Western Canadian Select, the price at which tar sands crude is sold, could average at about half of what it was last year. This could have a major impact on the electoral prospects of the Harper Conservatives in the federal election expected on October 19.

That’s because the TD Bank is now projecting federal budget deficits for this coming year and the following year. TD senior economist Randall Bartlett says, “The conclusion is unambiguous. In the absence of new measures to raise revenues or cut spending, TD is projecting budget deficits in fiscal 2015-16 and 2016-17.”

TD forecasts an average price of oil at $67 a barrel in 2015. That would mean a $2.3 billion federal deficit in 2015-16 and a $600 million deficit in 2016-17. But Goldman Sachs says the price of oil will average at $47.16 per barrel. That would mean a $4.7 billion deficit in 2015-16 and a $2.4 billion deficit in 2016-17.

This is significant because as recently as October 2014 a $6.4-billion budget surplus was expected in 2015-16 meaning, as the National Post reported, “The Harper government [was] gearing up for a bonanza tax-cut giveaway in its fall fiscal update that would see cheques landing on voters’ doorsteps [in the] spring [just months before the election].”

The falling price of oil is also changing the balance of power in the country.

Alberta is now expected to face budget deficits until 2018. The province had projected a $1.5-billion surplus, but is now looking at a $500-million deficit. And premier Jim Prentice says the forecast average price of $75 a barrel would mean a $4.9 billion deficit in 2016-17. If the price persists at below $50 a barrel, it would be a deficit of about $10 billion. On the other hand, the economies in voter-rich Ontario, Quebec and British Columbia (that will have 241 seats in the new 330-seat House of Commons), are expected to benefit from the lower price of oil and a lower dollar given that helps with manufacturing, exports and U.S. tourism.

And Harper, who has prided himself as a sound fiscal manager, is facing an economy with higher interest rates.

Don Pittis, the senior producer of CBC’s business unit, says, “Oil is just part of the problem. The Canadian economy continues to lose jobs while the U.S. economy surges. And that adds an extra difficulty. As the economy heats up south of the border, the U.S. central bank could begin to raise rates, pushing Canadian long-term interest rates higher. Higher rates are not good for Canadians.” Bank of Canada governor Stephen Poloz says that hits the cash flow of ordinary people.

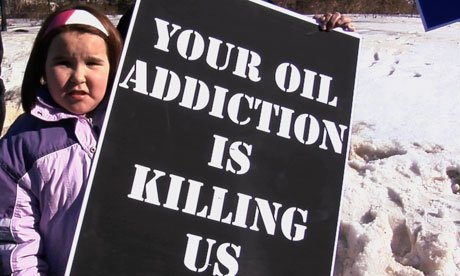

Pittis adds, “It’s difficult [for the Harper Conservatives] to hand out subsidies to the energy sector after telling everyone else in Canada to let the market decide. [Simon Fraser University economics professor Richard] Harris doesn’t rule that out, but any subsidies would have to be huge to have any more than a token impact. It would also leave the Conservatives open to opposition criticism of favouritism and recklessness. …[York University election specialist Robert] MacDermid says the Harper Conservatives will [already] take political heat for identifying so wholeheartedly with the energy industry.”

Toronto Star columnist Carol Goar writes, “If Prime Minister Stephen Harper had shown an ounce of contrition over his ill-fated plan to make Canada a global energy superpower, voters might be inclined to give him a break. He couldn’t have known the price of oil would drop by 57 per cent since last June. …[So] what prevents fair-minded Canadians from seeing him as a victim of circumstances? The first impediment is his absolute refusal to admit he misjudged Canada’s prospects. Even now, with the bottom dropping out of his budgetary calculations, Harper insists he is a masterful economic manager, the only safe choice for prudent voters. His skewed self-image and his unwillingness to adjust to events stifle any fellow feeling.”

Goar concludes, “It is unfortunate the nation can’t separate the prime minister’s policy miscalculations from the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune. But he chose his style of leadership. He picked his tactics. He assumed the goodwill of the people was expendable.”

Harper took the office of prime minister on February 6, 2006 — almost a decade ago now. Most polls at this point show that at best he can expect to lead a short-lived Conservative minority government. That could all change at some point over the next nine months with a dramatic event in his favour, but the polls for the past three years have consistently not given any party the prospect of a majority government. And as Toronto Star national affairs writer Tim Harper comments, “For this prime minister, anything short of another majority is a defeat.”

It seems within reach that voters will say it’s time for a change this October.