The Penthouse Nightclub, the kind of place the tabloid press usually describes as “notorious,” was known to be a centre of prostitution in Vancouver when, in the summer of 1975, the police launched an operation to shut it down. After a lengthy investigation involving wiretaps, hidden cameras and undercover surveillance, the vice squad came calling just before Christmas and arrested the three Philliponi brothers, who ran the club, along with three other employees.

The doors were padlocked, the business licence was revoked and the city’s most infamous night spot — the Vancouver Sun columnist Allan Fotheringham once called it “a minor league equivalent of the Eiffel Tower” — went dark. Nine months later the trial of the “Penthouse Six” began.

The Crown charged that the club was a hotbed of sex and depravity, and the Philliponis (or Filippones; to confuse matters the brothers spelled their name differently) were nothing but pimps and procurers. The trial was labelled the “Charge-sex trial” after the Chargex credit cards that were used by patrons to buy sexual services.

The court heard lurid testimony from underage girls who claimed they had gone to the club to turn tricks; from a prostitute who appeared on the stand in wig and sunglasses for fear of being beaten by her pimp; from another 17-year-old prostitute, who testified that before she could use the club as a rendezvous she had to perform oral sex on one of the brothers (this testimony was later refuted when she proved unacquainted with the penis in question).

Meanwhile, one of the undercover detectives admitted to getting drunk at the club and dating one of the dancers. All of this splashed across the front pages of the newspapers day after day, keeping the city titillated for weeks. There hadn’t been so much excitement since the decrepit film star Errol Flynn died in the arms of his teenage inamorata in a West End apartment 17 years earlier.

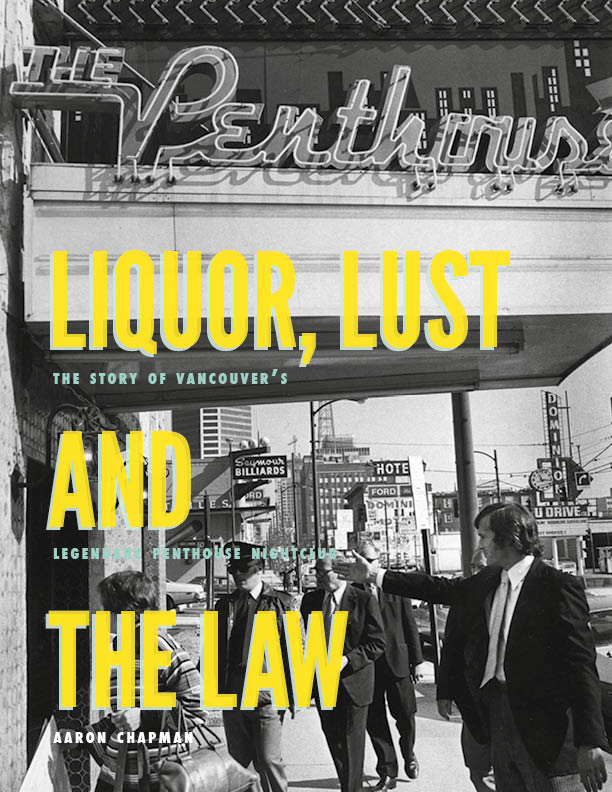

In one sense the Penthouse affair, which is detailed in Aaron Chapman’s lively new book, Liquor, Lust, and the Law: The Story of Vancouver’s Legendary Penthouse Nightclub, reads like a comical episode from a Damon Runyon story. Certainly the lead actor, Joe Philliponi, feels like a character out of The Sopranos, with his flamboyant personality and eccentric fashion sense — one reporter wrote that his wardrobe “looks as if it was pulled at random out of a spin dryer.”

Testimony at the trial showed a widespread use of the club as a place where sex workers met their clients. The Philliponis could hardly deny this was the case, but they argued that they could not be held responsible for everyone who visited the club. Their lawyer pointed out, accurately, that no tricks were turned on the premises and management took no share of the women’s proceeds.

“It was just a question of boy meets girl,” Joe Philliponi told the judge, portraying the strip joint as an innocent lonely hearts club. But the judge was unconvinced. He convicted five of the accused of conspiring to live off the avails of prostitution and sentenced Joe and one of his brothers to jail.

