A bold vision for Canada’s future: what would that look like to you?

Would it encompass a new outlook on justice and politics, or would it emphasize equality and equity or would it require a look back on Canada’s past in order to better see the future? Would it be all of these things?

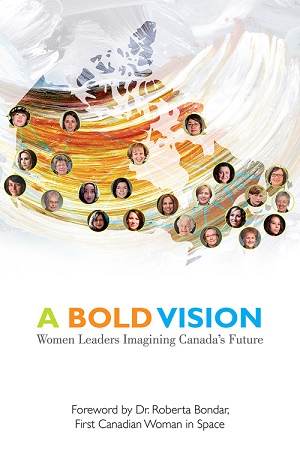

When the members of A Bold Vision Steering Committee posed this question to numerous women leaders in Canada, A Bold Vision: Women Leaders Imagining Canada’s Future was born.

The anthology’s list of contributors reads like one conjured from the question “If you could have dinner with any Canadian feminist hero, who would it be?”

From Niki Ashton to Pamela Palmater to Bonnie Brayton to Lana Payne to Shelagh Day to Kluane Adamek to Eva Aariak, each contributor’s essay is astounding, thought-provoking and necessary.

Fairness, equality, history and possibility; environment, feminism, politics and justice: the diversity and breadth of issues covered in this collection is a testament to the ultimate vision that is formed upon reading A Bold Vision.

In the excerpt, Jessie Housty, an Indigenous community leader from the Heiltsuk First Nation in Bella Bella, British Columbia, focuses on social and environmental justice through reconciliation and radical storytelling.

What is Jessie’s vision for Canada’s future? Read below to find out!

Reconciliation and Radical Storytelling: A Vision for Transformation in Canada

Beginnings

The First-Generation stories of the Indigenous peoples across Canada have many common narrative threads. Among them, we consistently see the figures of “Creator,” “mother,” and “trickster.” Givers of life force. Women who give birth to Nations. Wise and wily figures whose magic brings us light and knowledge. While remaining clear that this continent has hundreds of distinct peoples, it is still arguably simpler for us to find those common narrative threads among ourselves than to find them in the predominant colonial culture whose “First-Generation” stories instead privilege and are constructed around archetypal characters who are conquerors and heroes. The figures central to the plot of Canada’s colonial narratives are portrayed as righteous and mighty. From the very first, they are “discoverers” and “civilizers” — roles that imply an absence or deficiency of stories extant in this geography at the time of European contact.

One story meets another. One storyteller meets another. And from the time of contact to the modern day, we see a natural but destructive impulse at play: Indigenous and Settler people have simply been characters and plot devices in one another’s stories. We have catalogued one another in our systems of knowledge and narrative. But we have not yet learned the act of telling stories together.

The Starkness and Silence of Winter

As an Indigenous woman in Canada who lives in service of her people and her communities, I know at the root of my heart that the issues we face are abundant and real. They are embedded in the legal, institutional, and policy framework of this country. They relate to the social and economic situations of Indigenous peoples; the space for Indigenous peoples to participate in society; the integrity of treaty and other claims processes. They are tied to health, education, justice, stewardship, and self-government. They are issues of principal human rights.

At one time, this continent was criss-crossed by the traplines and moccasin trails of many sovereign peoples. They had their own languages and governments, their own relationships to place and one another, and a scale of time that measured progress and change in generations — in millennia. From the time of contact, that timescale has rapidly shifted. Physical violence — whether in the form of warfare or waves of disease — caused deaths in such staggering numbers that the ceremonies of burial and mourning could no longer be adequately practised by those left behind. Since then, the narratives and policies of erasure in this country have subjugated the stories and histories of the Indigenous people whose collective knowledge, passed generation to generation, itself represents the fullest and longest story to come from this land.

One of my elders has teaching tools she has developed to help Settlers working in our territory to understand the values, stories, and history of my people — the Heiltsuk people, whose territory stretches through that threshold space where the mainland of central British Columbia scatters into islands that seed the Pacific’s edge. One of her tools is an image. It represents the continuum of Heiltsuk history to the present day, and it marks known incidents of great importance: Creation, the founding of the first villages, the Great Flood. There is also a marker that denotes European contact; it is situated so close to the end of that long continuum that it seems a tiny speck.

This is the Heiltsuk worldview. We have tens of thousands of years of history as a people, and only a couple of recent centuries are shared with Settler peoples. In the stories our elders pass down to us, there was a point in pre-contact history when our Heiltsuk people were as numerous as the trees. Certainly, there were tens of thousands of us stretched across the span of our territory. After contact, and after waves of disease that nearly exterminated us, there were fewer than 200. But we are still here.

Today, Indigenous people make up a little over four per cent of Canada’s population, and we are the fastest-growing segment. The demographics are dry but informative: There are 617 bands, around 50 cultural groups, and around 1,000 centralized Indigenous communities in this country (with many Indigenous individuals also residing in cities and towns where they represent a minority). But beyond the demographics, what is perhaps more compelling and powerful is the fact of the social and cultural fabric of our lives within Canadian society.

