A futuristic article by Kim Stanley Robinson, “How Science Saved the World,” can be found in the February 2000 issue of the prestigious journal Nature (Vol. 403, p. 23). Looking 1,000 years into the future, Robinson reviews two books written around 3,000 AD: Science in the Third Millennium by Professor J. S. Khaldun; and Scientific Careers 2001-3000, written by a computer named “Ferdnand.”

Professor Khaldun propounds an ambitious theory of history as a clash between feudalism, capitalism (with its lingering feudal elements), and permaculture. He gives particular attention to the dangerous “overshoot” period of global warming and extinction, during which humanity’s reproductive success and primitive technology severely damaged Earth’s carrying capacity.

According to Khaldun:

“Capitalism attempted to maintain a hierarchy in which science would serve as pet monkey, cranking out new commodities and increasing lifespans. Science resisted this impulse not only because of the practical danger of the overshoot to the progeny of scientists, but also because science itself would be threatened if the residual elements succeeded.”

Scientists eventually transformed capitalism into a more rational, universal, lawful and pragmatic set of practices that came to be recognized as “permaculture.” Scientific Careers 2001-3000 provides extensive graphs and tables documenting the careers of scientists who worked during the “overshoot”: those who contributed to humanity’s survival, and those who did not. In this statistical work, the ultimate triumph of permaculture is seen as the sum of small individual positive actions, rather than as the grand battle envisioned by Professor Khaldun.

Fifteen years into the Third Millennium, what is the current state of the relationship between permaculture and science?

Permaculture — agriculture based on natural systems, with a strong emphasis on tree crops and water management — has come a long way since its debut at a call-in program on a public radio station in Melbourne, Australia in 1976. The crusty and entertaining views of one of its founders, Bill Mollison, are enshrined in a series of pamphlets (the Permaculture Design Course Series) still available online. These pamphlets offer Mollison’s personal history of the back-to-the-land movement, interspersed with startlingly incisive observations about successes and failures in applying ecological principles to the growing of food. Permaculture, with its links to intentional communities, may represent the most enduring legacy of the counter-culture of the 1960s and 1970s.

R.S. Ferguson and S.T. Lovell, in “Permaculture for agroecology: design, movement, practice, and worldview” (Agronomy and Sustainable Development, 34: 251–274, 2014), characterize permaculture as a social movement with broad international media attention and considerable potential to help society’s transition to sustainability. However, these authors lament permaculture’s isolation from science — the absence of scholarly research about permaculture, and the neglect of science within the permaculture movement itself. They criticize “overreaching and oversimplifying claims” made by permaculture’s adherents, and the lack of any replicated scientific research on permaculture’s impacts.

Others offer similar comments. In “Feeding and healing the world,” (Science Progress, 95: 345-446, 2012), Christopher Rhodes writes, “there is overwhelming evidence both that [permaculture] methods work and they may offer the means to address a number of prevailing environmental challenges… What is lacking is a proper scientific study, made in hand with actual development projects.”

There are also voices calling on the permaculture movement to embrace political action — to engage in the struggle envisioned by Professor Khaldun. Jung Suh’s article, “Towards sustainable agricultural stewardship: Evolution and future directions of the permaculture concept” (Environmental Values, 23: 75-98, 2014), calls for “more aggressive environmental-policy measures that support permaculture and internalise the non-market value of reduced fossil-fuel energy consumption and waste recycling.” And Olivia Miller’s 2014 thesis, “Evaluation of the permaculture movement and its limitations for transition to a sustainable culture,” calls on the movement to “address barriers created by existing political structures in order to be a relevant and viable model for sustainable transition.”

In “When science goes feral” (NJAS – Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences, 59: 7–9, 2012), F.A. Morris cites permaculture as the prime example of how ecology has “escaped from the confines of academia.” He says the popularity of permaculture “rode the growing communication revolution” from the 1970s onward:

“Now its terms and techniques spread virally through YouTube videos, support and information exchange bulletin boards, blogs, national societies and local networks; its businesses and courses proliferate…. This movement has built an ecological culture with such strong beliefs and identity that it has been considered cult-like and thus rarely manages to come in from the fringe.”

Yet Morris also views permaculture in a positive light, overall: “It gives people outside academia a sense of ownership and increased understanding of their surroundings — necessary for the healthy survival of humanity and an intact global ecological system.” He concludes, “This is something valuable; now it is up to science in general and universities in particular, to creatively capitalize on this future.”

Ole Hendrickson is a retired forest ecologist and a founding member of the Ottawa River Institute, a non-profit charitable organization based in the Ottawa Valley. This article was also published in the Ottawa River Institute’s Watershed Ways column.

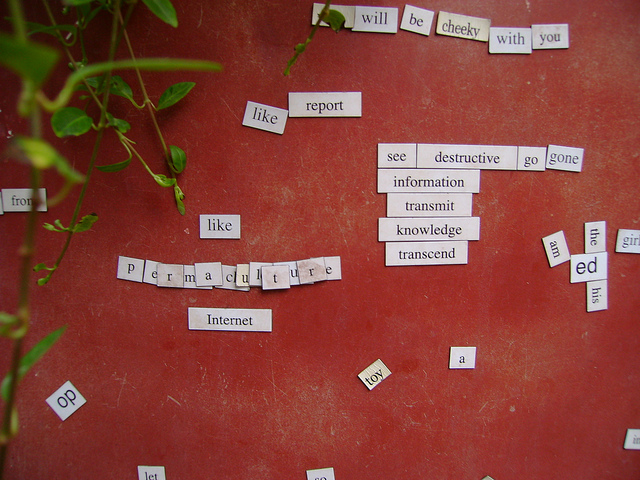

Photo: London Permaculture/flickr