rabble is expanding our Parliamentary Bureau and we need your help! Support us on Patreon today!

In most history of the left, 52 per cent of the population tends to disappear. Until fairly recently, for example, the U.S. civil rights movement histories were completely male-dominated, though that neglect is slowly being reclaimed as activists like Diane Nash, Ella Baker, Amelia Boynton, and Fannie Lou Hamer, among many others, become long-overdue subjects of studies on the era.

Even when the movement did have high-profile female names, their true role was often watered down to fit within “respectable” notions of femininity. For example, the story of Rosa Parks was treated as that of a quiet seamstress who was just tired and did not want to give up her seat for a white man. In fact, as documented in The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks, she was a long-time activist who was justifiably angry, and a fierce NAACP leader and community organizer.

It’s no mistake that the second wave women’s liberation movement largely grew out of and in reaction to mistreatment of women within the ranks of the civil rights and anti-war movement during the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s (a persistent problem that underlies our still imperfect networks to change the world). Indeed, if the men who wanted to change society could not allow a role for women beyond keeping the home fires burning, doing the typing, and keeping the coffee warm, what was the point of replacing the old boys’ network with the younger boys’ club?

Resistance films

With such thoughts in mind, I’d like to recommend two very good films about our collective history for your holiday viewing. The first, Suffragette, is a compelling look at the sacrifices of a group of working-class women during the British struggle for the vote. While the film generated controversy because of some unfortunate marketing efforts, as a story of the challenges inherent in struggles which challenge core foundations of unequal societies, it is compelling, provocative and very contemporary.

The second is Trumbo, a tribute to the prolific political screenwriter and novelist Dalton Trumbo, who penned one of the best anti-war novels of all time, Johnny Got His Gun. If you’ve enjoyed films from Roman Holiday to Spartacus, Papillon to The Brave One, Our Vines Have Tender Grapes to Kitty Foyle, there’s a reason: Trumbo wrote them, along with scores of other works (many with a pseudonym, or front, during the blacklist era). He was also a forthright political activist and unashamed social critic who courageously took on the witch hunters of his day with a combination of subversive humour, dogged determination, and an enormous store of writing talent.

Like Suffragette, Trumbo is an enjoyable film for those inspired by stories about fights against injustice. But like Hollywood itself, Trumbo is a very male film about a chain-smoking, heavy-drinking, Benzedrine-addicted writer who sits in his bathtub and cuts and pastes his scripts while he treats his family as appendages. While the film is sympathetic to family members who are rightfully miffed about how they’re treated, the emotional through-line is that we will forgive him his quirky trespasses.

In his poem To Posterity, playwright Bertolt Brecht (or one of the women whose creative work he is alleged to have cribbed) summed up the conundrum faced by many who try to change the world while remaining decent human beings:

Even the hatred of squalor

Makes the brow grow stern.

Even anger against injustice

Makes the voice grow harsh. Alas, we

Who wished to lay the foundations of kindness

Could not ourselves be kind.

Hopefully, we are evolving to a point where we do not invoke such poetry to overlook or justify our own very human frailties and prejudices. That said, viewing Trumbo does open the door to a wider discussion about gender, especially with respect to the notion of Hollywood heroism. Indeed, on those rare occasions when we celebrate women resisters in a Hollywood film, it’s often in part because certain physical accoutrements play a key plot role (think Erin Brockovich and her mammaries). Similarly, treatments of women under the blacklist are rare, though blacklisted screenwriter Walter Bernstein’s film, The House on Carroll Street, is an excellent exception.

Women under the blacklist

Those who sit through the final credits of Trumbo will learn that the blacklist was not merely a Hollywood phenomenon, but one that inflicted misery on thousands of people from all walks of life during the ’40s and ’50s: teachers, labourers, government employees, anyone suspected of being lesbian or gay, those who stood against lynching or opposed atomic weaponry. The culture of fear (much like the one we see today) infected public and private life, employing the Commie Bogeyman to significant effect both in the U.S. and, to a quieter extent, in Canada, where members of the labour movement, especially, were subject to purges, violent beatings, and exile if suspected of Red leanings. In addition, the Canadian government waged an internal war against anyone suspected of non-heterosexual leanings.

Underneath the Leave it to Beaver exterior, the Red Scare era produced an inquisition resulting in an unending spate of suicides, heart attacks, marriage breakups, exile and financial ruin. As the blacklisted screenwriter Alvah Bessie wrote in his 1965 Inquisition in Eden:

“[I]in the roll call of victims of the proliferating local, state and national witch-hunting committees, there are many who cannot answer. Their premature deaths from ‘natural’ causes and from suicide may be laid directly or indirectly at the doors of these inquisitorial outfits.”

