I Live Here is a rich collection of personal stories gathered from four distinct areas of the world in which the conditions faced by women and children are particularly devastating. Themes of poverty, displacement due to war, sexual abuse, familial responsibility, self-sacrifice, resourcefulness, hope and despair resonate with increasing power as one reads about each region.

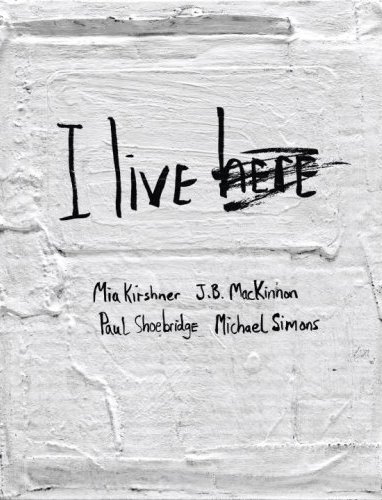

These tales from Ingushetia (Russian Federation), Burma, Ciudad Juarez (Mexico) and Malawi are tied together through the arc of Mia Kirshner’s personal journal entries, which frame the various contributions in the collection — a collection of four separate volumes held in a fold-up cardboard package. Each of the four pullouts is aesthetically quite unique, distinguished by the often exceptional artistic work of contributors like Joe Sacco, Phoebe Gloeckner, Kamel Khélif and Julie Morstad. Despite the range in works, from detailed pen and ink drawings to fabric-based collage, the collections are unified by the motif of the traveler’s diary in which artifacts and excerpts of experience appear roughly taped into place.

Although the initial impression of the books is of a rough and ready assembly, a closer look at the work of former Adbusters designers, Paul Shoebridge and Michael Simons, reveals that there is nothing "rough" or haphazard about the way in which they combine elements in these "diaries." Take, for example, a page from the Burma volume which depicts a boy soldier, drawn in a very childlike style, but collaged with a photograph of a real young boy (wearing underwear and a prosthetic limb), so that the top half of the drawing joins the bottom half of the photograph to create a hybrid picture of the boy. These elements are roughly cut out and positioned on a background of crinkled grey paper, where they join a tiny toy rooster and prominent red type, declaring loudly in old science-fiction movie-poster font: "I NEVER HAD AN ORDINARY LIFE…."

As a whole, the image is very disquieting, in large part because of the strange, sad-looking image of the small soldier with the prosthetic limb. There is something about the rough, disjointed assembly of the drawn with the photographed that makes the little boy appear even more disjointed and vulnerable. Add to this the delicate, almost precarious quality of the light black and white pencil drawings floating on crumpled paper, and you feel a very strong sense of there being something precious salvaged quickly, and perhaps even surgically, on this page. However, it is the design of the typeface, quoting an excerpt from an interview with the soldier, that presents the most blatant statement of tone and intent in the image. It prevents one from believing it to be part of a traveler’s entry, gathered and assembled quickly on the road, and it speaks most clearly to the designers’ intervention: to their role in defining how the image speaks and to whom. An audience fairly well versed in Western pop cultural references will read the qualities of strangeness and fear expressed in the type. And it is for this audience that the designers are filtering the words of the boy soldier, adapting his drawings, effectively evoking an impression of the boy as a particular character, and depicting his life, or rather his plight, in a jarring and unsettling tone.

While the design is often compelling, certain segments in I Live Here are not as effective as they might be in evoking a sense of character and place. Aesthetic choices, like the use of masking tape for captions, torn and disheveled paper elements, and scotch tape used consistently to visually frame roughly cut or torn excerpts of text sometimes becomes heavy-handed and can overwhelm the compositions and artistic components. This is particularly apparent in the Ingushetia volume, in which the collaged elements are generally not as strong in creating a sense of place and the design does not work as well to integrate the different artistic elements. In this volume I felt that the real standout piece was Joe Sacco’s "Chechen War, Chechen Women," but in some ways it stood out too much from the rest of the volume. It arrives near the end as a hugely informative and emotionally resonant piece but it is unclear how it fits with the other pieces in the volume to create a landscape of experiences. Alone it may achieve this very well, but all the elements in this volume are not well-integrated as in the other volumes.

In "Twenty poems about Claudia," from the Ciudad Juarez volume, the meeting of aesthetic elements — artistic features with narrative and journalistic excerpts and design components — is extremely effective. Here the diary motif works well to promote a sense of something intimate shared. The fabric art, photos, drawings and beautifully composed textual elements trace a strong sense of who Claudia was — one of many vital young women disappeared from the maquiladora areas in this borderland region of Mexico — as well as the world in which she lived. Place and atmosphere are expressed to great effect in this piece and evoke substantial pathos, both for the loss of lives in these communities and for the decline of these communities themselves.

As seems appropriate in a project filled with stories of painful experience, there are many troubling images and grueling passages of recollection and reflection. Pheobe Gloeckner’s "La Tristeza" contains some of the more harrowing images in the collection, all the more remarkable for their captivating technique of seamlessly melding fabric art with photographs into sometimes gory dioramas. But there is also some hopeful, lovelier imagery such as is provided by J.B. MacKinnon’s and Julie Morstad’s "Shatterboy" and, varyingly, by Mia Kirshner throughout her journal entries.

Upon finishing all four volumes of I Live Here, I found myself wanting to go back and re-read long sections, to revisit certain characters and places and to try to understand more about the situations depicted. This must be the lasting value of this collection, published through Amnesty International — that more effectively than the person who stops you on the street or calls you on the phone, the writing, art and design in these volumes compels you to spend considerable time with people and places that are suffering. It succeeds in bringing us the "untold stories" in all their, at times, emotionally shattering detail, but more significantly, it encourages us to want to learn more.–Philippa Mennell

Philippa Mennell is a designer and freelance writer based out of Vancouver, who is currently enjoying the wonders of farm life in Sooke, B.C.