There’s growing alarm over rising debt levels in Canada, but by just looking at household and government balance sheets, a big part of the picture — and the solution — is being neglected.

The Globe and Mail has published a week-long series called, “Debt: Canada’s borrowing binge,” that’s heavy on alarm, but short on solutions. And certainly the situation appears alarming.

- Total debt of Canadian households rose to $1.8 billion at the end of last year, almost as much as Canada’s annual economic output (GDP), more than $50,000 for every man, woman and child in the country.

- Household debt rose to a record 165.6 per cent ratio of household disposable income at the end of 2014, higher than in the US just prior to the financial crisis.

- Paying for these higher debt loads may be manageable now with low interest rates, but just a one percentage point increase in interest rates would increase monthly payments by about 10 per cent on a typical mortgage.

It is important more attention is paid to capital and debt, especially since we are still suffering from the aftermath of what was a “balance-sheet recession” and because economics has been overly focused on income measures for too long. As I wrote in the Globe a year ago, “If growing imbalances of capital, household debt and corporate surpluses had received greater attention more economists might have foreseen the recent financial crisis.”

But all the recent handwringing over rising household and debt levels ignores one critical point: any one person’s financial liability is someone else’s financial asset. Across all the sectors in the economy (households, corporations, governments and non-residents) in the national balance sheet, net borrowing and lending all balance out to zero.

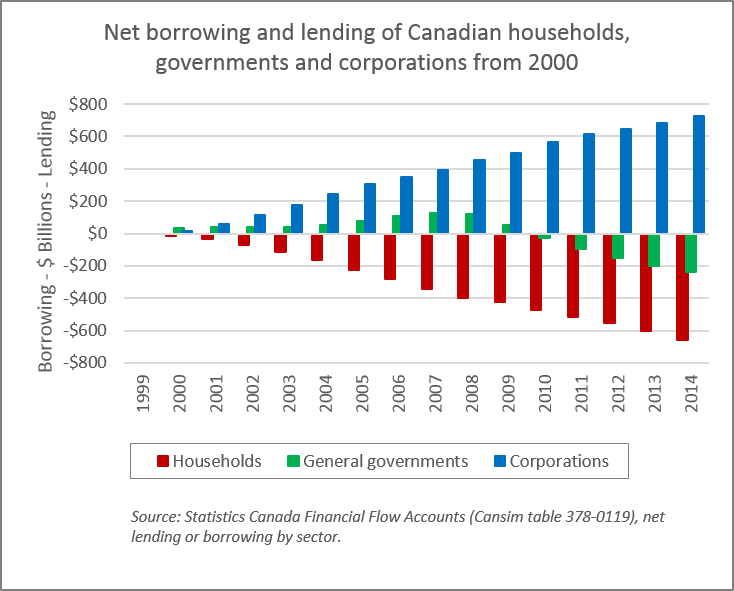

The rising income share of the top one percent has been startling (and also echoed in increasing imbalances in debt and wealth by income and generation) the shift in net borrowing and lending between the household and corporate sector is just as dramatic, and reflect almost perfect mirror images of each other.

For decades until the mid-1990s, Canadian households were net lenders to corporations and to governments. Since then, with low wage increases and rising house prices, households have increasingly gone into financial debt, borrowing an additional $706 billion since 1997 — an increase in net borrowing to the tune of about $50,000 per household. Meanwhile, with high profits, low taxes and low rates of investment, Canadian corporations have built up ever larger surpluses. They’ve become net lenders to the tune of $730 billion since 1997, with non-financial corporations accumulating $675 billion in cash.

Canadian governments ran surpluses and reduced their overall debts from the late 1990s to 2007, then ran deficits following the economic crisis — although those are now shrinking. Non-residents (significant investors in government bonds) demonstrate a bit of a lagged mirror image to the government balance: net lenders when governments are borrowing and vice versa.

What these national balance sheet figures show is that while government deficits and debts get a lot of media attention, they’ve been dwarfed by changes in the balance sheets of households and corporations in Canada. Government debt/GDP ratios are declining again, while the debt ratios of households have kept on increasing. Cuts to public sector wages and to public services reduce incomes and increase costs for people, which make the household debt situation worse. And if households cut back on spending, that slows down the economy, making government finances worse.

McKinsey’s recent report on global debt (page 20) shows that Canada has the 2nd greatest imbalance between household and corporate debt of 14 advanced economies. Debt of Canadian non-financial corporations as a share of our economy is the second lowest of these 14 countries, while our household debt is the fourth highest. Our ratio of household to corporate debt at 153 per cent is a close second to Australia and far above any other country.

The solution is clear: we need to rebalance our national balance sheet. The imbalance in our national balance sheet won’t be fixed until corporations are pushed to do something with their surpluses: invest in the economy, distribute to shareholders and/or pay workers more. If they don’t, our governments should increase corporate taxes and used the increased revenues to invest in the economy, improve public services and reduce the financial pressures households are dealing with — and help alleviate our real debt problem.