The Harper government gives five reasons why Canadians ought to be happy with its proposal to double the maximum contribution to the Tax-Free Savings Account. Examine each of its points more closely, however, and it’s clear that the TFSA carries far higher risks than rewards — for individual Canadians as well as for the economy as a whole.

Let’s unpack the government’s arguments one by one:

1. The TFSA helps people save

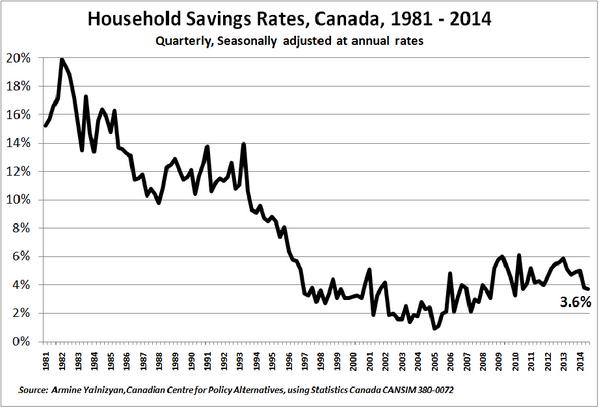

The evidence certainly doesn’t support this statement. TFSAs first saw the light of day in January 2009 at a time when the savings rate had already been climbing for four years. It has been highly variable since 2009, and has dropped since 2013 — the same year, by the way, that the maximum contribution was raised from $5,000 to $5,500.

Economists have consistently found that the main determinant of household saving is not tax rates but interest rates. The higher interest rates go, the more motivated people are to take advantage of them. But there’s no escaping the cold reality that people can’t add to their savings if they don’t have enough income to save. The fact is that hourly wages (adjusted for inflation) for most Canadians have been going nowhere in recent years.

These trends suggest that the TFSA does not measurably impact savings rates; but it measurably rewards the privileged few who are able to save.

2. The TFSA is wildly popular

Despite the heraldry of government and banks’ marketing campaigns, only 36 per cent of eligible Canadians have opened a TFSA. An even smaller proportion of Canadian households participate in the program.

Roughly 26.7 million Canadian residents were eligible to contribute to a TSFA in 2012. Yet only about 9.6 million had opened a TFSA account, some more than one, giving rise to the 11-million figure being used in government statements. Those are accounts, not people.

While the number of TFSA account holders has risen over time, the pace of growth is slowing. However the number of Canadians who have been able to “max out” their contribution room has been falling every year since the first, in absolute and relative terms. (The maximum allowable amount is currently $5,500 a year, and a cumulative $36,000 since the inception of the program.) Only 2.3 million — 8 per cent of eligible Canadians — have maximized their TFSA contributions during the first four years of the program.

Without doubt, more people have opened a TFSA since 2012. The Canada Revenue Agency will release data on 2013 contributions later this year. But even with the addition of another year — or two, or three — nowhere near the majority of Canadians has derived any benefit from this tax shelter.

