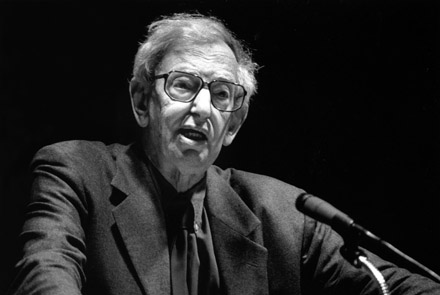

The brilliant Eric Hobsbawm died at the age of 95 on October 1, 2012. Many progressives and conservatives acknowledged that his books constituted the best introduction to modern history.

Among his most influential works were the four studies comprising the tetralogy The Age of Revolution, The Age of Capital, The Age of Empire and The Age of Extremes. The first three told the story of the nineteenth century – emphasizing the interaction between the advent of capitalism and the advance of bourgeois society and politics. The last volume narrated the history of the twentieth century, underlining, among other aspects, the problems created by ideological dogmatism while noting the progress produced by inventive combinations of diverse secular approaches.

Hobsbawm proposed that our era could be understood as having undergone three distinct periods. The first, 1914-1945, was an age of catastrophe consisting of two world wars, an economic depression and the impermanent, pivotal coalition between communists and capitalists that defeated the Nazis during World War II. The end result of this first period was the decline of Europe as the world’s central political, economic and cultural agent.

The second period, 1945-1973, was economically a golden era that produced the greatest social and cultural changes of the twentieth century including anti-colonial revolutions and the expansion of women’s rights. Pressure from radicals and Keynesian economic policies substantially reduced inequality and unemployment around the world.

The third period, from 1973 onwards, were years of crisis that brought down not only the Soviet Union but also initiated the decline of social democracy and free market economics: high levels of inequality, homelessness, poverty and unemployment returned to Western countries and — except for East Asia — were amplified in others.

Significantly this last phase demonstrated and continues to demonstrate the failure of many of the nineteenth and twentieth century’s utopian visions: socialism, nationalism and laissez-faire economics all demonstrated their limits, if not their essential weaknesses, leaving us stranded in a world that now lacks a reliable map or ideological compass by which to define human progress.

Throughout the book Hobsbawm noted that the effective political actors are those who learn from their opponents, whether intentionally or, as is more often the case, inadvertently. In particular, capitalist countries augmented their capacity and legitimacy because they were forced to reform themselves in order to deal with the threat posed by the communist world.

Likewise, at the end of the century China raced ahead economically, while the Soviet Union fell, because China successfully incorporated some free market policies into its statist project. In Hobsbawm’s vision the philosophically rigid — even when heroic — are inevitably history’s losers.

Hobsbawm concluded that, by the end of the twentieth century, “Most people in the 1990s were taller and heavier than their parents, better fed, and far longer-lived, though the catastrophes of 1980s and 1990s in Africa, Latin America and the ex-USSR may make this difficult to believe”: thus the century of tragedy was also one of unprecedented progress, that is to say, the efforts of progressives — despite their limitations, their unevenness and their mistakes — were not in vain. They pushed the globe forward even if the meaning of “forward” had become increasingly unclear by the end of the twentieth century.

Hobsbawm is often portrayed as an unrepentant communist. Yet The Age of Extremes made evident that his unrivalled historical capacity precluded intellectual dogmatism, instead favouring experiment, blend and innovation. His interpretation of the century demonstrated that the long-term pursuit of freedom requires that we remain perpetually ready to liberate ourselves from our most cherished tactics.

Thomas Ponniah was a Lecturer on Social Studies and Assistant Director of Studies at Harvard University from 2003-2011. He remains an affiliate of Harvard’s David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies and an Associate of the Department of African and African-American Studies.

Photo: The New School