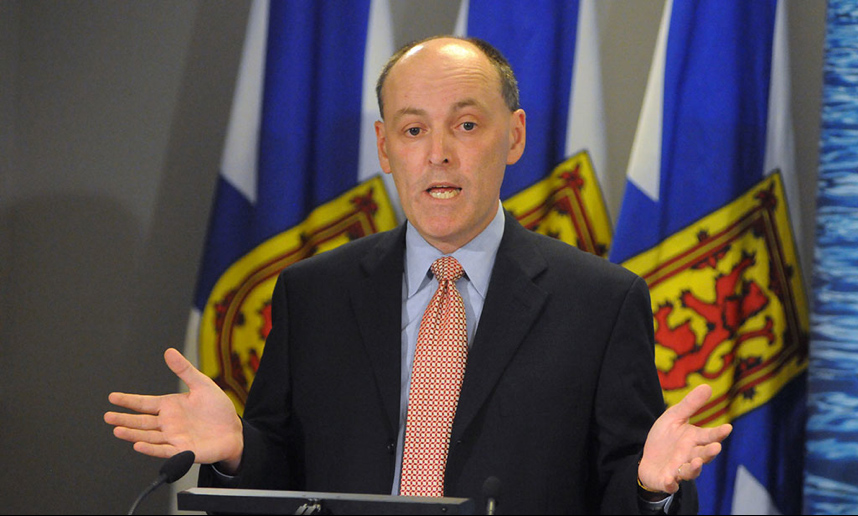

Graham Steele is a well-known figure on the Nova Scotia political landscape — even though he has ostensibly left the field. Steele was a former NDP MLA for the riding of Halifax Fairview (from 2001-2013); then Nova Scotia’s Finance Minister after the election of the Dexter government in 2009, before abruptly resigning from Cabinet on May 30, 2012 (for undisclosed reasons) to sit as a backbencher; before again returning to cabinet a year later on May 10, 2013 as Minister of Economic and Rural Development and Tourism (ERDT). Steele did not run in the October 8, 2013 provincial election that saw the defeat of the Dexter government, and has subsequently appeared as a political commentator, recently authoring the political memoir What I Learned About Politics: Inside the Rise — and Collapse — of Nova Scotia’s NDP Government (Nimbus, Halifax, $21.95).

Steele’s short (184 pages) memoir is an accessible and breezy read. From an insider’s perspective he correctly documents many of the problems with how politics is currently practiced, not only in Nova Scotia, but also in provinces across the country, and certainly at the federal level in Canada. There is a litany of well-known (and sometimes not so well-known) problems with the system. For example:

Steele’s short (184 pages) memoir is an accessible and breezy read. From an insider’s perspective he correctly documents many of the problems with how politics is currently practiced, not only in Nova Scotia, but also in provinces across the country, and certainly at the federal level in Canada. There is a litany of well-known (and sometimes not so well-known) problems with the system. For example:

• Money is scarce.

• Elected representatives sometimes have little knowledge and/or few skills.

• Constituency work (which some MLAs or MPs are adept at) has no relationship to the legislative knowledge or skills required in law making, let alone the knowledge of the matter and administrative skills required to effectively run a Ministry.

• For various political and media reasons, politics have become increasingly leader-focused. Thus, what happens when the emperor has no clothes, or is inept?

• Politicians are human, beset with the same failings of humans in other domains, and some can fight and blame, and lie, and deceive with alacrity as they scramble to try and attain their political ambitions.

• Politicians are obsessed with getting elected and/or re-elected.

• Civil servants can subvert or derail the efforts of elected representatives since they usually know their departments far better than the ministers, and the bureaucratic and administrative diversions and feints that can be employed. [Those with any doubts on this point should watch the BBC series, Yes Minister.]

• Election cycles are often shorter than real-life time cycles precluding approaches of issue development and resolution that are lengthier than four years.

