Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Elites and the talking heads in the media are arguing about how to respond to Canada’s soured economic outlook. Who should try to boost the economy: the federal government via fiscal stimulus or the Bank of Canada via monetary policy? But while elites argue amongst themselves, the overriding context is a transfer and concentration of economic power upwards. This, not $10 billion here or 0.25 per cent there, is what hamstrings any policy response going to the benefit of the many.

First, some context. Last week’s report from the Bank of Canada describing the state of the economy did not make for happy reading. While there is no crash, no panic and no crisis, the picture isn’t particularly rosy. The kind of generalized malaise and stagnation that has affected much of the globe since the last crisis — and that our resource boom staved off — seems to be hitting home. The Bank revised downwards its projections for both growth and inflation, and has a history of being overoptimistic.

As the big drop in the price of oil is looking more and more long term (and actually coming back to what it has been in inflation-adjusted terms in the very long run), other parts of the economy have not yet picked up the slack. More Bank of Canada analysis released last week, focusing on the impact of cheap oil, said as much. Here’s the headline chart showing a projected long negative adjustment to lower oil prices across the whole economy, beyond just the oil provinces:

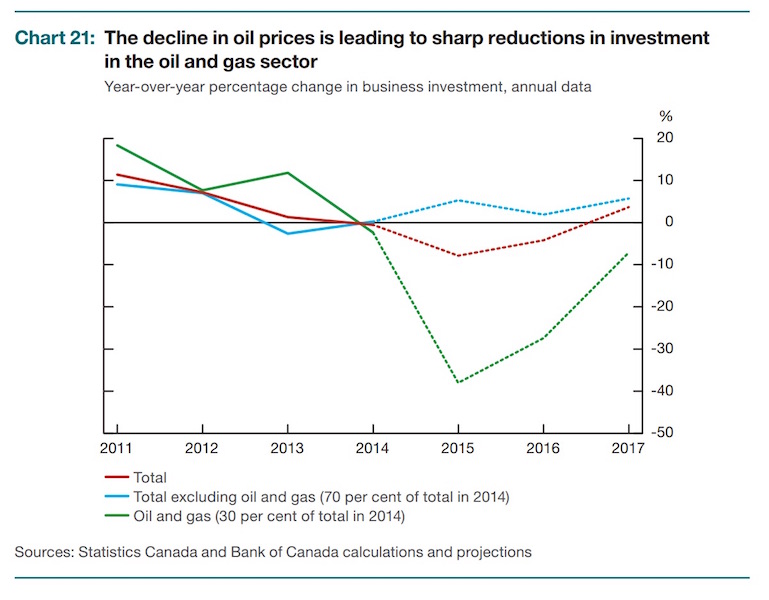

Here, for one more example, are investment projections broken down between the oil and gas sector and the rest of the economy:

In plain language, the resource boom has left some deep scars in other parts of the economy. Exporters of goods and services aren’t quite picking up the pieces after the oil producers who are today selling oil for less than the barrels it’s shipped in. In the meantime, all of us just took what is effectively a sizeable wage cut as the Canadian dollar has fallen sharply along with the price of oil.

So if that’s the diagnosis, where is the argument over what to do about it? Oddly enough, it’s the Bay Street financiers who are pushing the new Liberal government to spend, and spend more than promised. Not only that, with less trust between themselves, the banks are helping make the alternative, monetary policy, less effective than it would otherwise be.

Anytime Bay Street calls for more government spending, we should at least be asking one question: why? Is it because the private sector isn’t investing enough on its own? That is surely part of it. With rising excess capacity, less appetite for private investment in decimated export industries and lots of global uncertainty, government can take on risk and provide some minimal returns with debt-financed spending.

Is it because government investment can be channelled to where it will serve profit opportunities best? This too is the case. After decades of neoliberal restructuring — away from public housing to mortgage guarantees, away from EI payments to more insecure work, away from industrial policy to free trade and away from truly public services to a more subcontracts and public-private partnerships — the conditions have rarely been better for big business and finance to get a helping hand from the government.

