Please support our coverage of democratic movements and become a monthly supporter of rabble.ca.

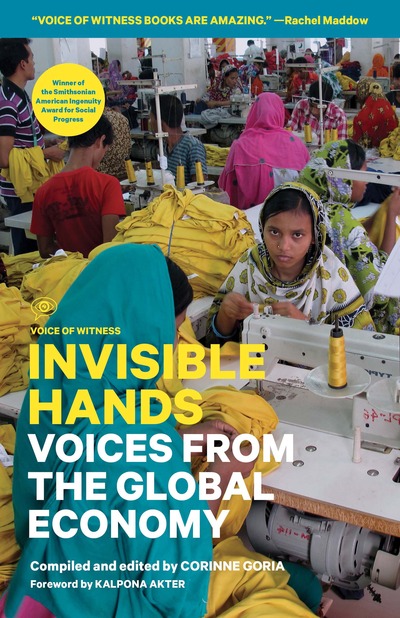

The stories in Corinne Goria’s Invisible Hands paint a horrifying portrait of the impact of rampant consumerism on communities and individuals from Bangladesh to Zambia. But while the workers experience profound disrespect, they dream of equity, fairness and workplace decency.

Several decades ago, after dropping out of school, a friend of mine found work as a hospital porter. While pushing his broom and mop, he often overheard the health centre’s administrators discussing high-level internal policies, information that he then turned over to his union. When the union later used this data in its organizing campaigns, the bosses were flummoxed, totally unaware that they, themselves, had transmitted the material. As far as they were concerned, speaking in front of a lowly porter was akin to speaking in a private setting. In their eyes, he was invisible.

Similarly, we rarely consider the day-to-day lives of the women and men who harvest our food, sew our clothes, assemble our electronics or excavate gold and other minerals. Of course, we know that countless people work in these occupations, but for the most part we don’t spend a lot of time thinking about the dangers they face or the exploitation they experience.

The 16 oral histories in Corinne Goria’s excellent anthology Invisible Hands is an attempt to change this by elucidating the realities behind the scenes of the so-called global economy. While each of the book’s four chapters is preceded by a brief overview of working conditions in a particular occupation, individual accounts form the bulk of the text. And although these accounts are not wholly eye-opening — numerous labour journalists have covered worker mistreatment consistently in articles and books — when taken as a whole they illustrate the profound disrespect that greets far too much of the world’s workforce. What’s more, the stories in Invisible Hands paint a horrifying portrait of the impact of rampant consumerism on communities and individuals from Bangladesh to Zambia.

One of the most dramatic accounts comes from Kalpona Akter, a Bangladeshi seamstress turned labor organizer, whose employment in an exploitative garment factory began when she was 12. Among the indignities she experienced was the boss’ refusal to pay bonuses for overtime, even after workers had spent 16 straight days hovering over their sewing machines to meet a deadline.

Akter was 17 when she went on strike for the first time. Already married, her husband bristled at her involvement and assaulted her for participating. Nonetheless, when she heard that classes in labour law were being offered by the Bangladesh Independent Garment Workers Federation, she wrangled her way into them. Shortly thereafter, she took it upon herself to share what she had learned with her coworkers,

“My husband was an anti-union guy,” Akter told Goria. “I was beaten by him because of my involvement with the union. … Also, when I tried to give some of my wages to my family, he beat me because he wanted me to give all my money to him.”

But Akter prevailed. She eventually left her spouse and got more involved in workplace organizing, something that had an immediate — and unanticipated — impact on her ability to support herself. Thanks to an industry blacklist, a host of activists, including Akter, suddenly found it impossible to work. Although she eventually was hired by a series of pro-worker community groups, troubles continued to brew. Indeed, the government of Bangladesh made clear that it would do whatever it could to suppress revolt and keep wages low. Worse, as workplace organizing ramped up, several of Akter’s colleagues were kidnapped, and she herself was arrested in 2010. “There was no cell for females,” she recounts, “so I had to sit on the floor in a tiny, dirty, office room. They forced me to sit squeezed behind a desk and a wall. The 2-by-4-foot space was so small I couldn’t even lie down. That’s where they kept me sitting, cramped, for seven days. I couldn’t sleep the whole time.”