If this is uncomfortable to read, be patient, and make space for it: This country has seen episodes and alarming patterns of unjust and devastating human rights violations against Indigenous peoples from the time of Settler contact. The Indian Act, a statute originating in the 19th century, is still used as a tool in attempts to control many aspects of our governance and identity, and with only minimal reforms since its first articulation. My parents’ generation still remembers the Potlatch Ban, a period stretching into recent history when expressions of culture and ceremony were made illegal.

My grandparents’ generation still remembers the Indian Agents who controlled whether our people were allowed to leave the reserve. Policies were enacted that stripped people of their Indigenous identity and membership before they were permitted to participate in institutions such as the military or the academy. A history of Settler-Indigenous relations recounts exclusions of our people from voting or jury duty, blocked access to lawyers and legal remedies for land-related grievances, and the imposition of colonial governance structures intended to supersede our own millennia-old institutions of governance. Some of these practices are ended, yes. But together, the patterns and episodes add up to an attempt at erasure, and this is a reality we must confront If you’re about to tell me “It’s in the past,” if you’re about to say “Let it go, move on,” you’re not the first. But what you need to know is that I am the sum of all the stories that brought my people, my great-grandmother, my grandmother, my mother, to the point at which I entered the world. My stories, whether collective or individual, are my identity. And many of those stories are more current than you might think. If you’re uncomfortable right now, ask yourself why it’s so important that this narrative of racism and oppression be rooted in the distant past. Don’t worry — this conversation is a safe space.

It’s easy to insist that these narratives have ended, because then we don’t have to confront the fact that the effect of those narratives is still felt today — and that many of them are, in fact, still unfolding.

There is a dark century in that history of Settler-Indigenous relations. The residential school era. Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their homes, families, and communities with the explicit intent of “killing the Indian in the child.” Hear the story: These children were whipped for speaking their mother tongue. Hear the story: These children were stripped of their names. Hear the story: These children felt their bonds with family and community and culture deliberately and systematically beaten out of them. I don’t need to hyperbolize. The survivors have been generous with their painful stories.

We all need to hear them and make space for that pain. Thousands of Indigenous children did not withstand this assault on their bodies and their identity. Many are buried in unidentified graves. Those who did survive bore the ugly scars of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse. They grew up estranged from their people, their language, their culture, and their identity. During the “sixties scoop,” Indigenous youth were again removed and fostered out into non-Indigenous homes in Canada and abroad, prolonging the legacy of broken bonds and lost children. You might push this legacy away, say it’s a distant past that just has a long shadow. But hear the story: I am twenty-seven years old, and in my family, I am part of the very first generation in which no child was forcibly removed. For some people, these are historical and academic issues. For me, they are the context in which I’ve grown up, the story I’ve inherited to carry on behalf of those who came before me. I’m not describing the darkness to instill a sense of guilt. I’m giving you a window into my lived reality. I’m showing you the darkness in the hope that we can illuminate it, together. Not erase it, but open up a crack through which a beam of light might enter. This is a trailhead on the path to reconciliation. For me, these issues are a narrative not just of Indigenous peoples — but a narrative of Canada — and in my work, it is imperative that we agree to speak the truth, to know that the truth must be spoken. If we are going to undertake work here together, we must begin by acknowledging a set of facts that is not simply academic, but vital, visceral, and still intimately tied to the policies and frameworks that guide Settler-Indigenous relations in this country today. Yes, hear the story: today.

The Song Inside the Bird Inside the Egg

There is a custom amongst my people that carries great meaning for me. It goes like this: Stories are ceremony, and ceremony is power, and power can heal. When there is a wound, whether it is physical or spiritual or any other kind, the path to healing is in the cleansing act of storytelling. Our “washing ceremonies” ritualize storytelling to create a process for grieving, for loss, for pain, and then for healing. But the healing is not possible without first establishing truth — without first telling the story. Storytelling makes grieving and healing a responsibility that is shared with everyone who hears the story. The process requires trust. It requires that we all be tender and brave, and above all, gentle with one another. It requires that we honour one another and make space for what is so generously given, even (and especially) if the thing that is shared is pain. It breaks down the false dichotomy that separates “storyteller” from “audience.” Once the story is told, everyone who hears it has a responsibility to help carry it. This is the space where healing is made possible. Storytelling is both the most powerful and the most radical act we can commit. Ask yourself what stories and histories and narratives in this country have been subjugated through time, are being subjugated now. Then ask yourself why. Acknowledge that it is time for us to come to a critical consciousness. It is time for us to be unafraid of stories. The interruption of healing narratives is a threat to our wellness. It’s a threat to our wholeness. We must tell stories readily. To be radical in our healing power, to be radical in our intervention, we need to tell the stories and impart to those who listen their new responsibility to help bear the pain and the healing and the power of the telling. If you’re asking yourself which stories are the important ones, it’s all of them. Every story we share. Every story that is part of our identity. And sharing them is a ritual that uplifts us as storytellers. It is a ritual that uplifts the cultures, the places, and the junctures where stories are born. It is the most radical and, frankly, the only act we can still undertake that yet has power. To listen, and to speak. To our ancestors, to ourselves, to each other, to our children. To the children still to come.

