I am loathe to enter into this conversation further than I have already in various spaces online as it has become so heated and divisive, but am too frustrated to shut up (despite the fact that I’m aware many will respond by telling me to do just that — shut up — and isn’t that what women should always be doing, after all? Shutting up? Surely women have said enough…).

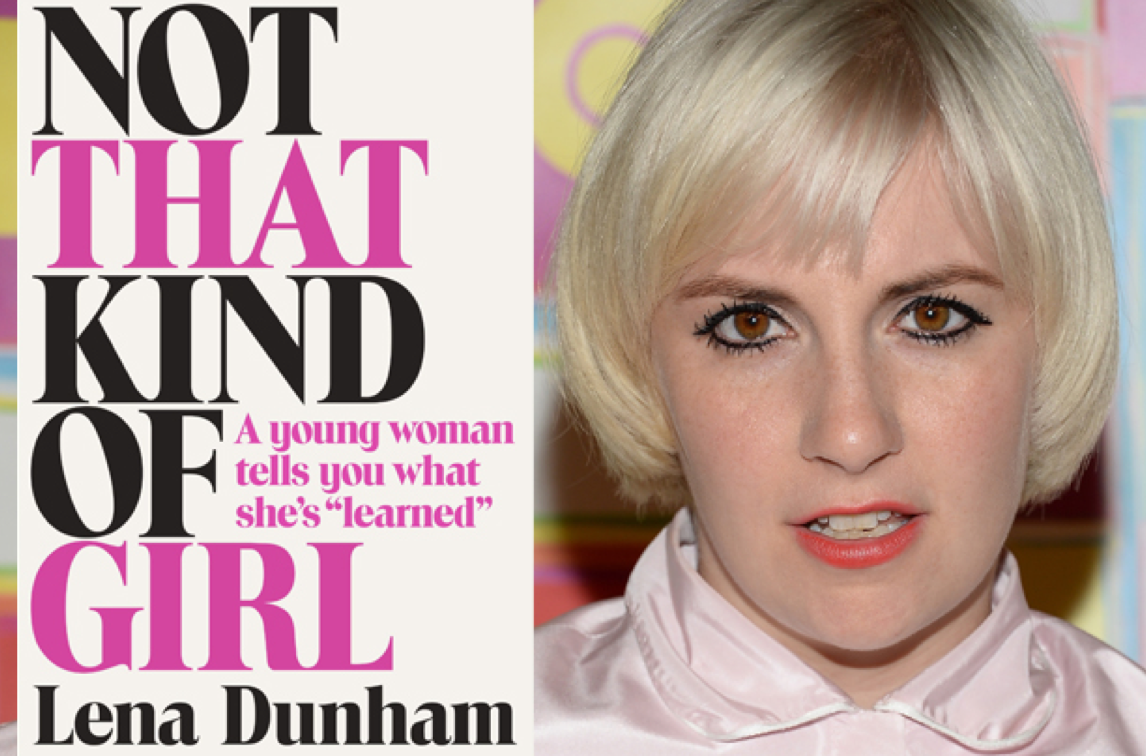

In case you somehow managed to miss it, conservative and anti-feminist, Kevin D. Williamson, wrote a diatribe against Lena Dunham, disguised as a “book review,” accusing her of sexually abusing her younger sister, Grace. Another extreme-right site, TruthRevolt, followed suit, publishing a blog post with the headline: “Lena Dunham Describes Sexually Abusing Her Little Sister.” The accusation is based particularly on this passage, from Dunham’s book, Not That Kind of Girl:

“Do we all have uteruses?” I asked my mother when I was seven.

“Yes,” she told me. “We’re born with them, and with all our eggs, but they start out very small. And they aren’t ready to make babies until we’re older.” I look at my sister, now a slim, tough one-year-old, and at her tiny belly. I imagined her eggs inside her, like the sack of spider eggs in Charlotte’s Web, and her uterus, the size of a thimble.

“Does her vagina look like mine?”

“I guess so,” my mother said. “Just smaller.”

One day, as I sat in our driveway in Long Island playing with blocks and buckets, my curiosity got the best of me. Grace was sitting up, babbling and smiling, and I leaned down between her legs and carefully spread open her vagina. She didn’t resist and when I saw what was inside I shrieked.

My mother came running. “Mama, Mama! Grace has something in there!”

My mother didn’t bother asking why I had opened Grace’s vagina. This was within the spectrum of things I did. She just got on her knees and looked for herself. It quickly became apparent that Grace had stuffed six or seven pebbles in there. My mother removed them patiently while Grace cackled, thrilled that her prank had been a success.

Now, I don’t have any children. I do not know for certain what is “normal” behaviour for seven year old girls. I am not a child psychologist. But the mothers I’ve spoken to tell me this is pretty run-of-the-mill weird-kid behaviour. From where I’m standing, despite the fact that I never personally looked inside anyone’s vagina when I was a kid, this strikes me as pretty average. Kids are weirdos. They do weird, awkward, inappropriate things. As evidenced by a collection of stories from anonymous women, detailing their own weird, inappropriate, awkward kid behaviour compiled on a Tumblr account called Those Kinds of Girls.

In a piece for Jezebel, Jia Tolentino asked Debby Herbenick, PhD, an associate professor at Indiana University, writer for the Kinsey Institute, and author of Sex Made Easy what she thought about the incident. I though her response was useful:

Anyone who has worked in K or pre-K will tell you that you’re often having to remind little children not to touch their genitals and to keep their hands to themselves, because genital exploration is very, very common among young children. Ask any parent of young children and they will also have stories to tell (I’ve worked with parents of young children for years about how to talk with their own children about bodies, puberty, and so on and these instances always come up: not just about kids exploring their own bodies but about how kids explore with each other).