After 30 days, Akter was released on bail, but backlash against Bangladesh’s movement for worker sovereignty continued to accelerate. Indeed, two years later, in April 2012, the tortured body of another organizer, Aminul Islam, was discovered 60 miles from their union headquarters. Sadly, Islam was not the only trade unionist to meet this fate.

Despite these grim events, Akter has not been deterred. In fact, she continues to be outspoken on behalf of Bangladesh’s garment workers, supporting the many campaigns that have come to fruition since the June 2013 Rana Plaza factory collapse that killed 1,100 and injured 2,500 workers.

Meanwhile, as demand for cheap jeans and T-shirts continues unabated, China has become the leading producer of the clothes hanging in our closets. Most of the cotton for this clothing, Goria writes, comes from India, the United States and Uzbekistan, and those who produce it often fare badly. In India, for example, Invisible Hands reports that more than 250,000 farmers have committed suicide since 1998 — the largest wave of suicides in human history. “A great number of those affected are cash crop farmers, and cotton farmers in particular,” the book explains. “In 2009, 17,638 Indian farmers committed suicide — that’s one farmer every 30 minutes.” The reason? According to Goria, numerous surveys and reports link farmer suicide to debt and the pressure to repay high-interest loans. “Increasingly,” she writes,” farmers borrow money to buy seeds, fertilizers and pesticides. The cost of these investments has risen dramatically, even as the market has kept the price at which farmers can sell their cotton relatively flat.”

Closer to home, Neftali Cuello, now 17, tells her interviewer about working in a North Carolina tobacco field. Because farm work is not bound by the same age restrictions as other employment, Cuello spent four summers working 64 hours a week in extreme heat and humidity. She told interviewers that after her parents separated, she and her mom and siblings moved to Pink Hill, North Carolina, where her mom found work, first on a pig farm and later as a tobacco picker. By the time Cuello was 12, she understood that family finances were extremely tight. And as soon as school let out, she began working as a “sucker,” removing the tobacco shoots that grow between the leaves of the plant.

She recalls the first day as pure hell. “Within two or three hours I was feeling nauseous,” she begins. “It was because of the nicotine. The leaves were really sticky that day. I think the plants had been sprayed with pesticides like maybe a couple of hours before, or the day before. You could really smell it.”

Cuello further notes that heat stroke is a common occurrence, and she and her coworkers were never told how to avoid becoming ill. Likewise, they were told nothing about nicotine poisoning and were given no protective gear or advice on precautionary behavior.

Safety is also a huge concern for workers in aluminum, borax, copper, diamond, gold and uranium mines, as well as for those working in energy production. In addition, the people who produce the electronic gadgets we rely on often risk life and limb to keep us connected. Twenty-six-year-old Li Wen, for one, lost a hand while cutting machine parts at an electronics plant in China. Although he sued the company for violating safety protocols, he won only a small settlement — about $19,500 — and is presently at a loss about what to do with the rest of his life. “I have to come up with a plan of some kind,” he says. “I hope to have my own family. I’d like to get married but that might be difficult. I’d like to find a nice girl but she’ll need to accept my disability. … I’m thinking of starting my own business but I don’t know what kind of business I would do. I don’t feel very confident and I don’t have any experience. I don’t have a clear plan about how I should work it out.”

All told, the accounts in Invisible Hands are horrendous, yet to a one, those interviewed are optimistic that employers can be forced to respect those who toil in occupations that are largely unseen by consumers. They envision workplaces in which hard work is valued and adequately compensated, demands that are neither radical nor unattainable. Still, all agree that victory will not happen without coordinated, collective action. Furthermore, they concede that there is no roadmap to successful organizing. That said, the interviewees believe that by sharing their narratives, they are helping to kick-start a movement in support of equity, fairness and workplace decency. As Akter writes in the book’s foreword, “We share our stories in this collection to engender outrage, but also to cultivate an imagination of what is possible. It is through stories that we come to care, come to believe, and are ultimately transformed until we can no longer be silent.”

Let the shouting begin.

Eleanor J. Bader is a teacher and freelance journalist based in Brooklyn, New York, She writes for RHRealityCheck.org, The Brooklyn Rail, Theasy.com and other progressive and feminist blogs and magazines.

Copyright, Truthout.org. Reprinted with permission.