When more than 200 bystanders, pedestrians and cyclists were first surrounded by a cordon of police officers on a stretch of downtown Toronto June 27, 2010, during the G20 summit, they didn’t realize they would become a part of political strategy that has its roots dating back two and a half millennia.

Police kettling can be traced back to the military tactic of encirclement, according to Scott Sørli, who researched the idea and has collected hundreds photographs of police kettling from around the world.

Sørli — who teaches architecture in Toronto and completed a Masters of Design Research at the University of Michigan in 2012 — says kettling is the child of the military strategy of encirclement.

Fast forward to June 8, 1986, Hamburg, Germany and encirclement has a new name. On that day, more than 800 people were “kettled” during a protest to contest the state withdrawal of the right to protest. They were held up to 13 hours with no bathroom breaks, food or water.

Sørli became intrigued by police kettling after the G20 incident and wrote about it this year for the architecture/landscape/political economy journal Scapegoat and the Weimar-based journal Horizonte. His work was most recently exhibited at Winnipeg’s Atomic Centre as part of “A Total Spectacle.”

As an architectural designer, how did you become interested in this?

I consider police kettling a cultural-spatial phenomenon in which the police use a line of their bodies to encircle and hold in place several hundred people over an extended duration of time.

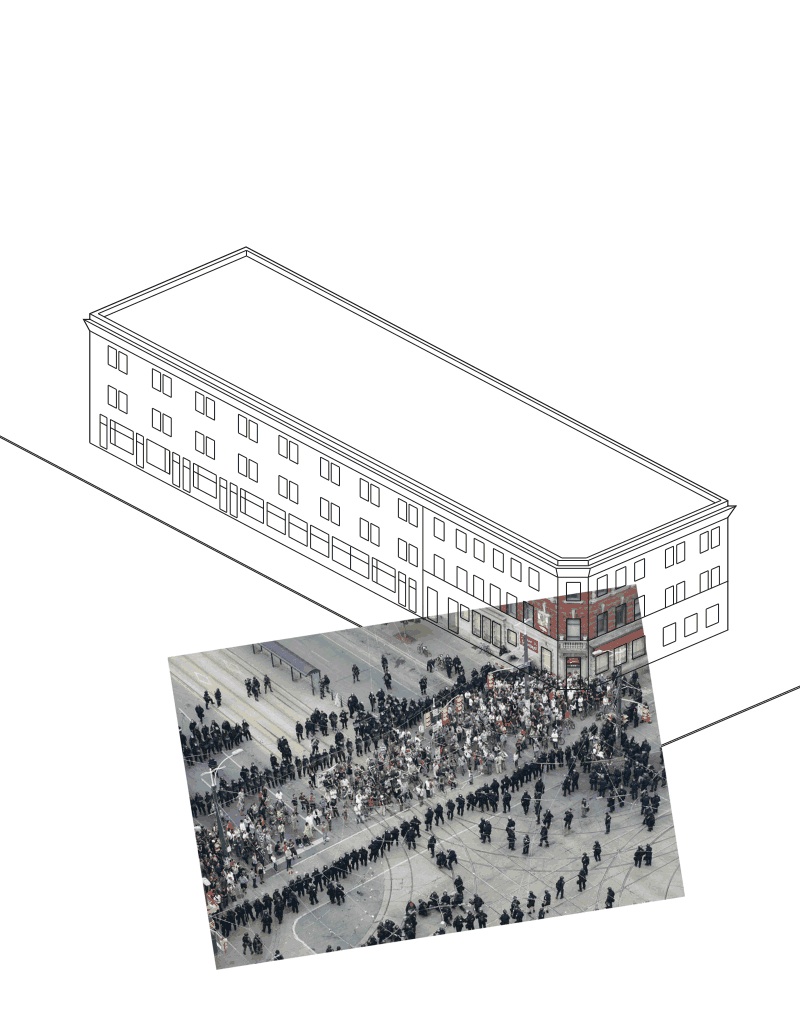

Looking at it with an architect’s eye, police kettles are an urban event that requires adjacent building façades as a portion of the containment ring. In the case of the G20 Toronto incident, a global fast food outlet and a branch of one of the “big five” banks bracketed the people caught in the kettle.

A random selection of 200 bystanders, cyclists, pedestrians and shoppers were trapped for several hours. The specific crossing they were confined in was deliberate when you consider the section of road they were held on.

The configuration of the parallel police cordons crossed Spadina Avenue, which is a wide boulevard with streetcar tracks down its centre, rather than the narrower crossing of Queen Street. This was used as an experiment to demonstrate the viable length of the police line, which was shown to be any length desired, as long as sufficient police are on hand to cycle through their shifts.

I’d like to emphasize that not one citizen from this kettle was convicted of any charge, while over 70 police officers at the G20 were subsequently disciplined for removing their ID badges, which was contrary to police policy. Police Superintendent Mark Fenton, the commanding officer who ordered the kettling, has since been charged with misconduct. There was no reason for the kettle. It is clear that its purpose was as a live training exercise.

