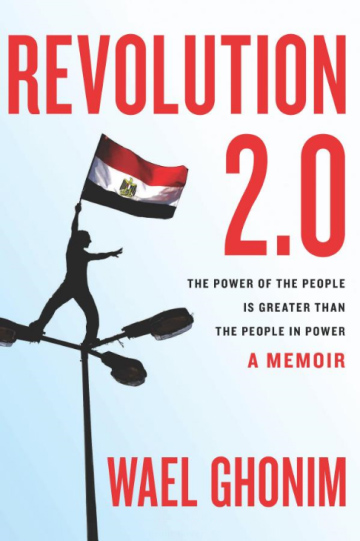

Reading Revolution 2.0 against the backdrop of the current unrest in Egypt, one can’t help but feel nostalgic.

After all, this book is an ode to the belief that people have the power to choose their political, social, and economic destinies — at least if they unite in their struggle for justice.

And for all of us, it indeed seemed possible as we watched the Egyptian revolution unfold, when citizens who had up until been “unengaged,” “cautious” and “intimidated” finally broke through the barrier of fear. Who can forget those staggering scenes in Cairo’s Tahrir square full of millions of hopeful, demanding, persistent demonstrators finally finding their voice?

Wael Ghonim is the unassuming and accidental facilitator who helped give voice to oppressed, angry, demoralized youth on Facebook. The success of the revolution speaks to unimaginable reach of social media in uniting citizens like nothing else before in history.

“…Thanks to modern technology, participatory democracy is becoming a reality,” he writes in the book, a memoir he rushed to get into print before the first anniversary of the revolution in 2012.

“Governments are finding it harder and harder to keep their people isolated from one another, to censor information, and to hide corruption and issue propaganda that goes unchallenged. Slowly but surely, the weapons of mass oppression are becoming extinct,” he writes.

And even though it feels as though rose-tinted glasses are badly damaged in the ongoing power struggles in Egypt and Tunisia, these realities cannot nor should they negate the immense leaps that citizens in these countries have made in regaining their agency. It would due them injustice to forget how mobilization on such mundane social platforms led them to come out onto the streets and agitate for rights long withheld.

Few Egyptians ever thought they would see the backside of a regime that had terrorized and robbed the nation.

“Today they killed Khaled. If I don’t act for his sake, tomorrow they will kill me.”

That was the first Facebook posting that Ghonim published on a newly created page dedicated to the memory of Khaled Said. Said was a young student in Alexandria, seated in an internet café when two police officers attacked him, took him outside and beat him to death. Some reports said he was downloading images of police brutality himself when he was caught, others say he infuriated the officers when he refused to acquiesce to their request that everyone leave the café so they could have it to themselves. Regardless of what truly transpired (the government claimed he was a drug dealer), the photograph of his bloodied, swollen and disfigured face served as a lightning rod for Ghonim who galvanized thousands to stand up against a regime that had routinely tortured and terrorized its populace.

As a tech-savvy graduate, with an MBA to boot, Ghonim knew that Said’s gruesome image — especially when aligned next to the photo of his clean-cut and handsome face from before the attack represented all that was wrong with their government. But Egyptians were still afraid of the regime and Ghonim knew he would have to engage people with the underlying injustice without directly criticizing or insulting the government which up until then would still alienate most of mainstream society. The population had been fed on a steady diet of propaganda for decades and was not accustomed to seeing and hearing about events that were relegated to furtive conversations.

“The media’s suppression of the physical world made the virtual world a critical alternative for promoting the cause,” he writes.

He started the Facebook page ”Kullena Khaled Said” — “We are all Khaled Said” which slowly grew into the avalanche of social engagement that would see the page go from 49 views to over close to half a million in a matter of months, culminating into the mobilization of hundreds of thousands of people just over a year later, on Jan. 25, 2011 marking the start of the revolution.

But before all that, Ghonim had landed a dream job with Google, working from Dubai. His commitment to the cause continued and he administered the page and call for revolution anonymously. The Facebook activism led to coordination of “Silent Stands” against police brutality, and eventually, inspired by the events in Tunisia, calling for the ouster of President Hosni Mubarak and his band of corrupt officials.

The book includes dozens of the actual Facebook postings which help weave a detailed and step by step account of how the seeds of revolution were planted, nurtured and eventually sown. But even more importantly, it serves as a guide as to how consultation and openness to people across social and class lines can lead the way to a united front against a despotic and corrupt regime.

Ghonim admits he isn’t the hero of this story. The story of the Arab spring is indeed one that reflects the heroics of collective groups of people — some of whom sacrificed their lives and limbs. At one point, a police officer was shooting directly into the eyes of protesters in Tahrir, blinding many.

But there is little doubt that Ghonim, who was imprisoned on the eve of the culminating protests in Tahrir, and remained oblivious to the struggles taking place on the streets from Jan. 25 until just before President Mubarak abdicated, was a hero. He’s the kind of hero that probably lies dormant within all of us — the one made stronger when united with other brave souls. Sometimes, all that’s needed is the right platform.—Amira Elghawaby

Amira Elghawaby is a contributing editor at rabble.ca.