• Much that transpires in legislatures and parliaments is an orchestrated charade where no one seriously debates, or even listens, choreographed for partisan purposes.

• Politics has become a hyper-partisan pursuit; consequently demolishing your political opponents and scoring points is frequently prized far beyond rational discourse, productive measures, co-operation, and other methods of sanely accomplishing anything.

• Money continues to be scarce.

Any astute political observer can add entries to this list, and Steele certainly does. And all of these points are correct. It comes across as a jaundiced and cynical view of politics. And, one could well grow jaundiced and cynical. The problem with Steele’s account is that there are more dimensions to politics than these.

One could easily come to Steele’s conclusions if one regards politics solely as a strategic, tactical, and logistical pursuit; a game in which one maneuvers around foes and obstacles; a kind of torturously complicated maze that continually frustrates one in getting from point A to B. However, two essential dimensions are missing in Steele’s account, and his view of politics.

1. Philosophy and policy

In Steele’s somewhat satirical/somewhat serious set of ten political “Rules of the Game” he writes, “Policy debates are for losers.” That’s because Steele sees politics as, on the one hand, a hyper-partisan free-for-all amongst political parties that are essentially no different from one another. “Attack, attack, attack. It’s just politics,” he writes. And, on the other hand a series of practical problems (e.g., negotiating shipbuilding contacts, keeping a ferry running; balancing a budget; sorting out MLA expense structures, etc.), that have no policy dimensions, and would have to be faced identically by any government of any political stripe. The only difference is how competently or not they are dealt with.

What’s missing in this is a clear political idea about what the enterprise of government should be doing and how it should be guiding the development of society. What values does one believe in? Democracy? Social justice? Equality? Meritocracy? Sustainability? Openness? Transparency? Accountability? Taxation? Engaged and proactive government? The environment? These are all core progressive values.

Or not? Examine neo-liberalism and you will find the antithesis of every one of these.

And, if you espouse progressive values, how precisely are they then developed and articulated?

This discussion isn’t simply an academic one for wonks and losers, but a critical component of what politics needs to be. Having clear philosophical and policy moorings helps anchor one to core values when it comes to all of the problems with politics that Steele articulates. It doesn’t make them disappear (although, there are productive ways to reform the system; see below) but it both guides day-by-day, issue-by-issue choices, and helps sustain energy and commitment, preventing politicians from being swallowed by the cynical vortex that swirls at their feet.

Political philosophy isn’t simply an exercise in abstract theorizing to be relegated to the dustbin whenever practical politics need to be employed, but rather a keen analytical knife with which to cut to the core of issues. For example:

Ships Start Here

Take the “Ships Start Here” shipbuilding contacts with Irving Shipbuilding, an area that Steele knows a great deal about, having signed the contract for the deal when he was Minister for ERDT. Was it really necessary to give the largest, industrial conglomerate in the Maritime provinces a $260 million forgivable loan (to grease the wheels of a $25-billion project from the federal government)? And this at the same time that cuts to education funding were being announced? As I wrote in my article, Election Nova Scotia: Orange Crush to Red Tide:

“There is a case to be made that government should be pro-active in spurring job-generation, and the Dexter government countered that the “loan” was tied to job creation and would, through tax revenues, be a net benefit to the province. However … it is not demonstrably clear that Irving Shipyards required this money to undertake the project, and if bridge financing was required, why not a repayable loan? Correct or not, this looks like corporate welfare on a grand scale.”

Without offering any evidence of why this is so, Steele simply asserts (p. 158), “But, the deal is a good one.” “Good” based on what set of policies and priorities? “Good” for whom?

Steele continues:

“The Irvings didn’t get rich by being pushovers… We haven’t heard the last of the shipbuilding deal. No matter what contract we sign, the Irvings will always push. That’s how they do business. They’ll come back again, and again, and again, over the life of the deal to push for better terms or a more favourable interpretation.”

