“I don’t have to be who you want me to be.”

– Muhammad Ali

There are a number of fascinating interviews between the 20th century’s greatest boxer Muhammad Ali and Howard Cosell, one of the most intelligent sports commentators of the era. In one conversation, Cosell asks Ali, “Who would you like to fight?” Ali replies, “I would like to fight whoever you think is the best, the number one man…” Cosell, responds with resignation and awe, telling the young man, “I am not sure that there is anyone left really for you to fight.“

No athlete in the past century has captured the hearts of progressive activists, writers and commentators around the world more than Muhammad Ali. Ali was born Cassius Clay in 1942 in Louisville, Kentucky. In 1954 his new bicycle was stolen and he reported the theft to Joe Martin, a white police officer, telling him that he was going to find the thief and beat him up. Martin advised the 12-year-old that he better take some boxing lessons before getting into a fight. Good advice: six years later Cassius Clay won a gold medal in the 1960 Rome Olympics. Upon returning to Kentucky, the young man was stunned to discover that Olympic victory did not translate into equal rights; he was still treated as a second-class citizen, and for example was not permitted to eat in many restaurants in the segregated South. In 1961 he began to attend meetings held by the Nation of Islam and in 1964, after beating Sonny Liston to win the World Heavyweight title, changed his name to Muhammad Ali.

For the next three years, he was undefeated and considered by many to be the greatest fighter of all time. In 1966 he was drafted to fight in Vietnam but refused as a conscientious objector. While many Americans repudiated the war, Ali was the most famous and the one who in the short-term lost the most. From 1967 onwards, State Athletic Commissions across the United States rescinded acknowledgements of his heavyweight crown and withdrew his boxing license, preventing him from fighting competitively or in exhibition matches. A federal grand jury in Houston, Texas indicted Ali; he was released on bail, but on the condition that he was not allowed to travel outside the United States. From 1967 to 1970, Ali went from campus to campus, 200 in all, giving speeches about his views on life and defending his decision not to support the Vietnam War. In 1971 the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously reversed Ali’s conviction. He returned to boxing and in 1974 defeated George Foreman in Kinshasa, Zaire regaining the World Heavyweight crown — a battle immortalized in the Oscar-winning documentary When We Were Kings and in Norman Mailer’s superb account The Fight.

A more recent documentary, The Trials of Muhammad Ali, directed by Bill Siegel, focuses on Ali’s relationship to Islam, his decision not to fight in Vietnam, and the consequences of that decision. The film is filled with insightful discussions with Ali’s brother, one of his past loves, a daughter and members of the Nation of Islam. The movie also has entertaining footage of Ali in all his dimensions: the dazzling fighter, the clever self-promoter, the perpetual clown, the magician — Ali loved doing magic tricks — and the principled man who stood up to the U.S. government at a time when the vast majority of the public supported the Vietnam War, hated the Nation of Islam, and denied African-Americans equal legal and cultural rights. It is difficult to imagine the most privileged of our contemporary celebrities giving up any of their money, their fame, or the recognition of their achievements for the sake of principle, conscience and integrity.

The film is enjoyable, interesting and worth seeing. It is nonetheless selective in its choices. It focuses on the boxer’s relationship to Islam without noting that his cornerman Bundini Brown was Jewish, his trainer Angelo Dundee was Roman Catholic, and the entourage that he travelled with — more than 50 people by the time of his 1975 fight against Joe Frazier — included people of every colour. Ali transcends the boundaries of every image imposed on him.

In his autobiography Soul of a Butterfly — of which there is a touching audio version read by the late Ossie Davis — Ali notes that he now sees his boxing career as simply a prelude to his real work of bringing peace to the world. Ali has contributed to numerous charitable organizations such as the Special Olympics, UNICEF, and Project A.L.S. and has worked as a United Nations Messenger for Peace. He has received numerous awards for his boxing skills and his humanitarian work outside of boxing: in 1999 he won the Sports Illustrated award “Sportsman of the Century.” In 2000 the Muhammad Ali Boxing Reform Act was passed by the U.S. government to reform unfair practices in professional boxing. In 2005 president George W. Bush — of all people — acknowledged Ali’s contribution to the country, awarding him the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Ali, despite the Parkinson’s disease which has crippled his ability to speak, of course had the last word. Bush whispered something to Ali and the fighter looked back at him, placed finger to head, and did the “are you crazy?” twirl.

Thomas Ponniah is an Affiliate of the David Rockefeller Center for Latin America Studies and an Associate of the Department of African and African-American Studies at Harvard University.

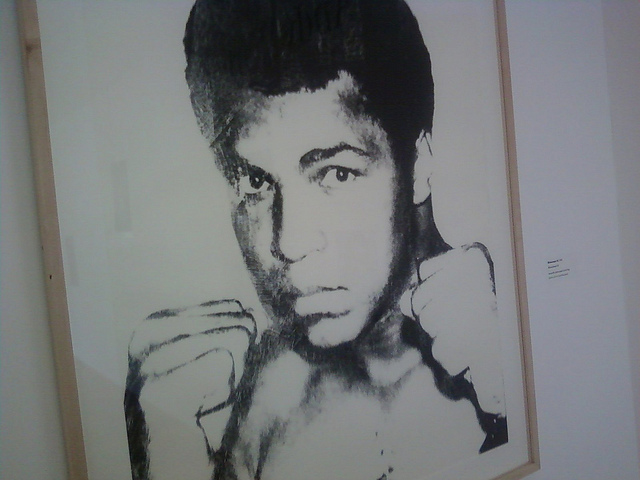

Photo: Visionello/flickr