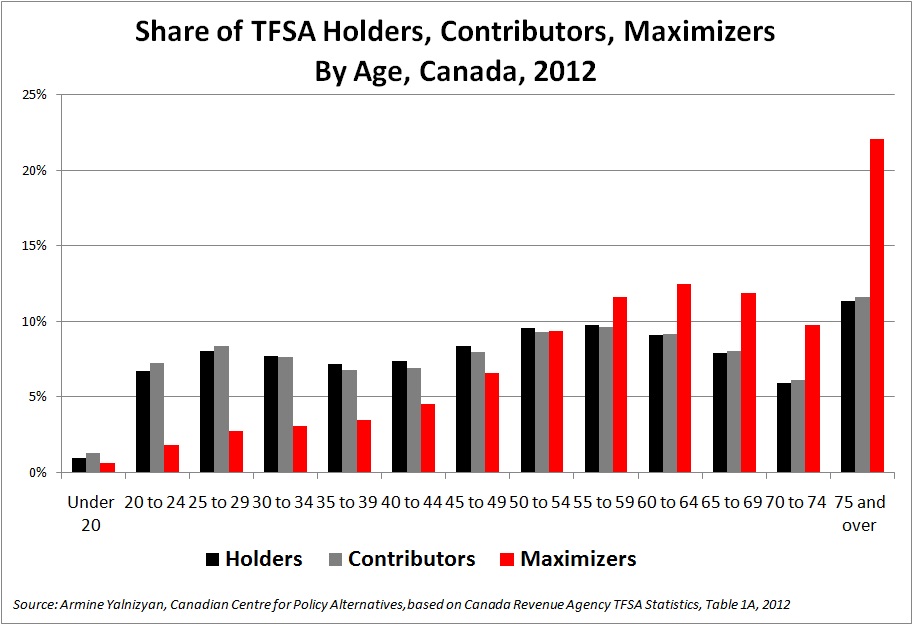

3. The TFSA benefits young Canadians

Again, data show young Canadians aren’t the primary beneficiaries of this program. The rate of increase in participation since the program’s inception has risen most rapidly among the under-35 age group. But we should not confuse a rate of increase with actual numbers. TFSAs are much more popular among older Canadians. The reason is simple: older people derive the biggest benefit from the program, using it as a way to top up retirement savings after bumping up against their RRSP limits.

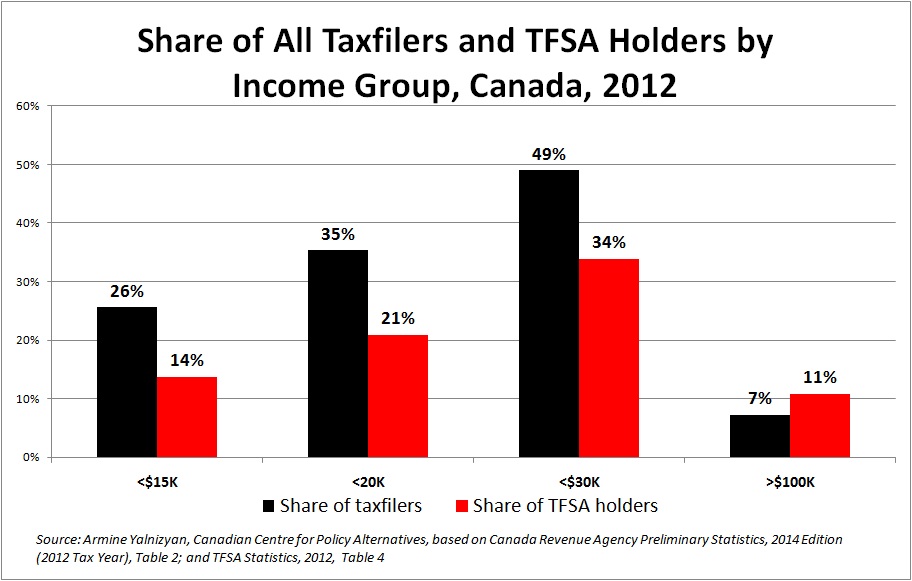

4. The TFSA helps low-income Canadians

At least part of the program’s original intent was to encourage saving among Canadians who could not reasonably expect to benefit from an RRSP. Furthermore, tax forms don’t include income from a TFSA, so it isn’t included in eligibility tests for public income security programs. That increases the numbers eligible, and reduces claw-backs that apply as taxable income rises.

As things turned out, those who benefit most from a TFSA are more likely to be rich than poor, and low-income Canadians are less likely to hold a TFSA than higher-income Canadians.

A U.S. tax-shelter scheme, known as the Roth IRA (Individual Retirement Arrangement), is similar to the TFSA, but explicitly excludes participation by tax filers with high incomes (above US$129,000 for singles, US$191,000 for joint filers). President George W. Bush tried three times (2003, 2004, and 2005) to introduce a program without these income restrictions, in other words, like the Canadian model. But Congress rejected the plan each time on the grounds that it would disproportionately benefit the wealthy.