I’ve no doubt that this is true. However, political values are the backbone one uses to resolutely push back; to not be a “push over.” To understand that the Irvings are not going to walk away from a $25-billion deal because they have to repay a loan that amounts to 1 per cent of the value of a contract. That a social democratic government prioritizes the needs of the 99 per cent, not those of the one per cent.

Affordable Living Tax Credit

In April 2010, Steele, as Finance Minister, ushered in a budget that included, amongst other things, an Affordable Living Tax Credit to “cushion” the impact of the two per cent HST increase that was also part of the budget, for households making less that $30,000. This was an admirable measure of which Steele writes (p. 137):

“Here’s another thing we [i.e., the NDP government] got no credit for: the affordable living tax credit returned $70 million to low-income households. It was explicitly designed to more (Steele’s emphasis) than compensate those households for the HST increase, by about $20 million. They would end up with more money than they had before.”

Commendable. So, why didn’t the government get credit for this poverty reduction measure? Steele continues:

“But we didn’t make a big splash out of it, and so our own people — the anti-poverty activists and even some of our own MLAs — missed what we were doing.”

Say what? Government caucus members themselves were unaware of what the government was doing? And by intentional design? And if not MLAs, then how would anti-poverty activists, let alone those living in poverty, find out about this? Why ever not make a “splash” — large or small — so that informative ripples would radiate to those concerned?

Why? As I reported in Orange Crush to Red Tide, in a session whimsically titled The future of the Status Quo: The left after the NS election held at University of King’s College, former MLA Howard Epstein (who did not re-offer in the 2013 election), informed the audience that:

“The party leadership determined the government would not publicize this because of the apprehension that assistance to lower income people doesn’t sell well with the middle classes.”

Say what? Political values should provide ideological moorings, guiding not only what is done, but also why and how this is communicated, so that the reasons for government actions are clearly conveyed to stakeholders and the electorate. How else can they evaluate the quality and competency of their government?

Where are we bound?

Steele develops an appealing metaphor for government as an actual ship of state (page 120). The officers (i.e., government) may change, but the ship is already a-sail. The officers haven’t been trained in nautical operations or navigation — and there are no maps. Renovations have to be done with the passengers on board. The seas can be rough. “And every four years the passengers get to decide if they want you to stay on the bridge or give someone else a try.” Too true.

Steele develops an appealing metaphor for government as an actual ship of state (page 120). The officers (i.e., government) may change, but the ship is already a-sail. The officers haven’t been trained in nautical operations or navigation — and there are no maps. Renovations have to be done with the passengers on board. The seas can be rough. “And every four years the passengers get to decide if they want you to stay on the bridge or give someone else a try.” Too true.

However, the real issues are not the strategic, tactical or logistical ones alluded to here — and there’s no question that they are important — but rather, where is the vessel going, and what is the best route to get there? Having taken control of the ship of state ostensibly, “to make a difference,” where does the government intend it should sail?

Without ideological moorings, it can easily become a ship of fools. The wind blows left; the vessel drifts left. The wind blows right; the vessel drifts right. There are no maps? How about getting out the compass and sextant — or these days the radar, sonar, and GPS — to create some? And let the passengers and crew in on the discussion. As Steele points out they have, “plenty of ideas… about where the ship should be going and how it should get there.” Some of them may be good ones.

2. How to conduct a better politics

Thus, given that the problems and obstacles that Steele enumerates are true — and the dead hand of the status quo constantly tries to take the tiller; and there are “escape hatches” politicians have at their disposal to avoid doing anything substantive; and there are no lifeboats, so we’re all stuck on board, sink or swim — how can we conduct a better politics (πολιτικός meaning “of, for, or pertaining to citizens.”)

Steele has an idea. In an op-ed entitled Let’s walk a decade in unity-platform shoes, Steele proposes a decade long “unity” government based on the “platform” of the Ivany Report (see below) a, “peacetime equivalent of a wartime coalition government,” as both Steele and Ivany phrase it. Steele is certainly correct in his observation that, “politics-as-usual is not working.” And in that regard, ideas to do something better are always welcome. That said, the ideas Steele proposes would, in large measure, do precisely the wrong things. Why?

