“And rich men, like emperors, have always had a weakness for tame holy men, for saints.”

A few years ago, while living in Cambridge, Massachusetts, I spent 12 months in an emotional desert. My father had died, a long relationship had ended and my teaching workload at Harvard University was more strenuous than ever. Those 52 weeks were so wearing that my doctor suggested I take sleeping pills in order to get some rest. I refused the medication so he told me that I had to find a solution within two weeks because my pulse rate was too rapid, my energy levels too low, and the bags under my eyes far too large. We scheduled a follow-up meeting for 14 days ahead and I left his office.

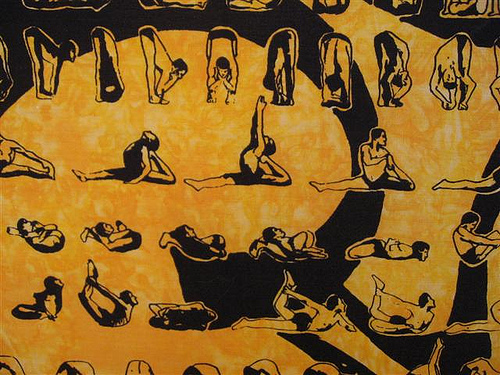

On my way home I passed by a familiar sight: the Karma Yoga studio. I had walked by the center hundreds of times over the years without giving it a second glance. This time I stopped, went in and signed up for a month of classes. I have always liked intense physical workouts — martial arts, track, and weights — but I had never immersed myself in yoga. For the next two weeks I regularly participated in an anusara class superbly taught by Elizabeth Brown. When I went back to see my physician my pulse rate had returned to normal and I decided to continue with the yoga training. I practiced anusara three times a week for six months and then started to experiment with other forms of yoga — such as core power classes taught by the also excellent Karma Longtin. Eventually I found Bikram yoga — and fine teachers such as Damien Smith — and have been a regular for the past 19 months.

Bikram’s yoga sequence consists of 26 postures, with an emphasis on both extension and compression, performed in a room heated up to 105 degrees Fahrenheit. Bikram’s 90-minute classes are probably the most difficult workouts that I have ever attempted. For the first three weeks each class brought me to the edge of absolute physical exhaustion. If we imagine the mind as a bowl of thought, then the Bikram series of postures tip the basin upside down, empty it of content, and leave little beyond the desire for survival. The point of the extreme heat is not only to increase the capacity of one’s muscles to extend but to also amplify one’s ability to create internal calm, with the idea being that if one can achieve focus under the harsh, suffocating conditions of a Bikram class then one can presumably realize it anywhere. By the end of a session I often feel physically depleted but also surprisingly mentally clear.

Two fascinating books on Bikram yoga include one Bikram Yoga: The Guru Behind Hot Yoga Shows the Way to Radiant Health and Personal Fulfilment (HarperCollins, 2007) by its founder which I will discuss in a future column, and the more recent Hell-Bent: Obsession, Pain and the Search for Something Like Transcendence in Competitive Yoga (St. Martin’s Press, 2012) by Benjamin Lorr. The two books, the first inspiring and technical, the second insightful and idiosyncratic, together offer a comprehensive look at this immensely popular yoga style.

Lorr notes that Bikram Choudhury is a guru whose talent is widely acknowledged: luminaries such as the basketball player Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and the tennis players John McEnroe and Andy Murray have publicly attested to how Bikram yoga has improved their athletic careers. Choudhury himself is a contentious figure. The most famous controversy concerns his decision to patent his sequence of yoga postures. Yoga teachers conventionally have thought of their practice as part of the spiritual heritage of humanity and therefore would have never considered patenting any aspect of yoga. Lorr points out that Bikram has not patented the postures but instead the sequence analogous to how a musician receives a copyright on the sequence of notes in a song but not the notes themselves. Bikram, to this point, has successfully sued or at least stopped any schools or teachers that appropriate his series of poses.

Bikram’s career did not begin with the goal of material wealth. He trained from the age of five onwards with one of India’s most famous yogis, Bishnu Ghosh. At the age of 13 he became the youngest person to ever win the All-India Yoga Asana Championship — a feat which he repeated two more times. At the behest of his teacher he eventually moved to the United States and opened a studio in Beverly Hills in order to spread the practice of yoga to the West. Following the Indian tradition he provided free classes, up to five per day, open to everyone including celebrities such as Shirley MacLaine and Quincy Jones. MacLaine convinced him to charge money for his sessions; up to this point he had only accepted donations for the studio. She pointed out to him that Americans appreciate things that they have to pay for more than those that are given away freely. This advice — to commodify the spiritual practice — led to the creation of the world’s largest yoga empire. Choudhury is now a millionaire many times over and his school has, as of 2011, 3,700 sites and 1,700 teachers.

Lorr emphasizes the Bikram’s well-documented peculiarities. The yogi owns a 12,000-square-foot house in the Hollywood Hills. He has 40 Rolls Royces in his garage. He wears shirts that have tigers and flames on them. He tells students that he has no need for sleep, that he was the first to conceive of the disco ball, that he helped start Michael Jackson’s career, that he was close friends with Elvis, that he cured President Richard Nixon’s phlebitis and that Ronald Reagan phoned him to ask for advice about his daughter. Choudhury consciously or unconsciously understands — like P.T. Barnum and other American entrepreneurs before him — that the more extravagant the tale the larger the box office.

These theatrics are all the more amplified when contrasted with the adulation of a few of his followers. In the autumn of 2010, Lorr attended Teacher Training in San Diego with 380 other students each paying $11,000 for the nine-week course. During orientation a senior teacher told the students that Bikram is a fully realized human. Another teacher tells them that Bikram will see through each of them and understand everything about their past and future immediately. A third teacher tells them that Bikram is impossible to perceive and that all they will witness is “a mirror.” When Choudhury actually steps onto the stage the first thing Lorr hears from him amidst the ecstatic applause is “I am going to make you rich!” He then walks up and down the stage, looks to the audience and asks, “Is it hot in here?” He takes off his jacket and continues, “Should I take off more, ladies?” In response to the shrieks of approval, the guru strips off his clothes revealing the physique of a man half his age.

Lorr’s book can be interpreted in various ways, with the most obvious being his disenchantment with Bikram the man. The yoga teacher is presented as someone who is clearly a guru but very far from being a saint. Lorr’s disappointment emerges however because of a far more profound unspoken dynamic at work. The truly tragic story at the heart of this book is the one of a young idealistic spiritual master who descends from the mountain in order to liberate the world but is then slowly but surely transformed by the society he had hoped to alter. The story of Bikram is analogous to the parable told by Tolkien: the ring of power offers unlimited freedom but is potentially lethal to its bearer.

Bikram Choudhury is a technical genius: his sequence of postures has attracted millions of adherents because it does substantially improve the physiological well-being of a certain anatomical type and temperament. The Rolls Royces in his garage were initially old wrecks that he found and personally reconstructed. He has done the same with many people’s bodies. For advice in the physical realm, I consult medical doctors, yoga teachers and others who are expert at renewing the body. For guidance on moral renewal, by contrast, one must look to philosophers, theologians, charities, human rights institutions and political activists pursuing various forms of social emancipation.

Thomas Ponniah is an Affiliate of the David Rockefeller Center for Latin America Studies and an Associate of the Department of African and African-American Studies at Harvard University.

Photo: elidelaney/flickr