Ultimately an appeal court overturned the convictions and the Penthouse got its business licence back. But the air had gone out of the balloon. Attendance at the club fell off and the Penthouse, perhaps because of the publicity surrounding the trial, began to seem more vulgar than glamorous.

It was said that the Philliponis were linked to the mob, a rumour that gained strength in 1983, when Joe was murdered in his home next door to the club during an amateurish robbery. Then, improbably, burlesque made a comeback and so did the Penthouse.

Today the club is thriving under the management of Danny Filippone, son of one of the brothers. It was Filippone the younger who discovered the hidden cache of old photographs that makes Liquor, Lust, and the Law such wonderful browsing. Harry Belafonte, the Mills Brothers, Sammy Davis Jr., Joe Louis, Billie Holiday, Victor Borge, Les Brown and his Band of Renown, Louis Armstrong — their photographs all adorn the pages of the book, as they do the walls of the club, along with my personal favourite, the four Ladybirds, “the world’s first all-girl topless band.”

But the Penthouse trial was much more than a nostalgic episode from Vancouver’s golden age of nightclubs. It had important implications that reverberate in the city today. By closing the club and others like it, police flushed several hundred working women into the streets to find their customers.

Chapman quotes a retired police officer: “As far as I was concerned, the Penthouse was never a problem. I knew what was going on. But it was controlled there. After the trial, the hookers poured out into the streets all over the city, and it became like trying to capture quicksilver to manage it again.”

The decade that followed was marked by an intense debate about prostitution in the city as the on-street sex trade flourished first in the central downtown and then in the West End. Finally residents rebelled and, with violence threatening, the city obtained a court injunction to clear the prostitutes out of the west side.

But this was no solution. Prostitutes simply shifted their activities from one neighbourhood to another. Ultimately they were forced into the darkest corners of the city’s downtown, where they were easy victims for sexual predators.

By coincidence, at almost the same time as Chapman’s book appeared, so did the final report of Wally Oppal’s months-long inquiry into the police investigation of the Robert Pickton case. As I hope no one needs reminding, Pickton is the predator convicted in 2007 of the second-degree murder of six women at his Coquitlam pig farm and accused of killing at least 20 more. (The Crown decided not to proceed with prosecution on these latter charges, having already sent Pickton away for life.)

In a nutshell, Oppal’s report, titled Forsaken: The Report of the Missing Women Commission of Inquiry, concluded that the police — both city police and the RCMP — had botched the job of hunting down Pickton. “The missing and murdered women were forsaken by society at large and then again by the police,” Oppal wrote.

With the benefit of hindsight, many people have drawn a direct connection between the Penthouse raid in 1975 and the series of murders and disappearances leading to the arrest and conviction of Robert Pickton many years later.

In his book Aaron Chapman seems to agree, quoting one of the club regulars: “The girls were safe there, and under cover. Big deal if the Filippones grabbed an end, but why shouldn’t they? They paid the taxes and kept the place safe. If some weirdo like Pickton would have come in, [they] would have remembered him and known what cab number he and the girl left in. They kept an eye out for people.”

In other words, it was the police and the laws they were asked to enforce that pushed the missing women into the arms of a serial killer.

The Penthouse raid was not the only enabling factor in Pickton’s string of murders. Public hysteria and hypocrisy about street prostitution; the failure of civic officials to contemplate ways of keeping the women safe, not just out of sight; federal laws that encourage unsafe practices among sex workers — all these things allowed a predator like Pickton to do what he did for so long.

Still, the link to the Penthouse raid cannot be denied. Before 1975, no sex workers were known to have been murdered in Vancouver. Then, inexorably, the number began to climb until finally in the 1990s the press and the public realized there were dozens of unsolved murders and disappearances among the city’s street prostitutes.

This is the real significance of the Penthouse Nightclub to the story of the city: that it was the place, in the mid-1970s, where the seeds were planted for the worst episode of violence against women in Canadian history.

Daniel Francis is a member of the editorial board for Geist Magazine and writes a regular column there on books. He is author of several books on Canadian history and has contributed reviews and articles to numerous Canadian periodicals. He can be found on his blog Reading the National Narrative.

The review originally appeared in Geist Magazine and is reprinted with permission.