An engineering professor, a halal grocery shop owner, a civil servant and father of four. These were among the six men gunned down by a French-Canadian nationalist in a Quebec City mosque on Monday evening.

Police reported that 19 people were also wounded during the evening prayers at the Centre Culturel Islamique de Québec (Quebec Islamic Cultural Centre) and that all the men killed had ranged in age from 35 to 70. Thirty-nine people escaped the mosque without injuries.

“We’re not talking about a war zone here, we’re talking about Quebec,” Samer Majzoub, the president of the Canadian-Muslim Forum and a resident of Montreal for 28 years, told Middle East Eye.

“We feel unsafe now. Whether we like it or not it has created a lot of fear in the minds of people… like how did the suspects buy a gun? We’re not in the U.S. where you can just buy one from a convenience store.”

The Islamic centre is situated near Quebec City’s Laval University and attracted many students to its prayer services, he added.

“I have been getting messages from parents all morning asking whether they should send their children to school,” Majzoub said on Monday morning. “We told them ‘go ahead.’ We cannot surrender to terror and panic.”

In the aftermath of the attack, one of the worst ever on Canadian soil, Muslims across Quebec said they felt fearful on a level they had never experienced before. Sayeeda Alibhai, who has lived in Montreal for 42 years, said she was shocked to find armed security guards in front of several mosques she drove past on Monday. “I keep getting visions of it happening to my local mosque, or any of the other ones,” she said.

The sight of armed security officers outside of places of worship is far from typical in Canada. One Islamic school and community centre north of Toronto alerted parents that extra safety measures had been taken, including meeting with local police officials and hiring an additional private security guard.

“In light of the recent events in Quebec, we certainly understand parents concern for the safety of their children,” Marcello D’Agostino, principal of As-Sadiq Islamic School said in an email circulated to parents on Monday afternoon. “Please know that the school is doing everything possible to ensure the safety of our children.”

“We thought Canada was safe”

Canada’s newcomers — the Syrian and Iraqi families who entered the country last year — were also shocked. Vian, a 17-year-old Yazidi boy who recently relocated to Toronto from Iraq, told Middle East Eye he and his family feel “very confused” about Canada now. “We thought Canada was safe. I am very sad about this because I felt like this when I was in Iraq.”

“You know first-hand how bad it is when someone kills,” adds his mother, Fatima. “We lost a lot of things when we came to Canada, just to come to a safe country. In Turkey we had a lot of problems but when we came to Canada, we felt like nothing had ever happened to us. We forgot all about our past. Now when we hear about the things that happened in Quebec it hurts us.”

For many, the prime minister’s words in Parliament caused the greatest stir — and comfort — in the aftermath of the attack.

“We are with you,” Justin Trudeau said, addressing Canada’s one million Muslim citizens directly. “Thirty-six million hearts are breaking with yours. Know that we value you. You enrich our shared country in immeasurable ways. You are home.”

Tellingly, he described the shooting as a “despicable act of terror” committed against Canada and all Canadians.

It was a choice of words not lost on Muslims living in North America, where mass shootings are often selectively classified by the mainstream news media as terrorist acts — seemingly on the basis of whether the perpetrator is Muslim or not.

“His words were very reassuring to hear,” Fariha Naqvi, a marketing executive based in Montreal said. “That’s a narrative that’s extremely important. So many Muslims have watched incidents across the world where they’re not always called terrorism. Prime Minister Trudeau has renewed our faith in the Canadian system.”

Randall Hansen, a political science professor at the University of Toronto, agreed. “The prime minister’s move sends two messages: One, to Islamophobes, that terrorism doesn’t emerge from any one community — but more fundamentally — how we classify something as criminal or legal is a very political decision that can demonize particular minorities.

“Secondly, it sends a message to Muslims that any attack or murder is by definition an attack regardless of whether it was committed by a Muslim or not. “

The Trump effect

But Canadians were divided as to whether the attack had more to do with newly elected U.S. President Donald Trump’s rhetoric on Muslims, or on racial and religious tensions that existed in Quebec long before Trump’s advent in U.S. politics.

While Hansen believed the responsibility of “whipping anti-Islamic sentiments” could only lie with Trump, Montreal residents felt otherwise.

“When the flames of hatred are blowing this side of the border it is natural to point the finger at President Trump,” said Naqvi. “Having been born and raised in Quebec I know that’s not the full reason.”

She cited the controversial proposed Charter of Values, introduced in Quebec in 2013, which would ban public employees from wearing religious items, among other changes. “There’s a lot of Islamophobia that culminated because of that,” she said, adding that her first brush with prejudice came during a time when she was called a terrorist while on a visit to the theatre with her daughter.

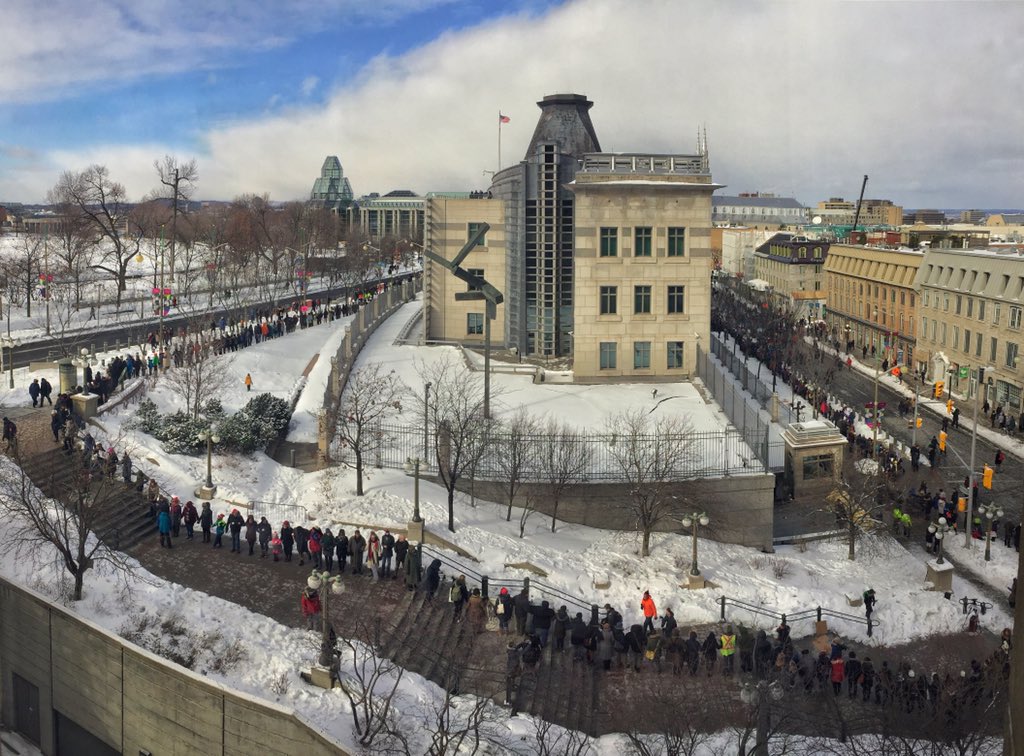

Candlelight vigils to mourn the six men were held across most Canadian capitals on Monday evening. Several churches and synagogues also publicly expressed their solidarity, including one church in the province of Nova Scotia whose signboard read: “We preach love and respect for all. Today we are Muslim.”

This article originally appeared in The Middle East Eye.

Like this article? Please chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Image: Twitter/@pannetonc