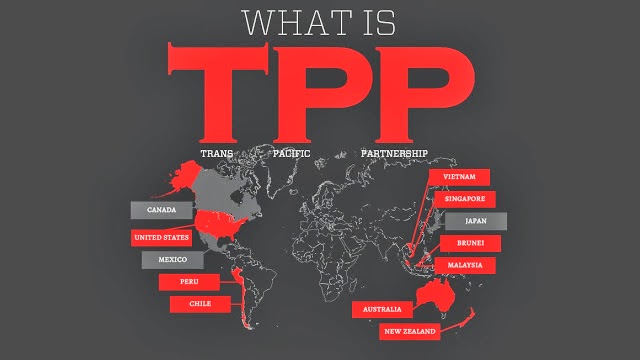

If you believe the October 27 joint statement released in Sydney, Australia at the conclusion of three days of meetings between the trade ministers of the 12 nations involved in talks aimed at creating the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), things are looking good for the deal.

“We are pleased to report that, over the past weeks, we have made significant progress on both component parts of the TPP Agreement: the market access negotiations and negotiations on the trade and investment rules, which will define, shape and integrate the TPP region once the agreement comes into force,” reads the statement. “We consider that the shape of an ambitious, comprehensive, high standard and balanced deal is crystallizing.”

The statement goes on to say that the ministers have passed “the baton back to Chief Negotiators to carry out instructions we have given.” The Chief Negotiators, who met for a week in Canberra prior to the ministers meeting are continuing negotiations in Sydney, and trade ministers have pledged to meet again “in the coming weeks,” likely on the sidelines of the meeting of the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) meeting in China in early November.

Sounds promising (or ominous), doesn’t it?

But given the extreme secrecy surrounding the TPP negotiations, it’s hard for anyone to truly know what to make of the declaration’s rosy spin on the progress that was made. Similarly glowing declarations were made in Singapore in February 2014 (“we made further strides toward a final agreement”), and in December 2013 (“we have made substantial progress toward completing the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement”) and Bali, Indonesia in October 2013 (“Negotiators have made significant strides toward realizing each of the five defining features of this historic agreement.”)

Of course, the Bali statement started with the words to TPP leaders, “Based on your instruction to seek to conclude the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement this year,” which, with the benefit of hindsight, clearly didn’t work out as planned.

“The ministers have repeated much of the same hype as previously about making ‘significant progress’ and ‘setting the stage to bring the negotiations to finalisation,'” according to Aukland, New Zealand Professor Jane Kelsey who was in Sydney for the ministerial. As Kelsey says, “Nothing is clear, that’s the problem. It’s still a muddle.”

So what’s the best guess at where things are really at?

While some legitimate progress was apparently made on the stumbling block of market access, the major disagreement between the TPP’s major powers, Japan and the United States, which has been preventing progress towards a final deal seems yet to be overcome. According to Akira Amari, Japan’s economics minister, “There is no prospect for an agreement on market access [between Japan and the United States] at the moment.”

Mike Froman, the U.S. trade representative, who chaired the Sydney meetings despite the fact that the host nation typically chairs, also seemed hesitant to say that a deal was imminent, saying, “The key thing is to come up with and achieve the ambitious, comprehensive, high standard agreement and we will take whatever time is necessary to do that.”

Thanks to a May 2014 version of the test released just two weeks ago by Wikileaks, we also know that major differences between the countries likely remain in the intellectual property chapter. And to be clear, that’s a good thing given the far-reaching impacts the TPP would have if the U.S. can push through its position successfully (over the objections of many countries, including Canada) on everything from access to medicines to an open Internet.

Another major consideration is the internal politics south of the border, where demands from Congress for greater market access and action on so-called currency manipulation have stopped the approval of “fast track authority” for U.S. President Obama, which is widely seen a a necessity if the TPP has any hope of becoming a reality.

“With no chance that President Obama will get Fast Track trade authority from the 113th Congress and decent prospects that he never will, it’s becoming increasingly clear that either congressional demands relating to inclusion of currency disciplines in TPP will have to be met for a deal to get through Congress,” according to Lori Wallach, the director of US-based Public Citizen’s Global Trade Watch. “Yet to date U.S. negotiators have not even raised this issue.”

So the TPP could very well be dead in the water, as many are suggesting.

But despite all the outstanding issues, negotiators are yet again running out of time on a self-imposed deadline, this time the public pronouncement from earlier this year by U.S. President Obama who said, “My hope is that by the time we see each other again in November, when I travel to Asia, we have got something.”

By the time APEC leaders meet in Beijing on November 10 and 11, and the G20 leaders meet in Australia, the U.S. midterm elections, and the political risks of an unpopular trade deal, will be in the rearview mirror. And the longer talks on the TPP stretch on, the more pressure there is to show some progress and to ultimately seal the deal. The question remains what countries like Canada will be willing to sacrifice to finalize the TPP.

But a more critical question for citizens in the dozen countries involved in TPP negotiations is when we’ll actually get to see what’s in the deal, so we can stop speculating about what’s happening behind closed doors, and start talking about whether its something we even want.