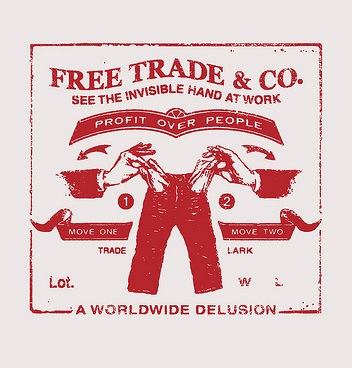

The Harper government thinks negotiating and signing various deals with all kinds of countries shows it is fulfilling its economic mandate. Nothing could be further from the truth. What are erroneously described as trade agreements or, worse — free trade agreements — end up limiting Canada’s ability to develop and create products and services for Canadians that people in other countries might use as well.

If you want to trade, you need a product or service, a market, and money to put the deal together. All the commercial agreements in the world are no substitute for having something other people want enough to buy.

How can a trade agreement be positive when it means giving up the economic tools Canadians need to make goods and produce services for use here and elsewhere? That is precisely what happened when the Mulroney Conservatives signed a deal with the U.S., the so-called free trade deal (superseded in 1994 by NAFTA).

For example, under the FTA, Canada agreed to forego export taxes on raw materials.

By penalizing unprocessed exporting, export taxes encourage domestic manufacturing. Why send raw bitumen south, when Canada could develop a manufacturing base in petrochemicals? Why allow exports of raw logs when we could be making paper and finished wood products at home?

Canada needs the freedom to impose export taxes to build a made-in-Canada economy. Ensuring benefits for companies operating abroad — not at home — is what concerns trade negotiators. Canadian citizens are supposed to adjust their lives to whatever results from more freedom for capital.

The Transpacific Partnership, the Canada Europe deal (CETA), or the some 60 bilateral talks initiated by the Harper Conservatives promise to deliver many benefits to foreign owned enterprises. Protecting the rights of foreign owners, the absentee landlords of the world, is the objective. Canadians are expected to find meaningful work, despite negative consequences for employment for many through rationalization following mergers and acquisitions.

Without any significant public discussion or input from parliament, Canada signed an investment agreement with China. The deal allows companies from both countries to carry out business in the other. In effect Canada accepts that public sector actors or SOEs are legitimate economic actors in this country.

The unforgivable contradiction accepted by the Harper government is that the FTA, then NAFTA, effectively ended the Canadian practice of establishing its own SOEs — better known as crown corporations. So while Chinese state owned companies can operate here, Canada is prevented from creating equivalent corporations.

Under the FTA, and NAFTA, Canada adopted the American thinking that state corporations were unnatural “public monopolies,” and needed to be restrained, and eliminated through privatization of assets.

Crown corporations were considered to have an unfair advantage when competing against American Transnational enterprises (TNEs). True enough, if you were an American. Of course, for Canadians, Crown corps provided a more reliable and secure service, or product, people needed at a lower cost.

Under the NAFTA or FTA, a province could bring in, say, public auto insurance, and create a crown corporation to do it. Except that with these models for future trade deals in place, after 1988, the price for creating a state enterprise became prohibitive. In order to set up the new public insurance company, as the Ontario NDP pledged to do, the province would have had to first compensate every private insurance company for the current and future expected profits it could expect to lose as a result of replacing costly private sector auto insurance, with more affordable public insurance.

Under these terms no province is prepared to establish such a scheme because it would have to pay twice to do it. Once to establish the company, and twice to pay off the existing insurance providers. Ontario gave up on the idea in 1991.

Obviously if these deals had been around before 1988, Canada could never have created the CBC or established medicare. The federal government has privatized Air Canada, CN and a host of crown corporations and public facilities in the wake of the trade deals with out benefits in affordability, or improved services for Canadians.

Canadians need to know more about CETA talks, and need the Opposition parties to push for a made-in-Canada economic strategy. After the federal NDP downplayed opposition to the Canada-U.S. trade deal in the 1988 election, splits occurred in its ranks, and, by 1993, NDP voters switching to the Liberals gave Jean Chrétien the first of three majority governments.

Adopting a modified trade option instead of a Canadian economic strategy will not work for the NDP, the Liberals or the Greens. Following the Conservative example on trade makes no sense whatsoever.

Duncan Cameron is the president of rabble.ca and writes a weekly column on politics and current affairs.