Recent studies by the Parliamentary Budget Officer and Professor Rhys Kesselman — an award-winning economist and tax expert at Simon Fraser University who, with Finn Poschmann, helped introduce the TFSA idea to Canada — point to another serious shortcoming. They estimate that, without any change to the rules, the TFSA will add an extra $4 billion in costs to the Guaranteed Income Supplement, the income security program of last recourse for impoverished seniors. This is because the program does not count incomes that flow from TFSAs in their eligibility test.

That $4 billion eats a big chunk of the $10.8 billion in expenditure reductions that will be realized by rolling back Canadians’ eligibility for Old Age Security by two years, from age 65 to 67.

OAS changes are not pure “savings.” They shift financial costs to Canadian households and to provincial budgets.

About 35 per cent of Canadians have retired early because of ill health, disability or the need to care for family members. Pushing back income support to age 67 means many will have to work longer, which will saddle households with extra costs to care for young children, the elderly and the unwell. Some of these 65- and 66-year-olds who cannot work more will be left with no choice but to exhaust their savings and possibly turn to welfare. That, in turn, will put a bigger fiscal burden on the provinces.

The combined effect of the OAS and TFSA measures gives one group of wealthy elderly Canadians more cash in their pockets while taking cash out of the pockets of some of our most vulnerable seniors.

5. The TFSA puts money back in our pockets

While a bigger tax-free savings account will put more cash in some Canadians’ pockets, that money can’t buy functioning infrastructure and livable communities.

Think of the TFSA like a Contact-C™ policy measure, creating a time-release fiscal headache as it develops. Choices between cutting services or raising taxes will become increasingly stark because the amounts at play are very large.

Kesselman estimates if the TFSA program had been fully mature today (meaning it had been around for a generation of savers), it would have taken a $15.5-billion bite out of federal revenues this year — which are roughly $145 billion — and another $9 billion out of provincial coffers.

The government’s promise to double contribution limits would cost another $14.7 billion for the feds and $7.6 for the provinces by 2060. Whether you see that as a promise or a threat, it’s a hefty price to pay for a scheme that would benefit only 8 per cent of Canadians today, a group that will shrink over time.

The higher TFSA contribution limit will cost us seven times as much as the government’s much-criticized income-splitting program, while benefiting fewer than half the number of people. (Only 15 per cent of Canadian households, the vast majority most of them wealthy, will see any benefit from income-splitting. That program now bears a price tag of $1.9 billion, nestled in a “family tax cut” package that will cost $5.5 billion this year.)

As Kesselman put it: “If one were to rank between two nasties, the proposal to double TFSA limits is by far the nastier.”

There is a more sensible way

Billed as a populist measure that’s good for everyone, the proposed increase in TFSA contribution limits will primarily benefit Canadians with incomes over $200,000. They’re the only ones constrained by current RRSP plus TFSA contributions limits. There is no public clamour to increase limits. It is purely a measure that pampers the fabled 1 per cent.

Yet the program also helps lower-income Canadians who are able to save. It shouldn’t be scrapped. It should be fixed.

Some simple — and fairer — solutions are within reach.

One option is to put a lifetime limit on TFSA contributions — say $150,000. That figure represents roughly 25 years of contributions at the current annual maximum of $5,500, and would be more than adequate for most Canadians.

Then place a lifetime tax-exempt limit of $450,000 on each TFSA holder, which would allow for a three-fold gain in value. That ceiling is 46 times higher than the median financial assets of Canadian households in 2012.

Finally, since TFSA incomes are not counted in considerations of income support eligibility, minimize the scope for tax dodges by setting a hard-and-fast income threshold at which Old Age Security benefits are clawed back ($72,809 in 2015). This number would apply to the “total income” line of the tax return, rather than the more malleable “taxable income” line, as is presently the case.

The bottom line is that the government needs to apply more brake and less accelerator to TFSAs. If not, it risks steering us all into a fiscal ditch from which we will not easily escape. Let us hope that is not the very point.

An abridged version of this article was published in Hill Times magazine.

Armine Yalnizyan is Senior Economist at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. You can follow her on twitter @ArmineYalnizyan.