A recent media release from CIBC said the newly announced higher contribution limits for Tax Free Savings Accounts were prompting 27 per cent of Canadians to save more.

That’s startling news, if true. Just how reliable are statements like this?

They come from an Angus Reid Forum poll of 3,000 Canadians, conducted just days after the federal budget announced the long-promised — and widely criticized — changes to the TFSA.

The majority of respondents were aware the newly increased contribution limit is now $10K. In fact, four per cent of respondents had already socked the money away in their accounts.

But a third (34 per cent) said they didn’t have enough money to contribute this year.

Most of these economic “facts” I found hard to swallow. You should consider taking a grain of salt with them too. That’s because they don’t square with what Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) and Statistics Canada findings about how TFSAs are used, and how Canadians save.

First, let’s look at the headline news: 27 per cent of Canadians say they’ll be saving more because the new, higher contribution limits support their savings plans; they’ll be saving more.

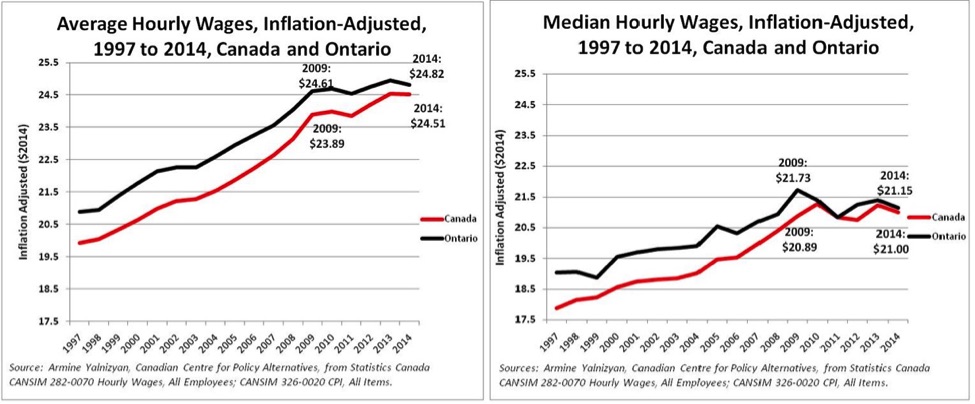

Fact check: Canadian savings rates have been falling every year since these accounts were introduced in January 2009, in the heart of a recession. That’s rational. Savings rates have fallen alongside interest rates, which are now lower than in the 1930s. It’s a great time to pay off debt, or acquire big new purchases that require borrowing. It’s not a great time to save. Savings rates also aren’t rising for most Canadians because incomes aren’t doing much. We haven’t had an update of annual income data since 2011 (see rant below) but average hourly wages have barely beat inflation since 2009; median hourly wages are lower than in 2010, adjusting for inflation.

Second, according to the poll’s findings, only a third (34 per cent) of Canadians are not contributing because they don’t have enough money, just slightly higher than 27 per cent of Canadians who don’t have a TFSA.

Fact check: CRA says almost 60 per cent of Canadian tax filers don’t have a TFSA. That’s the most recent estimate available, based on 2013. (<Rant alert> We have 2013 TFSA stats, but have to estimate the number of 2013 tax filers based on growth from the past few years, because CRA hasn’t published any final income tax statistics beyond 2011. We only have preliminary stats for 2012. Hopefully these data, which usually take 18 months after the end of the calendar year to process, will be published soon after the federal election in October. <End of rant>)

Finally, the only statistics from the poll that weren’t totally out of whack was how many Canadians are maximizing the contribution limits in their accounts. The poll found that 4 per cent of respondents had already socked away the new maximum limit, and that 10 per cent of respondents said they typically contribute the maximum and will do so under the new limits.

Fact check: Revenue Canada’s statistics show only 7 per cent of Canadians tax filers had maxed out their contribution room by 2013 (and an even smaller share of Canadian households, since many of the “maximizers” are from the same family). The proportion of those able to contribute to the maximum limit fell each year from 2009 to 2013, and that’s before the annual limit doubled.

So the fact that 10 per cent of poll respondents self-identified as “maximizers” was the only part of the story that roughly square with the facts as we know them. The other stats are completely unreliable indicators, and should be cited and repeated with far greater circumspection by media.

It’s worth asking how polls get results that are so out of line with reality. The answer: it depends on who’s being asked, and what they’re being asked.

Those 3,000 people polled in the Angus Reid Forum are a regular panel of people who opt-in to do surveys that are emailed to them from Angus Reid several times a month. To remain on the panel they have to complete at least one survey a quarter, for which they get paid (a handsome $1 to $5 a survey).

A huge non-response bias shows up in these stats, when using Canada Revenue Agency and Statistics Canada statistics as the point of reference. Judging from the answers, the people on this panel are more like the country’s TFSA maximizers than the majority of Canadians, who simply disappear from the story.

Apart from their personal attributes, survey participants are asked to agree or disagree with leading statements like: “I will try to increase my contribution above $5,500″. (The response to this statement provided the headline — “Higher TFSA limit prompts one-quarter of Canadians to save more,” echoed by some news outlets.)

Will I try to increase my TFSA contribution above $5,500 this year? In the absence of other factors, of course the answer is yes, I’ll try to save more. I’ll also try to earn more, and spend more time with my kids.

Frankly, these polls are not really about fact versus fiction. They’re more about aspiration versus reality.

I called up CIBC to test my theory. I asked the spokesperson for this survey why they conduct such polls, knowing that their “facts” have little relation with official ones.

They acknowledged the differences and said they use surveys as a way of understanding what their clients would do if they could (emphasis added), so the bank’s managers and advisors can help them reach their financial goals. Kind of like high school counsellors.

That’s nice. But let’s be clear.

Banks benefit from advertising the TFSA — more deposits, more fees — and polls like this give them an excuse to publish some fresh numbers, and get themselves and their products in the headlines.

There’s nothing wrong with polling, but both media and decision-makers need to view them as providing more truthiness than truth.

Sadly, though, poll-generated numbers are often trotted out to produce a veneer of quantitative objectivity that justifies next steps. They can create circular logic.

Two days after the CIBC media release came out, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance was meeting to discuss C-59, the Act to implement the budget. Some witnesses pointed out the new, higher contributions limits for the TFSA exacerbated income inequality and undermined public finances over the long term, points made for months by a broad cross-section of Canadian economists across the political spectrum. The proposed amendment to the Act that could offset these trends — introducing lifetime limits on contributions and growth of assets in accounts — could easily be waved off by someone pointing to these “statistics” and suggesting that the higher contribution limits “work,” because more Canadians are planning to save because of them.

The line between truth and truthiness in economic statistics is getting easier to miss. That’s a problem because it helps evidence-based decision-making become decision-based evidence-making.

Armine Yalnizyan is Senior Economist with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. You can follow her on Twitter @ArmineYalnizyan.

This blog post is based on Armine’s business column for CBC Radio’s Metro Morning, which aired May 27, 2015.