Fidel Castro stands in a long line of great socialist leaders who betrayed socialism. The list pretty well includes all of them, from Lenin, Trotsky and Stalin, to Mao Zedong and Chou En-lai, to Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, to Mengistu in Ethiopia.

In the name of the beloved masses, these revolutionaries became the greatest mass murderers in history, responsible for genocide, famine, incalculable suffering, widespread torture and the deaths of tens of millions of workers for the crime of somehow displeasing their great leader.

Castro was not a mass murderer of the same order, though hundreds, maybe thousands, of opponents were executed in the early years. He also broke the hearts of the millions of Cubans who welcomed his revolution.

In reality, the dictator led a nation with an economy frozen in the 1950s, captive of the Soviet Union on which Castro foolishly made his tiny island dependent. Nor was it all the fault of the idiotic American boycott, as Castro apologists are quick to insist.

Scarcity became the overriding characteristic of Fidelismo, scarcity in both the quantity and quality of the life he provided. Dissent was not tolerated, political dissidents imprisoned, human rights a foreign intrusion, free speech counterrevolutionary, trade unions government servants, gays an insult to the revolution. So did Cuba’s president-for-life serve his people, to use Justin Trudeau’s immortal words?

Yes, the revolution massively advanced health and education. But it also suppressed independent thinking. Critical needs like public housing and public transit were not met.

Yes, the Cuban revolutionary army played a critical role in Angola and hastened the death of apartheid. But it also bolstered the murderous “Marxists” of the Derg in Ethiopia.

As everyone who ever went to Fidel’s Havana almost immediately learned, one of the great contributions of the revolution was a large ice-cream shop nestled in a downtown park, always jammed with eager customers who seemed used to standing in line for over an hour, maybe much more, to get a cone on a tropical day. This was the government-owned Coppelia ice-cream parlour, at which foreigners — especially leftist tourists anxious to find evidence of the new utopia Castro was building in the midst of the exploited Latina Third World — all ended up sooner or later.

In truth, the evidence was scarce of a new successful socialist Cuba, so Coppelia saved the day. That this was the best that Fidelismo had to offer the proletariat after decades in power was a sad irony his fawning foreign admirers rarely cared to conjure with.

My first visit was in 1968, at exactly the moment the Soviet Union was busy crushing the Prague Spring. After months of political liberalization in Czechoslovakia, in August the U.S.S.R. invaded to brutally put down the insurgency. There was no doubt in anyone’s mind what Cubans made of this. It was impossible not to see the parallels. Mighty Washington had been trying to murder Castro and destroy the revolution for years. So despite the Moscow-Havana alliance forged by Castro, Czechoslovakia was to the Soviets as Cuba was to the Americans, a pest to be crushed underfoot for demanding more independence.

Yet for many days after the invasion, Cuba’s media — strictly government controlled — carried not a word. Everyone was mystified. But in Castro’s Cuba, you learned what Fidel wanted you to know when he wanted you to know it.

Finally, word came that Fidel was going to hand down the definitive Cuban response. I watched his speech in a public bar with a crowd of Cubans. In no time the sense of shock and disappointment in the room was palpable. Even with my few pitiful words of Spanish I knew exactly what was happening.

Fidel had sold out the revolution again. He simply repeated Moscow’s line. Prague’s spring was no attempt by a small nation to liberate itself from its cruel imperial master. This was a benevolent Soviet Union putting down the insurrection of a reactionary remnant of the Czech ruling class. Everyone soon left the bar, in silence. El lider may not have seen that he had sold his soul to the Kremlin. The masses sure did.

While I was there being deeply disillusioned by the revolution, I took the opportunity to join the rest of the nation in something quaintly called trabajo voluntario. This was volunteering to cut sugar cane, a compulsory activity for all. I joined an early-morning labour gang and was driven out to the sugar fields and given my heavy machete. It again took little effort to understand that there was great discontent among the glorious masses about this obligatory voluntary program.

Among other things, it was back-breaking work. Or at least arm-breaking. Within 20 minutes of slashing away at the cane stalks, my arm was paralyzed with unbearable pain. I could literally not move it, and was forced to stop. My companeros continued all day, while my arm remained immobile and excruciatingly sore for several weeks. Suffering for the cause, someone said.

I went back to Cuba a few times. Once, in a run-down, almost-empty bookstore in a town near the tourist beaches, I came across the entire collected works, in Russian, of one of the old Bolshevik leaders, possibly Bukharin, written before Stalin had him murdered. I probably could have had all 18 volumes for two bucks but I saved my capitalist acquisitiveness for another rare treat at Coppelia. Viva Fidel! Viva la revolucion!

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

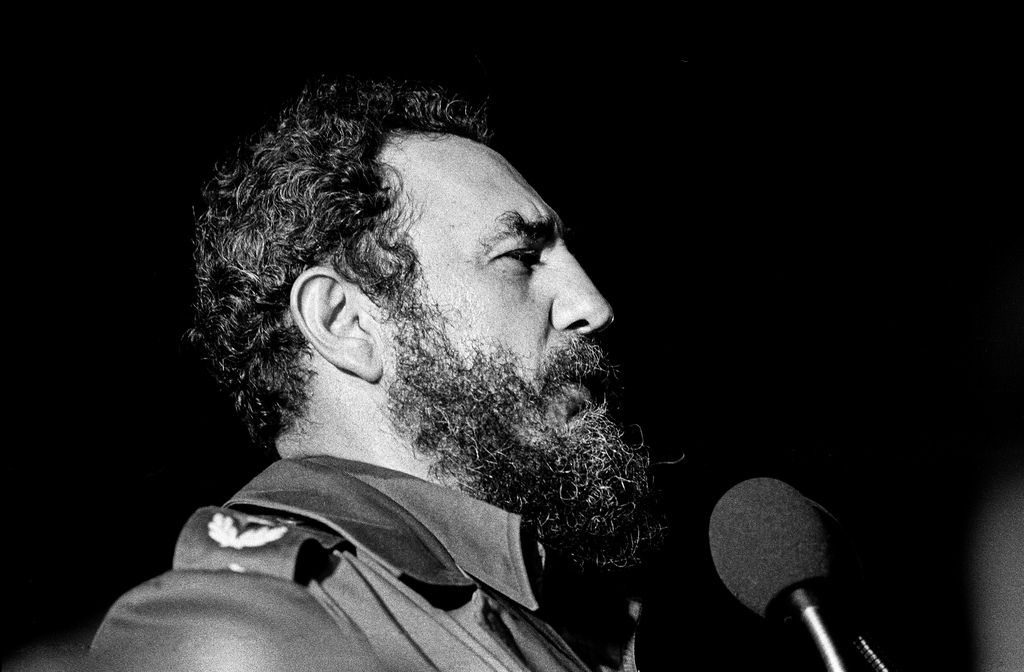

Image: Flickr/Marcelo Montecino