One-in-four people living on a First Nations reserve may not have clean water.

In another context, one could assume such a headline would be in relation to the world’s developing nations — with rock stars and celebrities gathering together to produce a donation song to improve the impoverished conditions. I could even double-down and claim that many people would not even be able to name a country in the affected part of the world.

So it’s a huge embarrassment that there are actually communities within Canada that don’t have access to clean water, a human right.

This is how racism shows its ugly head in Canada.

It’s what I’ve come to call Attawaspikat or Elsipogtog syndrome: the farther away a community is from the centre of Canadian power and the higher the concentration of Indigenous members that live in the affected community, the less likely the media and public consciousness will focus on that issue.

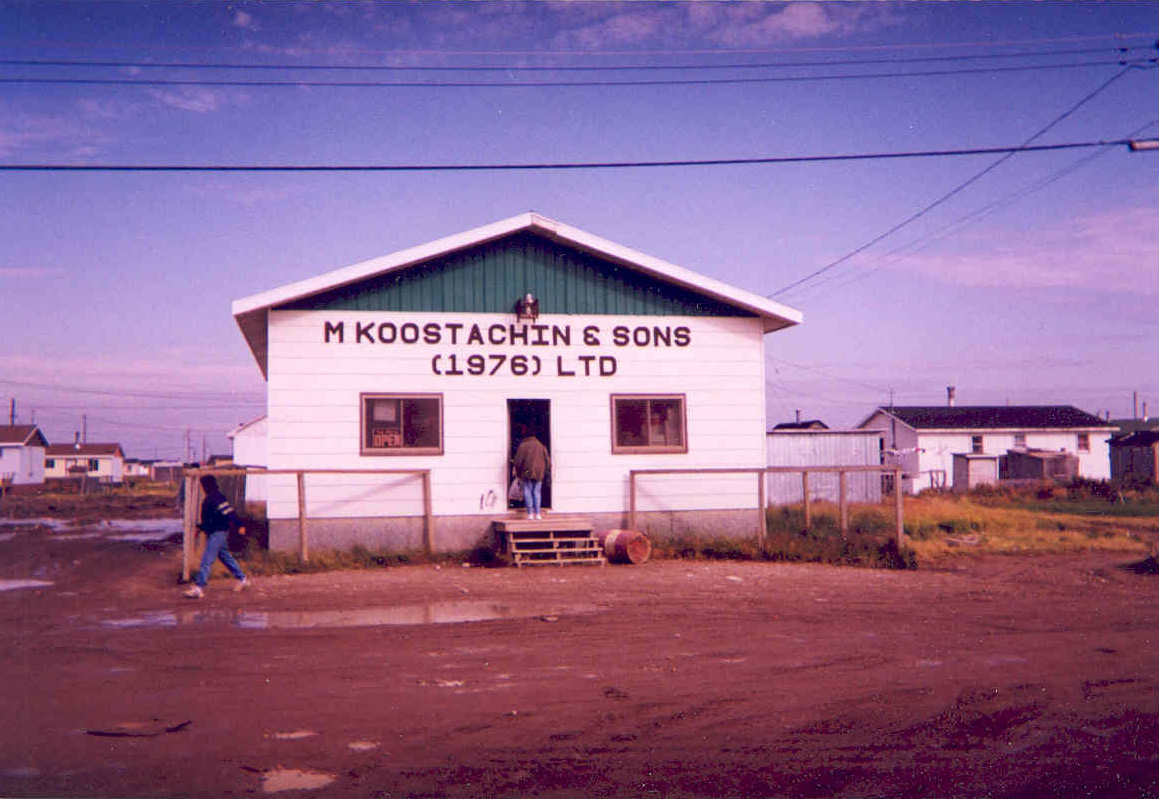

We can see the same “distance and racism” issue in the lack of reaction to the ridiculously high-priced food found in stores in Northern communities, or the likelihood that an Indigenous woman will go missing on Northern B.C. highways.

Usually, like in Elsipogtog, Canada’s racism is evident in the mere fact that most reporters don’t bother asking how to properly pronounce an Indigenous community’s name.

I also had to correct a union speaker at an anti-racism rally in downtown Toronto. I was forced to resort to the old Occupy “mic-check” to even get the attention of maybe 100 people at the rally. After I finally got his attention, I reprimanded him for not taking the time to ask one person how to properly pronounce the community’s name while yet speaking on behalf of that community. It took a lengthy call-and-response game between him and the crowd to resolve the issue.

These are important lessons that need to be learned, because just like water rights and human rights are linked, dignity and agency are also connected.

I apologize for digressing here, but it’s these types of racism even within our own activist communities that must be resolved if anyone thinks they can take the high ground when denouncing, for example, Ezra Levant. And if we understand this kind of racism, we can stop it.

And we can stop the ignorance that is partly to blame for the lack of water rights in First Nations communities.

According to a recent report by of Health Canada and B.C.’s First Nations Health Authority, their data highlights that up to one-in-four people may not have clean drinking water on First Nation reserves.

Drinking water advisories (DWA) should not be a way of life in a country with an abundant water source, but it’s a lack of infrastructure, a lack of political will and a lack of public solidarity that causes such problems.

Especially since the federal government in 2016 released a statement promising to end long-term drinking water advisories, especially affecting Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) funded public systems on-reserve within five years.

According to the Council of Canadians, “some DWAs have been in place for decades. Eleven DWAs in four First Nations — Neskantaga (ON), Shoal Lake No. 40 (ON) as well as Alexis Creek (BC) and Algonquine/Kitigan (QC) — have been in place since 1995, 1997 and 1999, respectively.”

We should be shocked and ashamed of ourselves.

We must look for solutions, including working with our Indigenous allies to highlight the communities that might need public support to finally have access to clean water which might even include getting together to lobby Ottawa.

Unfortunately, we can’t just wave our hands in glee because Stephen Harper is no longer in power, since Justin Trudeau doesn’t seem particularly motivated to fix these DWA situations. Because on top of these long-standing DWAs, the Trudeau government has actually approved a series of development projects that threaten important waterways such as Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain Expansion project and Enbridge’s Line 3 tar sands pipelines replacement project.

The Site C mega-dam is also a major concern for environmentalists and Indigenous groups in British Columbia right now, as is TransCanada’s NOVA Gas pipeline, which will transport fracked gas from northeastern B.C. to Alberta.

Thank goodness that there is a beautiful culture of resistance in B.C., and amazing moments of joint solidarity between environmental and Indigenous communities.

It’s communities fighting to (finally) have DWAs lifted, or fighting to protecting the water of Mother Earth that should guide our way, not the whims of the government. It’s important to not only step up to defend water rights and human rights, but to fight the racism that keeps these communities water-impoverished.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Please chip in to keep stories like these coming.