The opposite argument says that while Canada is a small, open economy so and much of how our economy adjusts happens through the gyrations of our dollar. That more spending that boosts the economy somewhere will lead to contraction elsewhere. Regulating the economy in the interests of business — opening it up for money and closing off opportunities for people — has made this more likely. And it’s not that monetary policy has been ineffective: the U.S. quantitative easing (QE) program, and to some extent those of others, has shown as much. There is no doubt it helped rescue the economy from crisis in 2008. At the same time, one of the overriding concerns of the U.S. Federal Reserve hasn’t changed: to keep a cap on wage growth, leaving the fruits of the meager recovery flowing upwards. Monetary policy has helped avert crisis elsewhere — but one also a recovery heavily biased towards elites.

This then is the false bind faced by elites and the very real one faced by the rest. The broad effects of fiscal policy may be dissipated away, but monetary policy in its current form keeps driving crisis-prone, debt-financed consumption for regular people and higher-asset values (stocks, houses, art and other baubles), therefore bigger fortunes, for the wealthy. And remember that wealth inequality in Canada has grown (doubled by some measures) since 2000.

Trying to pass as a rich debate, this argument merely demonstrates the poverty of response to economic malaise. The structural bounds of “realistic” policy options are more than ever apparent, represented here by the “natural governing party” Liberals the same way someone like Hillary Clinton, the millionaire’s favourite, represents them in the U.S.

There are alternatives. Canada needs public investment to be sure, but who will benefit and how? Could we retool the shuttered or shuttering factories of Ontario’s rust belt to create high-speed rail and build a link between Calgary and Edmonton? Could we re-invest money and change the rules for unemployment insurance so that those losing their jobs in Alberta don’t have to look for first available crappy job or leave their families like those in the Maritimes did for work in the oil sands?

A recent article in Maclean’s argued that Alberta and its oil industry don’t need a bailout because southwestern Ontario has suffered more with less bailout money. The industry certainly doesn’t need a bailout and, yes, Ontario’s manufacturing heartland hasn’t seen much help, shedding factories and jobs to global competition and supply chain restructuring. It’s easy to pit people against one another, but there is a common thread from Ontario in the 2000s to Alberta today: an economy that disregards workers and regular people while helping to drive our planet further into ecological crisis.

Ontario boomed on cars, and then Alberta boomed on oil. Both were marks of an irrational economy and both busts have hit workers hardest. Ontario saw a toxic brew of layoffs and shutdowns from the private sector mixed with slow but steady austerity from successive provincial governments. Alberta may yet see the same given the paltry bounds of acceptable policy.

Take a look at the bailout of GM after the 2008 financial crisis. Ottawa bought shares (stimulus) and made a tidy profit on them but this had no effect on the restructuring still ongoing in Ontario. This amounts to playing the same short-term gain game as the private sector. A big stake could have been used influence corporate policy, to start to re-enact industrial policy and to reactivate a region.

Or take what has happened to EI. Today, over six in 10 of the unemployed do not see any benefits to help ride over the rough times. This forces people into bad jobs quickly, further driving down standards for everyone and leaving no time for retraining, for instance towards green jobs. This is an old-school kind of precarity. Investing in simple, public unemployment or retirement insurance schemes helps fight this kind of precarity, leaving us less at the mercy of employers.

Talking heads for and against talk about fiscal stimulus “shovels in the ground,” a kind of bastardized Keynesianism that ignores the loss of power on the part of the majority. As the elite discussion over the future of policy grabs the big economic headlines, we also learn that 78 per cent of Ontario employers are breaking basic workplace rules and protections.

So while policy elites care about interest rates, your boss cares about the length of your lunch break or skimping on safety at work. It’s a neat package. Policy debates over “the economy” are important, but this basic, workplace-level injustice shows just why we have to rebuild power from the bottom up and how far there is to go.

When the options from the commentariat are “grin and bear it,” “help us get richer by driving up asset prices and your debt” or “give us fat contracts to build things,” it’s easy to lose track — and lose hope. Let’s remember that the economy isn’t some separate special part of the world, and especially not one that works by some special set of rules always rigged by elites against regular people. As we look set to join the club of global economies mired in stagnation and inequality, there is no point wasting time in getting started turning the economy around in our favour. Elites will keep trying to leave this bust better placed to get the most out of the next boom. We shouldn’t let them get away with it.

Originally posted to my blog here.

Photo: Norris Wong/flickr

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.