Dunham’s story is not one of sexual exploration and she doesn’t describe any sexual acts. The story she tells is one of bodily exploration; sex is not a part of it. Her story also includes her sister’s own exploration in that it turns out her sister had been putting pebbles inside her own vagina (some small girls put things in their vaginas—toys, pebbles, Legos, etc—there is a case study of a 4 year old girl who put a Bratz doll in her vagina).

People who are attaching sex to these stories seem to equate the genitals with sex, but that’s not how young children see their genitals. Dunham’s story is not an uncommon one. The research (and any preschool or home with young children) is full of stories of childhood ‘play’ not so different than this one.

Experts on child sexual abuse, parenting, sexual health, and psychology also say that the stories Dunham describes fit well within the realm of “normal” childhood behaviour.

I hear that many people perceive this behaviour as inappropriate and/or disturbing, and that some found it triggering to read. Those are perfectly reasonable responses. It isn’t ok for people — even if they are kids — to touch other people’s genitals without consent. Kids need guidance with regard to healthy boundaries and touching and bodies. That’s why, when things like this happen, it is the responsibility of parents to have a conversation with their kids about boundaries and consent and touching and other people’s bodies. I hope that when Dunham went to tell her mother of her discovery, she had a conversation like that with her.

So these are all relevant and worthwhile things to discuss, as feminists and people who care about kids and people and women. What isn’t relevant is whether or not you like Lena Dunham or Girls. There are plenty of valid criticisms of Dunham’s privilege, of her work, and of what she represents. And none of those things make her a child molester. I like her work. You don’t. That’s ok. My liking Girls and Tiny Furniture has nothing to do with my, or any other of the feminist responses that say Dunham’s behaviour doesn’t make her a child abuser. But what’s clear is that many of those leading the Tweet-war on Dunham hate her and hated her long before they didn’t read her book, but came across some intentionally misconstrued excerpts generously provided by some folks who have a vested interest in taking away women’s reproductive rights (and who hate Dunham specifically because she advocates for abortion rights), proving that women routinely falsely accuse men of rape, who painted Dylan and Mia Farrow as malicious liars with respect to their allegations against Woody Allen (and believe, more generally, that “feminists are dreadful and lie all the time”) and, I’m sure, would very much like to show us that “Women are abusers, too! Sexual abuse isn’t gendered — SEE!” despite that fact that almost 100 per cent of perpetrators of sexual violence in childhood are men. Ask these folks how much they give a shit about Allen or Kelly or Ghomeshi’s victims? And why suddenly they care oh-so-much about supposed child abuse?

If you don’t think this was all initiated with the specific intention of attacking women’s reproductive rights, the feminist movement, and women in general, you’re not paying attention and I certainly won’t be joining in in your faux-, anti-woman, self-indulgent, cookie-seeking, transparently-desperate-for-Twitter-followers, hate-activism.

The Twitter rage machine has little interest in nuance or in honest conversation — it feeds on the extreme. No one is holding social justice Twitter accountable. Which is why you’ll see gratuitous comparisons between Dunham and actual sexual predators and abusers like Woody Allen, R Kelly, and Jian Ghomeshi in abundance.

To compare a seven-year-old girl who was curious to know whether or not her younger sister had “eggs” inside of her and decided to check it out, to an adult male who intentionally molested, exploited, beat, raped, traumatized, and abused girls and/or women is a completely ridiculous, destructive, and irrational thing to do. Demanding that Planned Parenthood — an organization that is absolutely pivotal for American women — #DropDunham under threat of pulled support and donations is similarly unhelpful. To, you know, women. That is who we are purporting to care about, yes? Women? Remember them? (Luckily a number of feminists responded by donating extra to the organization in order to show support and counter the ridiculously destructive hashtag.)

None of this “Lena Dunham abused her sister” narrative seems to be rooted in concern for her sister, who is decidedly fine. And for those who are concerned about whether or Dunham has consent from her sister to publish these stories, here is her statement published on TIME today:

I am dismayed over the recent interpretation of events described in my book Not That Kind of Girl.

First and foremost, I want to be very clear that I do not condone any kind of abuse under any circumstances.

Childhood sexual abuse is a life-shattering event for so many, and I have been vocal about the rights of survivors. If the situations described in my book have been painful or triggering for people to read, I am sorry, as that was never my intention. I am also aware that the comic use of the term “sexual predator” was insensitive, and I’m sorry for that as well.

As for my sibling, Grace, she is my best friend, and anything I have written about her has been published with her approval.

It seems, rather, to be focused on taking Dunham down. And as far as I’m concerned, we (should) have bigger fish to fry.

Dunham’s stories aside, I worry about how this kind of behaviour and response impacts women’s ability and willingness to write the truth. I want women to be able to tell the truth — no matter how weird, messy, or inappropriate that truth is. I want them to be able to tell the truth even if it makes some people uncomfortable. Certainly I want them to be able to tell the truth about being a weird, inappropriate, curious seven year old girl without being accused of sexual abuse (which, by the way is a very serious crime).

Lena Dunham isn’t the epitome of feminism. She’s also not a child molester. Step away from your keyboards, look around, find the real enemy. He’s thrilled right about now.