The physical space of Canada as a country is already defined. But the geography of Canada’s stories is not fully mapped, and the maps will never be static. Because stories are ways of being, of knowing, and of relating. They converge, and the points of convergence are powerful. They diverge, and the points of divergence are powerful. We must learn to tell stories without the impulse to erase or supersede the stories that came before. We must learn to tell stories without the impulse to possess the stories of others. In the Canada I envision, there are no olive branches; rather, there are people who say to one another, “Let me tell you a story,” and trust in their own truth, trust that their stories will be honoured and reciprocated.

The predominant archetypes in Settler and Indigenous storytelling traditions may differ, but there is an element in common: a magical story-space in which transformation is possible. Transitions I envision a Canada in which stories are sacred. I envision a Canada in which storytellers have the courage for their stories — and for their act of storytelling– to be radical. To be radical for as long as is necessary, until, as a culture, we recognize that stories are all that we are. The institutions of this country are not ready to make social change. They are not even designed or permitted to make social change. It will come from the people, and it will come from the community we create around the stories we share with one another. The telling of stories is the practice of freedom. The telling of stories is the practice of truth. The telling of stories is not a practice that is emergent. It is resurgent. And until the change is made, it is insurgent. Tell stories anyway.

It is time to be unafraid.

What is boldness? It is conviction. It is commitment. As a young Indigenous woman and leader, I commit to two things: To knowing the stories of my people, and to carrying them with me in anticipation of the day my daughters are born. Some of those stories are cultural, and they trickle back through time to the First Generation, to the moment of Creation. Others of those stories are more recent, and narrate the violence and oppression that is a part of my identity and the legacy I’ve inherited. The collective stories I hand down to my daughters will be unified by a narrative thread of hope; that is my intention, and that is my gift to them. I commit to holding those stories, and to sharing them, to knowing their truth. And I commit to being hopeful in my storytelling.

To my Indigenous sisters and brothers, I have this to say: Know your stories, and hold them, and share them, because through the generations of violence and oppression we are still here. We are resilient. We have stories that belong to us, and to which we, in turn, belong.

To my Settler sisters and brothers: Sit with the truth, even when it hurts.

Sit with the truth, even when you want to harden a shell, to protest, to defend yourself. Sit with the truth of the possibility that you benefit from the subjugation of Indigenous peoples and their stories. Commit to being solidary.

Commit to participating in change.

To everyone, regardless of the origin of your stories: Consider this an invitation to build a story-house with me. My stories are mine; you can learn them, but they are my identity. Your stories are yours; I can learn them, but they are your identity. There is a common space we can occupy together, though.

There is a story of Settler-Indigenous relations in Canada that is young; it is just beginning to unfold. Be a voice in the telling of that story. And in that singular, radical act, commit to the truth and the power of stories, and know that stories are all that we are.

Stories narrate our past. They shape our present. And the telling of stories is a fundamental act in determining our future. If there is conflict to come, let it begin with truth. If there is healing to come, let it begin with truth. Stories represent a dynamic space in which hope and transformation are possible. If the telling of truth is radical, so be it. If the telling of stories is radical, so be it.

The act of the telling and the possibility of the telling create a space in which we can boldly envision a country beyond Settler-Indigenous relations — a country in which a shared narrative is possible. Not a shared story rooted in erasure, but one that begins with radical acceptance — with a moment of convergence.

Jessie Housty is an Indigenous community leader from the Heiltsuk First Nation in Bella Bella, British Columbia. She received her BA in English from the University of Victoria and is currently pursuing her MA in English at the same institution.

Her work is based in the heart of the Great Bear Rainforest and focuses on capacity-building for social and environmental justice; land and marine stewardship; Indigenous governance; and leadership and collaboration. She is an elected member of Heiltsuk Tribal Council with portfolios related to stewardship and governance. She also works as the Communications Director for Qqs (Eyes) Projects Society, an Indigenous-driven non-profit with an open mandate related to Indigenous community development and intergenerational models for learning and leadership.

Her independent community organizing focuses on topics such as food security, energy issues, deforestation, sovereignty and self-determination, trophy hunting, and anti-oppression work.

She has worked as a teacher, facilitator, coach, and collaborator to help Indigenous and non-Indigenous individuals and organizations develop authentic, values-driven approaches to joint work. Her own work is rooted in the principle that sustained social change requires cultural shifts, meaningful collaboration, and a commitment to community-building.

Jessie Housty is a published poet, a contributor to numerous works of environmental literature, and a writer in The Tyee’s national pool. She was a finalist for the 2010 Ecotrust Indigenous Leadership Award, and an inaugural recipient of the University of Victoria Provost’s Advocacy and Activism Award in 2013. Jessie Housty’s motivation for change is rooted in both the past and the future — living by the principles and customs that are the legacy of her ancestors and honouring the generations to come by fighting to make this a world where they can flourish.

Jessie lives in Bella Bella, British Columbia, with five generations of family surrounding her.