A. Electoral reform

One of the most important and dramatic ways we could change Canadian politics is by changing the electoral system, from the flawed and archaic, first-past-the-post (FPTP) system we currently have, to a system of proportional representation (PR) that creates not only a fairer and more democratic electoral system, but also creates the context for political parties cooperating in far more effective ways. Why is this?

One of the most important and dramatic ways we could change Canadian politics is by changing the electoral system, from the flawed and archaic, first-past-the-post (FPTP) system we currently have, to a system of proportional representation (PR) that creates not only a fairer and more democratic electoral system, but also creates the context for political parties cooperating in far more effective ways. Why is this?

Here’s an example: in states that have governments elected through proportional representation systems, politicians often dislike it. Why? They almost never get a majority government and have to form coalitions with their political opponents. They have to sit around the cabinet table coming to decisions by consensus and compromise. They have to cooperate. It’s really hard.

Citizens, in contrast, frequently like proportional representation. Why? Their representatives have to form coalitions with their political opponents, coming to decisions by consensus and compromise. They have to cooperate. It’s hard work. But, it leads to greater inclusivity; more viewpoints are represented at the table where decisions are made. Consequently, there is greater “buy-in” on the part of the electorate. It produces better governance.

When I recently put this question to Steele at a session organized by the Dalhousie University Political Science Department, he replied that he, “doesn’t want to devote even one minute to thinking about electoral reform and proportional representation,” illustrating how little he understands electoral reform and its transformational political impact. Electoral reform would much more effectively and democratically accomplish what he suggests through his “unity government” proposal.

There is a reason why 81 democracies throughout the world have adopted systems of proportional representation — it works far better than FPTP.

In his response to my question Steele criticized the party-list systems of PR as not producing elected representatives responsible to a particular constituency. True enough, however, that’s not the system of PR that the New Democratic Party in Canada supports, or what the Law Commission of Canada proposed in its comprehensive study of electoral reform in the country. Both recommend MMP systems

Mixed Member (MMP) systems of PR have elected representatives from each constituency elected in the much the same way as is done at present, but electors also have a second vote (for party) that is then used to top up the list of parliamentarians to the proportional level of support that the party receives in the election. It’s a simple system that most people can understand in 30 seconds, which sacrifices nothing in terms of ridings having an elected representative to whom voters can turn for constituency issues. Steele’s critique of party-list systems is a red herring; constituency responsibility doesn’t have to be sacrificed to reform the electoral system.

B. The Ivany Report

The “Ivany Report” (chaired by Ray Ivany, president of Acadia University; hence the appellation), a.k.a. The Report of the Nova Scotia Commission on Building Our New Economy, a.k.a. Now or Never: An Urgent Call to Action for Nova Scotians, makes a compelling case that Nova Scotia needs to do things differently — something both essential and good. However, what it proposes is in many respects a doubling-down on the neoliberal policies that got Nova Scotia (and much of the rest of the world) in the economic and environmental mess we find ourselves in.

The “Ivany Report” (chaired by Ray Ivany, president of Acadia University; hence the appellation), a.k.a. The Report of the Nova Scotia Commission on Building Our New Economy, a.k.a. Now or Never: An Urgent Call to Action for Nova Scotians, makes a compelling case that Nova Scotia needs to do things differently — something both essential and good. However, what it proposes is in many respects a doubling-down on the neoliberal policies that got Nova Scotia (and much of the rest of the world) in the economic and environmental mess we find ourselves in.

The report consistently fakes left and runs right. Its focus is on developing international commerce, lowering trade barriers (translation more “free trade”), generating greater labour “efficiencies” (translation: lower wages and benefits), boosting big business, “restructuring” (translation: cutting) public services on the basis of “value for money,” and giving corporations tax holidays in return for investment. It consistently emphasizes private sector entrepreneurism as the solution to Nova Scotia’s economic and demographic crisis, and de-emphasizes the role of the public sector. It’s a free-market based approach, which for a small jurisdiction like Nova Scotia means seceding control to multinational, corporate interests.

