Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

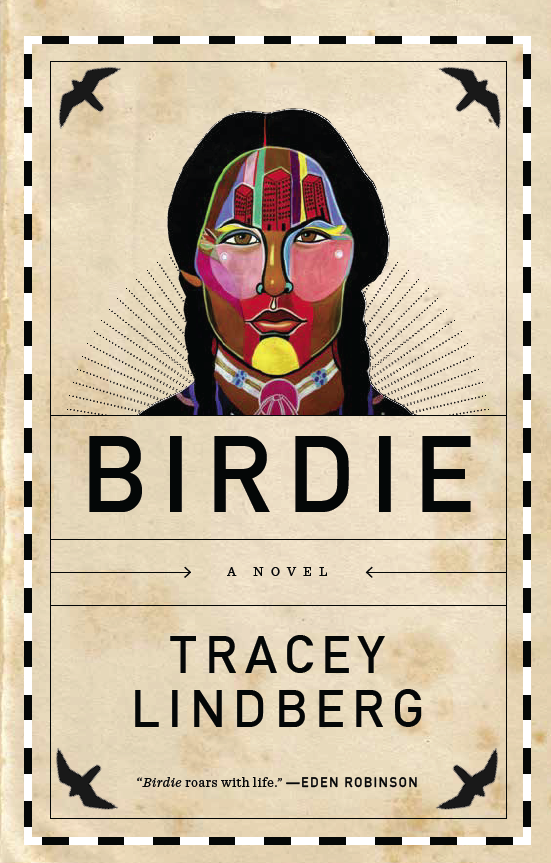

Tracey Lindberg’s debut novel Birdie is a celebration of Cree communities centered around the coming of age of a complex female protagonist.

Lindberg invites the reader to follow the quiet, iron-willed Bernice Meetoos on her journey from the Alberta reservation where she spends her early years to her Auntie Vals “Pecker Palace” to foster care to the streets of Edmonton and Gibsons, B.C.

Bernice is unmoored from the family and women who love her and plagued by a history of abuse, but her story is filled with warmth and humour as well as pain. It’s Slaughterhouse-Five by way of The Rez Sisters.

Clarissa Fortin spoke with the prominent Cree author and academic about Birdie, an “unstuck in time” narrative populated by vibrant Cree women. This interview has been edited and condensed.

In Birdie, one of the things I noticed right away was the language and the word combinations you were using like “bigelegance,” “sistercousin,” and “delighthorror.” Why did you do this? What does it mean?

Part of it is that on a very basic level I don’t think that English allows the possibility of a full discussion about relationships within many communities.

In this case speaking of a Cree community, the English language didn’t capture that there are shared, reciprocal relationships and obligations between, in this book, the women. So I started to put words together for what I knew to be true that there were and are people who have four or five mothers and who call grandparents mom and dad, that English doesn’t fully reflect the nature of our shared and dual relationships with each other in Cree communities.

Also in my family there’s a tradition of making up words to describe people and things and events. One of my aunties, my little mother, will describe people that she’s met during the day with a phrase that she turns. So it will be one word, all one word “bigmanonbuswhosnorts.” And then from then on he is known as that between my mother and my auntie every time they see that guy. “Oh I just saw bigmanwhosnortsonbus!”

How important was it for you to draw inspiration from the women in your life to write this book?

I have never met women like the women in my family on the page or on the screen and I have always thought that that beautiful relationship between my aunties and my mom and grandmother was really important to capture.

I’ve said publicly that… I wrote it as a love letter to my family and that’s true … [I] really wanted to be able to tell my mom and my aunties that we’re going to be okay. Whatever it is that we go through, whatever it is that Bernice [Meetoos, the main character] has gone through we survive, we thrive because of this love. This love is the thing that isn’t just for us to get through it, this is the thing that got us through it and it’s the thing that we have to recreate, the thing that we have to rebuild when we are impacted by all sorts of different things — in Bernice’s case a devastating history of sexual assault in the family.

And in my family’s case some of that but also … we’ve lost a language or we’ve lost ceremony. There’s a real hopeful note in it that I wanted my family and other women in the family to grasp hold of, that inevitably we’re going to have to build new things — but we can do that!

