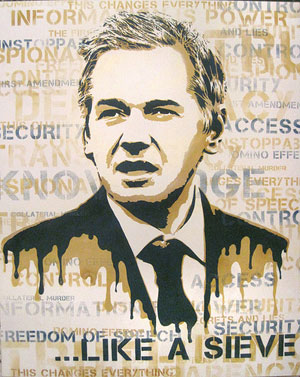

Last Saturday was sunny in London, and the crowds were flocking to Wimbledon and to the annual Henley Regatta. Julian Assange, the founder of the whistle-blower website Wikileaks.org, was making his way by train from house arrest in Norfolk, three hours away, to join me and Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek for a public conversation about Wikileaks, the power of information and the importance of transparency in democracies. The event was hosted by the Frontline Club, an organization started by war correspondents in part to memorialize their many colleagues killed covering war. Frontline Club co-founder Vaughan Smith looked at the rare sunny sky fretfully, saying, “Londoners never come out to an indoor event on a day like this.” Despite years of accurate reporting from Afghanistan to Kosovo, Smith was, in this case, completely wrong.

Close to 1,800 people showed up, evidence of the profound impact Wikileaks has had, from exposing torture and corruption to toppling governments.

Assange is in England awaiting a July 12 extradition hearing, as he is wanted for questioning in Sweden related to allegations of sexual misconduct. He has not been charged. He has been under house arrest for more than six months, wears an electronic ankle bracelet and is required to check in daily at the Norfolk police station.

Wikileaks was officially launched in 2007 in order to receive leaked information from whistle-blowers, using the latest technology to protect the anonymity of the sources. The organization has increasingly gained global recognition with the successive publication of massive troves of classified documents from the U.S. government relating to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and thousands of cables from the U.S. embassies around the world.

Of the logs from the two wars, Assange said that they “provided a picture of the everyday squalor of war. From children being killed at roadside blocks to over a thousand people being handed over to the Iraqi police for torture, to the reality of close air support and how modern military combat is done … men surrendering, being attacked.”

The State Department cables are being released over time, creating a steady stream of embarrassment for the U.S. government and inspiring outrage and protests globally, as the classified cables reveal the secret, cynical operations behind U.S. diplomacy. “Cablegate,” as the largest State Department document release in U.S. history has been dubbed, has been one of the sparks of the Arab Spring. People living under repressive regimes in Tunisia and Yemen, for example, knew their governments were corrupt and brutal. But to read the details, and see the extent of U.S. government support for these dictators, helped ignite a firestorm.

Likewise, thousands of Haiti-related cables analyzed by independent newspaper Haiti Liberte and The Nation magazine revealed extensive U.S. manipulation of the politics and the economy of that country. (This column was mentioned in one of the Haiti cables, referencing our reporting on those critical of the Obama administration’s post-earthquake denial of visas to 70,000 Haitians who had already been approved.) One series of cables details U.S. efforts to derail delivery of subsidized petroleum from Venezuela in order to protect the business interests of Chevron and ExxonMobil. Other cables show U.S. pressure to prevent an increase in Haiti’s minimum wage at the behest of U.S. apparel companies. This, in the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere.

For his role as editor-in-chief of Wikileaks, Assange has faced numerous threats, including calls for his assassination. U.S. Vice President Joe Biden called him a “high-tech terrorist,” while Newt Gingrich said: “Julian Assange is engaged in terrorism. … He should be treated as an enemy combatant, and WikiLeaks should be closed down permanently and decisively.”

Indeed, efforts to shut down Wikileaks to date have failed. Bank of America has reportedly hired several private intelligence firms to coordinate an attack on the organization, which is said to hold a large cache of documents revealing the bank’s potentially fraudulent activities. Wikileaks has also just sued MasterCard and Visa, which have stopped processing credit-card donations to the website.

The extradition proceedings hold a deeper threat to Assange: He fears Sweden could then extradite him to the U.S. Given the treatment of Pfc. Bradley Manning, accused of leaking many of the documents to Wikileaks, he has good reason to be afraid. Manning has been kept in solitary confinement for close to a year, under conditions many say are tantamount to torture.

At the London event, support for Wikileaks ran high. Afterward, Julian Assange couldn’t linger to talk. He had just enough time to get back to Norfolk to continue his house arrest. No matter what happens to Assange, Wikileaks has changed the world forever.

Denis Moynihan contributed research to this column.

Amy Goodman is the host of Democracy Now!, a daily international TV/radio news hour airing on more than 900 stations in North America. She is the author of Breaking the Sound Barrier, recently released in paperback and now a New York Times best-seller.