In the past 20 years Canada has seen a few mixed race anthologies that reflect both the time, place and language that we use to talk about being of mixed heritage and the many complicated social locations this takes us to. The first and the groundbreaking, was Miscegenation Blues: Voices of mixed-race women edited by Carol Camper and published in 1991. Ten years later I was fortunate to be part of the editorial team for the journal Fireweed’s issue 75, the Mixed Race issue, published in 2002.

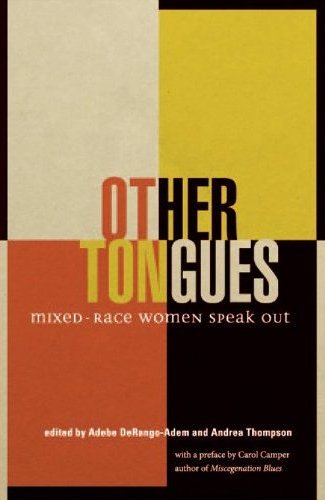

Other Tongues collection of personal essays, poetry and visual art is an excellent addition to the body of writing already out there. In a nice circular way that happens sometimes, Carol Camper wrote the introduction. All these years later, most of the issues are the same, but hearing the experiences of women in their 20s and 30s is heartening, even as they bring sadness and frustration at how little has changed.

The pieces are all short to very short, with the longest piece at around six pages and the average length about two pages long. This is one of the anthology’s strengths as it can show the breadth and range of experiences as well as the vast array of how women have dealt with / coped with / celebrated what their racial identity means to them in the context of Canada and the U.S., where the majority of the contributors live.

There is no mistaking the power of speaking our own stories: having mixed race women naming our struggles within and between our families, who often force us to deny parts that they deem shameful. Whether that’s the parent of colour’s family and existence, or how that’s linked to working class roots, or the naming of one’s identity by others, another continuing theme throughout the collection.

The issue of where mixed race folks are from, where we were born and where we live, are also huge sites of contention, mostly based on what the outside (white) world imagines about mixed race people via badly formed existing narratives. Thus “home” is not always a comfortable place, as it’s often demanded to be proven or justified by the outside, and sometimes denied or hidden within the family.

The anthology is in three sections, by theme. Rules/Roles. Roots/Routes. Revelations.

Erin Kobayashi’s “Pop Quiz” was entertaining and somewhat funny, since I’ve been there and anyone identified as “racially ambiguous” has been there. It was also very sad, and steeped in a resignation, annoyance and anger at being constantly told that we don’t belong and don’t fit into the mono-racial understanding of race and culture that Canada offers.

Naomi Angel’s piece “On the Train” speaks to her travels as a young woman in Japan, her birthplace. She encounters a mixed race family, white American father, Japanese mother and a young daughter. The girl is told by her white father to speak English, when she clearly understands, can speak it just fine and is clearly choosing to speak Japanese.

Angel shares her experiences of not being believed that she was born in Japan, but also her rejection by others when she talks about Vancouver being her home.

In “Mapping Identities,” Gail Prasad tells a story of growing up in 1970s multi-culti Toronto, in which selected students were photographed and had their photos placed on their country of origin on a large map in the main foyer. She had her photo taken, and then was asked where it should go. Her father is from India, her mother from Japan. Since there was already a student from India on the map (and clearly at age eight Prasad already understood the idea of tokenism which is the underlying value of multiculturalism) Prasad presumed that her photo could be placed on Japan. The teacher was uneasy about this. Eventually Prasad was returned to her class, the photograph in her possession, not added to the mosaic map of multiculturalism for her school. She knew her story was “too complicated” and assumed they found a “real” Japanese student to be placed on the map.

The funniest of the collection is a piece called “The Half-Breed’s Guide to Answering the Question” by M.C. Shumaker who describes herself as half Cherokee. The question is, of course “what are you?” and her responses range from “The Obvious” (I’m human) to “The Hulk” (where Shumaker is sarcastic, rude and loud) to “Nothing But the Truth.” The last choice takes longer to do, but is worth it in the way it can dispel racist myths.

All in all a wonderful collection, with a large selection of very diverse experiences. Highly recommended.

May Lui is a Toronto-based writer, blogger and occasional contributor to rabble.ca. Her Chinese father and her Romanian/Polish Jewish mother met in Montreal in the 1960s. Don’t ask her the “what are you?” question.