The Ivany Report’s “Team Nova Scotia” cheerleading would have the province dynamically plug into the global corporate economy giving local “intrapreneurs” (i.e., those that act like entrepreneurs while encased within larger economic structures) opportunities to develop niches within a market dominated by multinationals. It simply fires the democratic and egalitarian imagination … not.

Lacking is an articulated vision that examines how Nova Scotia might be able to develop itself, locally and sustainably, for the benefit of Nova Scotians, rather than succumbing to the baubles and beads that multinational corporations offer in return for our resources, environmental sustainability — and our souls. An alterative path of developing our society and economy based on local and regional concerns and imperatives, along sustainable pathways, with a reinvigorated public sector, galvanizing cooperative structures (i.e., commercial structures that value social goals and local objectives and not simply corporate profits, shareholder dividends, and executive bonuses) as a counterbalance to corporate entrepreneurialism.

As Naomi Klein’s book This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate forcefully points out, this philosophy of unregulated, global, market economics has caused not only massive inequality and repeated economic disasters, it is also incompatible with the environmental basis of life on earth. In common with Steele and Ivany, Klein also calls for a Marshall Plan — but of a very different sort. In the words of Angélica Navarro Llanos, Bolivian ambassador to the World Trade Organization (WTO):

As Naomi Klein’s book This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate forcefully points out, this philosophy of unregulated, global, market economics has caused not only massive inequality and repeated economic disasters, it is also incompatible with the environmental basis of life on earth. In common with Steele and Ivany, Klein also calls for a Marshall Plan — but of a very different sort. In the words of Angélica Navarro Llanos, Bolivian ambassador to the World Trade Organization (WTO):

“If we are to curb emissions in the next decade, we need a massive mobilization larger than any in history. We need a Marshall Plan for the Earth. … It must get technology onto the ground in every country to ensure we reduce emissions while raising people’s quality of life. We have only a decade.” – in This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate.

A Marshall Plan rather like the one rolled out in 2008 by western nations who deployed trillions of dollars to bail out the banking sector, brought to its knees by its own deregulated, free market excesses. A massive re-deployment of technology and resources to simultaneously move the planet towards a sustainable, low-carbon economy, and to battle the systemic poverty and inequality that has been foisted upon the world through contemporary, corporate, capitalist structures. A redistribution of resources and wealth to save the planet from heat death.

A peacetime equivalent of a wartime coalition government is required, but one that would take us away from the unregulated, multinational, corporate, economic model that has:

• Demonized taxation as a way citizens invest in their own society to have it reflect their needs and desires;

• Privatized public assets. Look what happened in Nova Scotia to our formerly public power corporation, now in Emera’s private hands — rates have gone up, service has declined and $100 million in corporate profits annually flows out of the province (see Power to the People for further information);

• Cut public services. Look everywhere around you at the state of the roads, education, health care, universities, etc.;

• Is in the process of destabilizing the climate of our planet. As United States President Barak Obama said at the UN Climate Summit in September 2014: “We cannot condemn our children, and their children, to a future that is beyond their capacity to repair.”

Politics as usual isn’t working. Change is critical. But not simply any change. We require change that takes us out of the morass we are in, rather than entrenching us ever more deeply in it. For this, political principles and vision are required. At sea, one must keep one’s eyes on the horizon and know where one is sailing to have a chance to reach a desired destination. Otherwise, I’m reminded of the words of Polish satirist Stanislav Lec who wrote, “It’s true we’re on the wrong track, but we’re compensating for this short-coming by accelerating.”

Christopher Majka is an ecologist, environmentalist, policy analyst, and writer. He is the director of Natural History Resources and Democracy: Vox Populi.