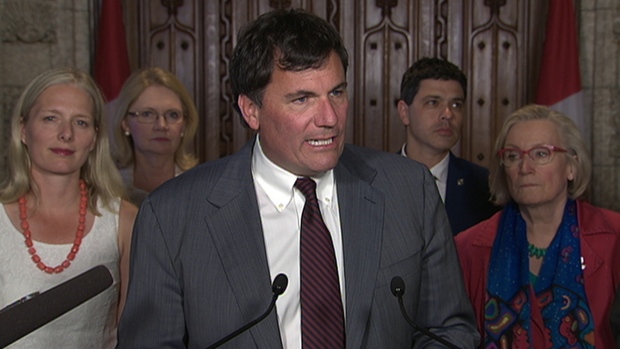

No less than six cabinet ministers stood in the foyer of the House of Commons yesterday to announce sweeping reviews of key environmental laws. The details are not clear yet — in fact, the government has (perhaps wisely) asked for public input before it finalizes the review processes.

It is clear that there is an opportunity to not only undo the damage that the Harper government had done to environmental assessment and the protection of fish and fish habitat, but to go much further and fundamentally change our approach to environmental planning and industrial development.

The federal government has announced that the Fisheries Act and the Navigation Protection Act will be reviewed by the relevant parliamentary committees once Parliament resumes sitting on September 19, while the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act and the National Energy Board Act will be reviewed by independent panels. The various reviews will have to be coordinated since these laws are quite closely related. The ministries involved are:

- Fisheries and Oceans

- Environment and Climate Change

- Transport

- Science and Innovation

- Indigenous and Northern Affairs

- Natural Resources

Perhaps wisely, the government did not announce the panels themselves, but rather opened a 30-day consultation with the public before it makes any final determinations on the panels’ mandates and membership.

Comments will be accepted until July 20. Once they have been named, both expert panels will travel the country and “consult broadly with Indigenous peoples and the public,” reporting back in early 2017. Their recommendations will then feed into the legislative process, as new legislation will have to be drafted and reviewed before becoming law — prior to the next federal election in 2019.

In addition, the panel reviewing the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act will receive advice from an expert “multi-interest advisory committee” made up of Indigenous, industry and environmental group representatives.

Thirty years after the Brundtland Commission report, decision-makers in government and industry still struggle with the concept of sustainability — but reality has overtaken them; green economies are quietly leaving extraction and exploitation behind.

While business leaders and politicians still talk about “trading off’ jobs and the environment in destructive development, more jobs are being created in more sustainable fields like alternative energy, where economic development actually helps the environment.

We finally have an opportunity to catch up, and build an environmental assessment framework based on sustainability rather than just “managing and mitigating” environmental destruction and human harm — a “next generation” of environmental assessment, or better yet, sustainability assessment.

We’re obviously excited about this possibility, but we’re also very concerned that this opportunity not be lost — or stolen by industry groups focused only on short term profit, who still have massive political clout.

The review process has to reflect the incredible advances in the theory and practice of environmental and social impact assessment over the past couple of decades, but it also has to respond to the very real concerns of the public. It also has to acknowledge the place of Indigenous peoples in implementing their own decision-making processes under their sovereign right to free, prior, informed consent, recognised by the federal government through the United Nations Declaration on Indigenous Peoples.

We’re also deeply concerned that the government is essentially allowing the status quo to continue until new legislation is in place. No projects will be deferred, and the “interim measures” that the federal government introduced in January for pipeline reviews have been panned as inadequate, unclear, and unaccountable.

While Elizabeth May has pressed to simply repeal the Conservatives’ 2012 Bills C-38 and C-45, this would have thrown work on the reviews back to agencies like the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, that no longer have the staff expertise and capacity to do it – also thanks in large part to the previous Conservative government.

Nonetheless, if the government is serious about “rebuilding trust” in the process, it will have to take a much more cautious approach. It may seem to add dreaded “uncertainty” for proponents and investors, but let’s be honest — there’s precious little certainty already, whether in the markets and project finance, or in getting government approvals that aren’t worth the paper they’re printed on.

Even industry proponents who quite like the existing system have recognised it doesn’t work. They can get permits to build their projects, all right, but they can’t get a “social licence” because the public and Indigenous peoples — having been essentially cut out of the review process — won’t allow them to proceed, whether by legal action or direct action.

There are some very obvious basic steps that need to be taken, such as getting the National Energy Board and the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission out of the business of doing public reviews, which they clearly can’t do, and focus on doing whatever it is that they’re good at. (On the other hand, they both suffer from incompetence and industry capture, so maybe they should just focus on learning how to do basic regulation).

But we have before us something much bigger. Whether for the sake of public credibility, scientific integrity or respectful relations with Indigenous peoples, an ambitious and visionary redefinition of environmental impact assessment for Canada is more than an opportunity at this point. It is a necessity.

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.