So, I wanted to reflect these beautifully unique relationships that I hadn’t seen anywhere else but also to let them know that those relationships are the building blocks to our “next” whatever our “next” is.

One of the things I had to check myself on as reading it was my tendency to diagnose Bernice. I saw her actions as the symptoms of a depressive breakdown — what do you think of this interpretation?

My response to it is the same as it has been all along that externally we call it that because we don’t understand it. We put a label on it because then we are more able to manage it, but at no time does Bernice ever say “I’m depressed.”

Nobody in the book says she’s depressed. Nobody talks about post-traumatic stress disorder.

I think that what I see her doing and what I hope that I created her to do was to not accept anybody’s label of what her health was but to be a self-determining person who made an assessment of what she needed and went and did it. She is clearly experiencing something from having been in that home and having been hunted for years and years and she’s managing it in the only way she knows how. But it doesn’t serve her in any way to self define in that regard so I don’t apply the label to her either.

But that’s why we read isn’t it? My intent or whatever I wanted to come of it is actually largely irrelevant when it’s in your home and you are in that intimate moment with the book. What it teaches you is between you and the book it doesn’t matter what I say.

This book is on the Canada Reads longlist. How did it feel to be put on that list? [Editor’s note: Congrats on making Canada Reads shortlist!]

I started crying. I don’t know how to express this adequately… I’ve surrounded myself by a great group of women who are doing fantastic stuff so i’ve been celebrating with them as they got nominated for this or that. And then when it happened to me I just had this overwhelming sense of “was there a mistake?”

There’s a part that just feels surreal. There is real male dominance in the marketplace for books. I heard Lee Maracle in an interview with The Current say that women are 80 per cent of the book buyers and yet 70 per cent of the books that are sold are written by men, and that we haven’t really used our buying power to give effect to that change.

I realized when I was so shocked that it was on the longlist that I was shocked because I had an expectation built on this very short experience that it would be men on the longlist. Which is a terrible thing to actually expect and makes it more of a surprise to me that it was more.

But I also thought oh in this short period of time I’ve become indoctrinated to believe that this is the train of men not women … we have to make some changes here. We have to have an open conversation about what we miss when we don’t talk about women or we don’t to women talking about women.

I wrote “Bernice Meetoos is unstuck in time” on a page of the book because the shifting timeline reminded me of Slaughterhouse Five. Why did you have this kind of non-linear narrative?

We have such distinctions in Cree communities in Kelly Lake. When we talk about time I hear people talking about places, like it’s not a timeline and it’s not linear. People talk about where things happened and in mapping it’s not the big English words it becomes the word that described what happened there.

So I like to think of the book’s framework or the book’s history, timeline, mapping as something that is event-based and that Bernice is unstuck in time — yes. Because time has no relevance.

What difference would it make if it was 50 years ago or yesterday to her? She hurts now and she feels ill now. So she starts looking to where that feeling came from. What was the incident the accident the activity the mapping point where you could say “this is where this came from.” So she talks about events. Where did she stay, where did she live, what happened. Where was she found …

I’ve had people talk to me about it who just couldn’t move beyond chronological sequencing. I know that it’s challenging but … I don’t mean to be so bold as to suggest I’m a part of this I’m just using it as a reference point, but if we’re going to be so married to the notion of reconciliation surely we have to look at the way that different peoples and different communities and different societies different nations tell their stories, tell their histories, map their locations, deal with time.

Your book has come out at a crucial time. Do you feel you’re adding a voice to a larger conversation happening in Canada right now about Indigenous narratives?

I think that that story would have been the same whenever it was written. The difference is Canada, the difference is not me.

[Birdie] actually was released the same week as the TRC recommendations were released — I have released a book at the same time when Canadians are examining their relationship with Indigenous peoples. It’s a coincidence and it has been beautiful because I’ve been a part of hard, difficult and lovely discussion. But I take no ownership of anything other than the luck of somebody who was already having this conversation.

Tracey Lindberg is a citizen of As’in’i’wa’chi Ni’yaw Nation Rocky Mountain Cree and hails from the Kelly Lake Cree Nation community. She is an award-winning academic writer and teaches Indigenous studies and Indigenous law at two universities in Canada. She sings the blues loudly, talks quietly and is next in a long line of argumentative Cree women. This is her first novel.

Clarissa Fortin is rabble’s books intern.