Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Was there any concrete economic reason for Stephen Harper to call Stephen Poloz this week, as global stock markets continued their gyrations? And then to have his office subsequently issue a cryptic and rather foreboding statement about the conversation?

Of course, prime ministers and central bank governors talk to each other every now and then — but these conversations, for obvious reasons, are rarely publicized. And since we are in an election campaign, the meeting was all the more odd.

Poloz himself has no control over the actions of the markets. And his response to any macroeconomic damage that results is limited to monetary policy adjustments (the next Bank of Canada interest rate decision is September 9), over which the prime minister is not supposed to have sway.

The prime minister himself can’t do anything about the market chaos, either. Once the writ has dropped, the government switches into “caretaking” mode, and has no discretionary policy-making authority.

And there was nothing in this week’s gyrations, stomach-churning as they were for the buy-low-sell-high crowd, that indicated a need for emergency action by either the government or the Bank. If anything, it was “par for the course” for speculative markets, which are always driven by alternating waves of greed and fear.

Political optics

So what was the point of the call? Political optics, obviously — which explains why the PMO’s subsequent spin effort was more important than the phone call itself.

Politicians always follow the “look busy” rule: when bad things happen, they have to be seen to be responding, even if there is little likelihood their actions will have any effect. But in this case, Harper was motivated by an additional strategic judgment. Perversely, with his re-election campaign sidetracked by ongoing revelations in the Duffy/Wright case, the prime minister actually wants Canadians to worry about the economy. Conservative strategists hope that will undermine voters’ willingness to consider an alternative government, playing into the traditional frame that Conservatives have the strongest economic “credentials.”

[That claim itself, of course, is wildly at odds with the statistical record, as confirmed by Unifor’s recent report. We compiled historical data on 16 conventional economic indicators going back to 1946, and found that Canada’s economy performed worse under Harper’s leadership than any other postwar prime minister — and lagged most OECD countries during Harper’s tenure, as well. See the full report Rhetoric and Reality, a short two-page summary, and a four-minute video.]

If Canadians become more focused on economic risks, the thinking goes, they will pay less attention to the Duffy scandal, and they will be more cautious when casting their ballot. In this worldview, it actually helps the Conservatives to talk up bad economic news. This marks a U-turn from earlier messaging, when Conservatives first tried (futilely) to deny the economy was in any trouble at all. With the negative numbers piling up around them, the Tory spin machine has decided to throw in the towel, and try to make a silk purse from this sow’s ear. They now want to emphasize the gloomy economic outlook (while simultaneously, of course, evading blame for contributing to it at all).

Reading between the lines of the PMO statement, therefore, its true message was this: “Things are scary, Canadians, very scary. But Stephen Harper is a man of action — a strong, stable leader. When markets melt down, he makes the call.”

It was a transparent political stunt, but most media outlets lapped it up as a sidebar to their coverage of the day’s market gyrations. [A few reporters wondered aloud about its real significance, and about what it meant for the independence of the central bank — more on this below.]

Emphasizing the negative

Ironically, then, ever since Thomas Mulcair nailed Mr. Harper in the Maclean’s leadership debate on Canada’s apparent recession, Conservatives seem to be giving up on boasting about Canada’s economic record under their rule (which was an uphill task anyway). They now emphasize dark risks ahead, to strengthen their frame that any change in government would be too “risky.” But this upside-down politics, can have upside-down macroeconomic consequences, too.

Economists understand well that in a market economy, the psychological sentiment of economic agents can have real economic effects. If consumers and businesses feel confident about the future, they are more likely to spend on major purchases and capital investment — thus helping to usher in the good times they were expecting. On the other hand, when pessimism sets in, they sit on their wallets. Worried consumers put off major purchases, businesses postpone capital spending. And those actions alone can bring about a macroeconomic downturn. Fear becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

This is why governments and economic officials are loathe to be gloomy in their public statements about the economy. They hate to use the “r-word” (recession). Mr. Poloz himself bent over backwards in his last Monetary Policy Report to not use that term — even though the Bank’s own numbers (projecting negative GDP growth for both the first and second quarters of 2015) suggested a recession was indeed already underway. Instead, public officials are normally sanguine and rose-coloured in their public pronouncements, hoping to incrementally shift consumer confidence with their cheeriness, and thus spark more spending. [A ridiculous extreme of this approach was provided when George Bush blithely encouraged Americans to go shopping in the days after the 9-11 terrorist attacks.]

Now, however, the reverse is occurring. Because of a narrow, perverse political calculation, Conservatives have decided that it is to their advantage for Canadians to be as worried about the economy as possible. And so they are actively playing up the risks. The call to Poloz was part of that strategy: Things must be bad. Why, the prime minister even had to call the central bank governor!

