Carmen Maria Machado’s new memoir, In the Dream House, mirrors the way that trauma fragments our existence and depicts its afterlife in our bodies. Taking place during her two-year residency at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop, Machado tells the reader about an abusive queer relationship she had with an unnamed lover, who she refers to as the Woman in the Dream House.

The Dream House is the real home her lover resides in, ensconced in the woods of Bloomington, Indiana. It is also a literary trope. Each of the book’s four sections is divided into chapters labeled “Dream House as Time Travel,” “Dream House as Folktale Taxonomy,” “Dream House as Man vs. Self,” “Dream House as Choose Your Own Adventure.” Machado’s formally inventive structure is similar to her previous short-story collection, Her Body and Other Parties, which was the winner of the Lambda Literary Award for Lesbian Fiction in 2018.

Speaking to her past self in the second person, Machado writes: “You begin to experiment with fragmentation. Maybe ‘experiment’ is a generous word; you’re really just unable to focus enough to string together a proper plot.” She now understands her structural choices as the only option she had: “You say, ‘Telling stories in just one way misses the point of stories.’ You can’t bring yourself to say what you really think: I broke the stories down because I was breaking down and didn’t know what to do.”

In this move from first to second person, to a statement spoken (as indicated by the quotation marks) to one unspoken but now written, Machado’s change in narrative perspective reflects a phenomenon that those of us living with trauma know all too well: dissociation. The feeling that you are watching yourself from above, in a perpetual state of disconnection, is one of trauma’s telltale signs. In the Dream House offers readers a glimpse into effects of living with trauma in both form and content. We begin to see that this isn’t just a story about the trauma caused by abusive relationship between two queer women; it’s a story about the necessity and impossibility of writing about trauma.

Machado also begins to reveal how writing about trauma is both a literary and political problem.

In a chapter called “Dream House as Unreliable Narrator,” Machado recalls how, as a child, her parents would call her “melodramatic” and “a drama queen.” She’ll later explain this dynamic to her wife, therapist, and friends, noting how she was filled with “incandescent rage. ‘Why do we teach girls that their perspectives are inherently untrustworthy?’ I would yell.” Machado’s reflections prompt some questions: “How do people decide who is or is not an unreliable narrator? And after that decision has been made, what do we do with people who attempt to construct their own vision of justice?”

Machado will pick up this question in “Dream House as Proof,” ruminating on what counts as evidence:

So many cells in my body have died and regenerated since the days of the Dream House. My blood and taste buds and skin have long since re-created themselves. My fat still remembers, but just barely — within a few years, it will have turned itself over completely … But my nervous system remembers. The lenses of my eyes. My cerebral cortex, with its memory and language and consciousness. They will last forever, or at least as long as I do. They can still climb onto the witness stand. My memory has something to say about the way trauma has altered my body’s DNA, like an ancient virus.

As Machado personifies her body, I can’t help but imagine her nervous system climbing onto the stand and explaining to the court the ways in which trauma has refigured the body. For years, trauma specialists, including Gabor Mate and Bessel Van Der Kolk, and those working in somatic experiencing and polyvagal theory, have been writing about how the mind/body dualism is false. In the same ways that getting physically ill impacts our emotional and psychic well being, emotional and psychic harm, when unaddressed, can make our bodies sick. When Machado writes that “trauma has altered my body’s DNA, like an ancient virus,” she is not speaking in metaphor.

Unfortunately, these alterations to Machado’s DNA cannot testify on her behalf. Drawing on the work of the late José Esteban Muñoz, Machado understands that her trauma is a form of queer evidence. Quoting Muñoz’s Cruising Utopia, Machado writes: “The key to queering evidence…is by suturing it to the concept of ephemera. Think of ephemera as a trace, the remains, the things that are left, hanging in the air like a rumor.”

For Machado, the ephemera is “the recorded sound waves of her speech on one axis and a precise measurement of the flood of adrenaline and cortisol in my body on the other…The metal tang of fear in the back of my throat.” These traces are not seen; they’re felt in and through the body. “None of these things exist,” Machado notes. “You have no reason to believe me.”

While many people in Machado’s life speak of her story with incredulity, for those of us living with complex trauma and chronic illness it does not matter if “none of these things exist” as more than a trace, as ephemera. In attempting to write about trauma and its afterlife in our bodies, In the Dream House is an offering and an affirmation. In her dedication, Machado speaks to us: “If you need this book, it is for you.” And it is in the ephemeral traces that we find ourselves and one another.

Margeaux Feldman is a writer, educator, and community-builder from Toronto and now living in Treaty 7 Territory in Calgary. She’s currently completing her PhD in English Literature and Sexual Diversity Studies at the University of Toronto. Her writing has been published in PRISM, The Puritan, the Minola Review, GUTS magazine, and The Vault. She’s currently at work on a memoir entitled The Bed of Sickness: Essays on Care. You can learn more about her at margeauxfeldman.com

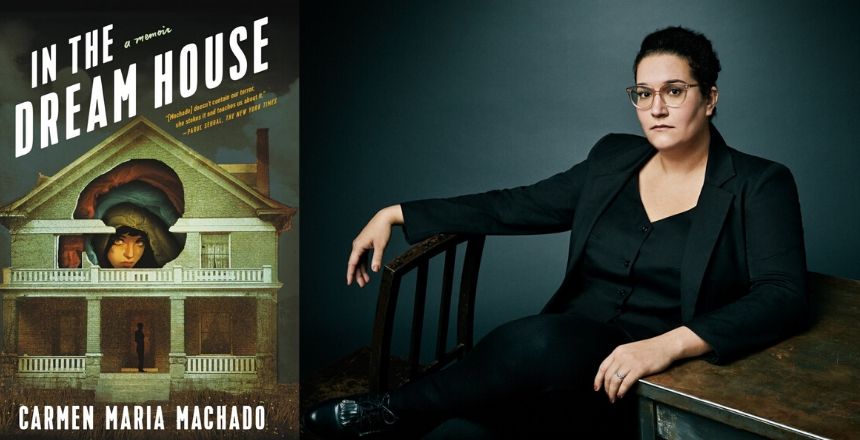

Author image: Art Streiber/August