What were the most interesting discoveries you made in your research?

Kettling is a mass ornament, to use Sigfried Kracauer’s term, that is external. While the police have their procedures, the individuals kettled behave no differently than water molecules do in making a wave. And, just as watching the waves crash against the beach over and over, the mass ornament of police kettling has a beauty all its own.

The membrane of a police kettle consists of the bodies and minds of the police, as well as inorganic material such as shields, truncheons, polycarbonate and Kevlar. Metal elements, such as crowd-control fencing or steel barricades can also become part of the police line.

During the Occupy Wall Street protests, plastics were deployed as barriers because of their light weight, flexibility, low cost and ease of use. Watching it unfold, the barriers bend and sway during the interaction between the yellow-clothed and black-clothed individuals. It is a social exoskeleton.

This reminds me of something Eyal Weizman said about “materialization of time [where] matter is not only as an imprint of relations, but as an agent within the conflict.”

And it makes me wonder, did the workers who made these materials know the products would be used this way?

What about yourself — how do you feel that buildings, physical elements are being used this way?

I try to not to feel anything about it. To examine police kettling, I detach and try to look at it from an aesthetic, technological and typological point of view. Of course, I’m appalled by it. I think it’s a completely fascist configuration and it worries me very much.

To oppose it, it has to be described, and moral judgment gets in the way of understanding. I don’t want to tell people what to think and I don’t want to manipulate them emotionally. I’d rather they make their own conclusions and I think that’s way more powerful.

You created an exhibit about this, so what did that look like?

My work was part of “A Total Spectacle” at Winnipeg’s Atomic Centre. The show examines corporatism in its many forms as we are embedded within it. My exhibit was composed of photo montages of the Queen and Spadina kettle and the Westminster Bridge kettle. The images in my montages are carefully edited together. I chose the frames to mimic those in the Degenerate Art Exhibition of 1937. It was the curator’s idea to hang them with those same chains.

The curator, Milena Placentile, created an exhibition that made a convincing case for what I see as the historical parallels between the Weimar Republic and our current historical moment.

I’d like to refer to her exhibition statement, in which she writes:

“Today’s spectacle takes many forms, from big budget events and entertainment to ever-present news media and advertising. It displays lifestyles we should envy and tells us how to succeed … It sensationalizes violence while showing us what might happen if we rock the boat. It is power represented through repetitive sights and sounds, stereotypes and clichés, and other social signals about wealth, fame, and technology, and it all serves to influence general opinion and behaviour to support a consumer society and those who profit from it the most.”

What is the “future” of kettling?

There’s a kind of morphing going on. Typically, a police kettle is static, but recently we’ve seen the wander kettle, which is not. In this case, police arrange themselves in front of, to the sides of, and behind protesters as they march. Once encircled, the police then control the route, starting and stopping the march at will.

This leads to the new phenomenon of bridge kettling. The earliest documented case of this occurred on the Pont de la Guillotière in Lyon, on Oct. 20, 2010. A wander kettle is deployed to a large bridge and detained over a waterway. Water acts as a barrier without appearing to be one, and at the same time, the potential of property damage to private commercial buildings is pretty much eliminated.

In the Westminster Bridge kettle of Dec. 9, 2010, young students protesting tuition fee increases experienced nightfall and plunging temperatures while held over the open water of the Thames as the vote on those increases in the facing House of Commons was being executed. If you check out the photograph, a light on the bridge has been disabled so the police are backlit and appear to be one amorphous black mass — more menacing.

If a police kettle contains, holds and then releases people — what’s the point?

The purpose of police kettling is to deliver sensations and those sensations are delivered for political reasons. Whether they are physical or emotional, the final outcome is designed to disempower the citizenry.

Once a police kettle has been put and held in place, the performance begins: the sun goes down and it gets dark, temperatures fall and it gets cold, relative humidity rises and, often, it rains. The atmosphere is regularly intensified with tear gas and pepper spray, as well as electrical shock effects.

At a lower level, people experience discomfort through the prohibition of drinking water, consuming food, excreting waste and, for women, changing a tampon or pad. So those being kettled experience anxiety, fear, anger, helplessness, and despair and so on.

So kettling is a form of performance, i.e., political theatre?

Kettling reminds me of Brecht and of Kafka — they operate in clearly aesthetic realms and their work is meant to incite political change.

Because of the indiscriminate nature of police kettling, it is an example of collective punishment. As the roll-out of economic austerity programs continues around the world with a lack of discrimination (against the middle and lower classes, in any case), kettling as a repressive technique will increase, intensify and mutate.

As Walter Benjamin wrote in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction: “Efforts to aestheticize politics culminate in one point. That one point is war.”

June Chua is a Toronto-based journalist who regularly writes about the arts for rabble.ca.

Images courtesy of Scott Sørli.