What’s more, the PMO’s own statement then ran through a full litany of all the bad things that lie ahead: decline in global stock markets, decline in commodity prices, slowing growth in China and emerging markets, and potential impacts on Canada’s economy. Instead of boasting about Canada’s successes under Conservative leadership, the PMO went to great lengths to show how bad things could get.

Harper added to the sense of lurking danger with his own comments at a campaign event in Quebec, referring darkly to the prospect that more dramatic crises might lie ahead. “We have a range of tools with which we can respond were we to face some obviously much more serious circumstances.” What tools? What circumstances? He would not specify, preferring simply to leave an oblique but dark cloud hanging over the electorate’s heads.

This is a very unusual tack for a national leader to take during a time of economic instability. Given the potential macroeconomic significance of his own statements, emphasizing the negatives in the outlook could even be argued to incrementally make matters a bit worse. [I would not overstate that effect, however, since consumer spending decisions are not really that influenced by the statements of their fearless political leaders. Americans did not actually run out to shop after Mr. Bush’s exhortation.]

So-called central bank independence

Another controversial aspect of Mr. Harper’s call to Mr. Poloz is the implication for the Bank of Canada’s political independence. While the Bank of Canada communicates with the government (normally through the finance minister, not the prime minister, though Joe Oliver was nowhere to be seen in this week’s theatre), both sides proclaim the Bank’s operational independence from the day-to-day politics of Ottawa. And Conservatives regularly invoke that idea when it suits them.

For example, in the latter days of the 2011 election campaign, as Jack Layton’s Orange Wave was gathering momentum, Harper and then-finance minister Jim Flaherty jumped all over Mr. Layton for allegedly violating the sacrosanct principle of central bank independence. Layton had responded to a reporter’s question about interest rates, indicating it would be better for Canada’s economy if they stayed low. Harper and Flaherty denounced this statement violently, calling it a “rookie mistake” that threatened the independence of the Bank. Layton quickly issued a clarification confirming that he, too, accepted the doctrine of central bank independence. Yet this isn’t the first time in the present campaign that the Conservatives themselves have trespassed on traditional Bank of Canada terrain. On July 22 Joe Oliver publicly rejected the use of quantitative easing (QE) in Canada (the unconventional credit-expanding strategy that has been used successfully in the U.S., the U.K., and now Europe) despite dimming economic projections here. Decisions about the use of QE should, in theory, be the purview of the central bank. Several economists publicly questioned Oliver’s statement, noting that it throws into question the Bank’s future decisions on monetary policy.

I am not a great believer in so-called “central bank independence.” It is largely an institutional edifice that has been erected during the era of neoliberalism to insulate the often-painful actions of central banks from popular opposition. Central banks are not truly “independent”: their worldviews and actions are clearly shaped not only by the preferences of the governments they nominally work for, but more importantly by the financial industry and the interests of financial wealth. [The Bank of Canada’s website summarizes its mandate, not exactly accurately, as working “to preserve the value of money by keeping inflation low and stable.” That is hardly a balanced or independent perspective on Canada’s economic priorities.]

But Conservatives cannot have it both ways. Mr. Harper went further than Mr. Layton. He didn’t just express a view on monetary policy during an election campaign. He actually used the Bank of Canada Governor (like the hapless Boy Scouts from last week’s botched photo-op) as a mere prop in a campaign event. For his own credibility, I hope that Mr. Poloz is equally willing to take a call from Mr. Mulcair and Mr. Trudeau in coming weeks. They have as much legitimate reason to speak with him (and to better ends) than Mr. Harper did.

Jim Stanford is an economist with Unifor.

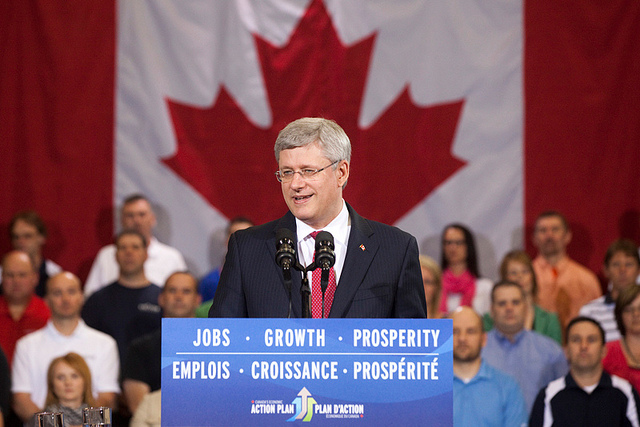

Photo: pmwebphotos/flickr

Chip in to keep stories like these coming.