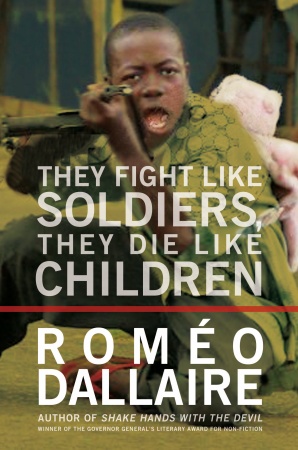

As Monia Mazigh pleaded for the conviction of Omar Khadr to be taken seriously by those concerned with the use of child soldiers, I was reading Romeo Dallaire’s latest book, They Fight Like Soldiers, They Die Like Children.

In it, Dallaire, too, shames the Canadian government and public for not acknowledging the injustice enacted by neglecting Khadr, the first convicted child soldier since World War II. He asserts that “the Khadr case is a black mark on my own country’s international reputation and standing in the fight for child rights and human rights as a whole.” Today, Khadr’s situation remains grim.

Children as a weapons system

Throughout his book, Dallaire engages with the issue of child soldiers on a number of levels: first and foremost from a military perspective, as that is the bulk of his firsthand experience. But additionally he comes at it from political, humanitarian, even economic perspectives. And in three chapters powerfully written from the first person perspectives of fictional characters, he urges engagement with the issue on an emotional level, too. I appreciate this effort to humanize what otherwise can be discussed as merely a conceptual or political matter.

In these ways, he effectively conveys the complexity of the issue at hand. By considering the multiple global and local dynamics at play, he acknowledges that singular approaches are not likely to bring about the kind of systemic change required to eradicate the use of children as a weapons system (this is his preferred terminology for the barbaric phenomenon). His intention is not to paint such a dismal picture that readers are left to throw their hands in the air in exasperation. Rather, he illustrates through numerous examples how the multiple facets of this complex dynamic are inter-related.

So although I, as an individual, cannot necessarily bring about wholesale change in one fell swoop, by recognizing these intricate connections (among such seemingly disparate issues as poverty, small arms manufacturing, gender inequities and conflict over resources, for instance), perhaps small changes in one of these areas of concern might in fact provoke other changes that are, as of yet, unforeseen — if the connections are appreciated and an overall vision is sought. In this way, the complexity Dallaire highlights does not lead to hopelessness, but instead an urgent sense of responsibility that each of us must do what we can.

Returning to the issue of Khadr, I will acknowledge that as a Canadian citizen, I felt dismay at my country and personal defeat regarding my own potential to affect any kind of impact in relation to his situation. But this may be a product of my inadequate understanding the processes by which this former child soldier was left to the lions.

R2P defined

Dallaire has made it a personal project to deeply understand the plight of child soldiers beyond the headlines. In his book, he discusses the doctrine of Responsibility to Protect (R2P) which states:

“that no sovereign state or its authorities can deliberately abuse the human rights of its citizenry and claim that no other state has a right to interfere. It says that should such a scenario present itself, or in the case where a government cannot stop such massive abuses of innocent civilians, then the international community has a responsibility to protect those civilians under a mandate from the UN.”

Of course such a doctrine does not simplify matters in terms of what to do; within it are nested a great many important considerations, particularly in relation to power dynamics and the potential for a wave of (possibly well-meaning) colonizing practices. But these concerns aside, at least it opens up the dialogue around current abuses of power, such as the use of children as combatants in 75 per cent of the world’s conflicts, and the responsibility we all share towards our fellow citizens.

Despite being an R2P signatory, Canada has been less than a leader when it comes to formally acting upon that responsibility. For example, we continue to produce and export small arms and ammunition, which Dallaire and others argue directly contributes to the capacity of forces worldwide to use children as soldiers. We also continue to engage in situations in which we may have something strategically to gain (such as our current presence in Afghanistan), but not in those places where the only thing at stake are people (such as our current absence in the DRC).

Our apathy in Khadr’s case is thus (sadly) not out of the ordinary.

While unravelling the many political, strategic and cultural complexities of the continued use of child soldiers throughout his book, Dallaire does not allow the reader to blame governments and policies alone. He reminds us that we constitute those bodies and policies, and as citizens it is our responsibility to push our leaders to engage differently; “As we bore down to what each individual citizen can do, we have to figure out how to compel our politicians to act.”

The use of child soldiers poses a serious violation to human rights, sets the stage for long-term global instability, and leads to the creation of areas in which whole generations of children are socialized into war. Many countries that are now home to former child soldiers — including Canada — directly and indirectly benefit from their use; through the trade of small arms and light weapons, resource extraction and global markets, for example.

Putting our values into action

My sense of hopelessness when reading the headlines about Khadr’s conviction may have been due to my lack of imagination regarding the possibilities as to how I can engage with such matters as a citizen. Rather than seeing his case as a singular, horrific “excess,” I must recognize it as an indication of a very broken system. As Naomi Klein reminds us (drawing from Simone de Beauvoir) in The Shock Doctrine, “There are no ‘abuses’ or ‘excesses’ here, simply an all-pervasive system.” If the use of child soldiers is nested within a global context of inequity and special interests; if global trade, gender inequity, and political self-interest (among other things) are somehow at the root of this messy reality, then these cannot be the systems from which we draw when seeking a way out.

Indeed, although he works within the systems that currently exist, Dallaire also urges systemic change throughout his book. He goes so far as to call for a revolution by saying that “the intensity and magnitude of the revolution is already beyond a mere ‘shift.'” Importantly, even the smallest of actions — if enacted with foresight and a larger picture in mind — can serve as contributions to such a movement. But this will not happen if I allow my imagination to be limited by the headlines.

I agree with both Mazigh and Dallaire that we have thus far failed to put our values into action when it comes to the plight of Omar Khadr. And when I think about the fact that we can simultaneously get up in arms about the issue of child soldiers, but not about the plight of one particular child soldier, I worry that we have come to see the big picture without recognizing the many parts that comprise it. And perhaps these are where the seeds of possibility lie.—Janet Newbury

Janet Newbury is currently a PhD candidate, instructor, and researcher at the University of Victoria. She is also involved in a number of social justice-related initiatives in her hometown of Powell River, British Columbia.