But our history mainly remembers the men hauled before the inquisitorial House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC): Pete Seeger, Paul Robeson, the Hollywood Ten, Zero Mostel. Less remembered are the many women who suffered blacklisting, from the witty writer Dorothy Parker and Lillian Hellman (whose Scoundrel Time is an excellent history of the period) to Gale Sondergaard (Bride of Frankenstein) and Mady Christians (I Remember Mama), whose early death was attributed to the stresses of the blacklist.

One of the first high-profile witnesses called before HUAC when it began in the 1930s was the indomitable leader of the Federal Theatre Project, Hallie Flanagan. She was a brilliant witness who, like Trumbo, had a gift for words. When asked by House Un-American Activities Committee about her work, Flanagan famously replied: “Since August 29, 1935, I have been concerned with combating un-American inactivity.”

“Inactivity?” an incredulous committee chairman asked.

“I refer to the inactivity of professional men and women; people who, at that time when I took office, were on the relief rolls, and it was my job to expend the appropriation laid aside by congressional vote for the relief of the unemployed as it related to the field of the theatre, and to set up projects wherever in any city 25 or more of such professionals were found on the relief rolls.”

Disloyalty to patriarchy

While Flanagan was in the hot seat because the Federal Theatre Project was engaged in allegedly outrageous behaviour (from employing African-Americans to producing works that questioned the economic roots of the Depression), there was another theme in the questioning faced by herself and many of her sisters in government service. Her alleged disloyalty was not merely disobedience to the dictates of the Red Scare; it was, by her very presence as an accomplished woman in government, disloyalty to patriarchy.

One could be called before a “loyalty board” or congressional committee for such offences as being a “premature anti-fascist” who supported Spanish refugees while Spain was mercilessly attacked by Hitler, Mussolini and Franco, or for protesting segregation or signing a petition for peace. Indeed, it was clear that HUAC and similar bodies were aiming to roll back social and economic gains made by grassroots movements of the 1930s (much like the bogeyman of terror is used to justify repression against similar movements today).

But as University of Iowa professor Landon R.Y. Storrs points out in her excellent history, The Second Red Scare and the Unmaking of the New Deal Left, misogyny played an important role in how HUAC and other witch-hunting bodies carried out their work. One congressional committee complained, for example, that there was union trouble because of female attorneys working at the National Labor Relations Board. As one conservative congressman argued:

“Those girls who are acting as reviewing attorneys for the Board are fine young ladies. They are good looking; they are intelligent appearing; they are just as wonderful, I imagine, to visit with, to talk with, and to look at as any like number of young ladies anywhere in the country, but the chances are 99 out of 100 that none of them ever changed a diaper, hung a washing, or baked a loaf of bread.”

Storrs’ history uncovers a pattern of government harassment of women who played key roles in carrying out New Deal policies, as well as targeting of women who led the very effective consumer movements of the 1930s that, because of the Red Scare, went from demanding strong regulatory action and reduced working hours and minimum wages for women to a much narrower focus on product testing. Congressmen and a Hearst-dominated press consistently delivered gender-derisive comments as part of the 1940s Red Scare, calling Washington, D.C. a “femmocracy” of women who were shockingly able to support themselves; brazenly insisted on keeping their maiden names after marriage; and were “sex-starved government gals” who, in a tired myth still repeated today, were unhappy because they hadn’t nabbed a man, a crib, and a country home with white picket fence.

Women disproportionately accused

Storrs points out that while women made up three per cent of high-level government employees, they “seem to have comprised about 18 percent of high-level cases” with respect to loyalty accusations. The current of woman-hatred in the Red Scare years played a complementary role to the larger social shifts that pushed women’s role models away from Rosie the Riveter, the working woman who helped win the war, to the wife of Father Know Best.

Along the way, any woman who was single, or different somehow, became suspect. The best-selling 1947 book Modern Woman: The Lost Sex, cried out that “agents of the Kremlin abroad continue to beat the feminist drums in full awareness of its disruptive influence” on Soviet enemies. As Storrs points out, women suspected of being Communist were either portrayed as:

“[D]evoid of femininity or as exploiting their femininity in order to serve the Soviet cause. Unfeminine women appeared as ‘mannish’ lesbians, as robotic workers who competed with men at work rather than taking care of men at home, as bad mothers whose sons became dancers (i.e., homosexuals), and as domineering, even murderous wives.”

Ultimately, women were just plain dangerous: “a woman who appeared to be an innocent worker, a pretty date, or a loving mother might in fact be a Communist agent.” (One finds a similar corollary in today’s targeted mistreatment of Muslims who, no matter what they do, are always deemed suspect by the authorities, the media, and lots of our Facebook friends).

Indeed, because International Women’s Day was pegged by congressional investigators as a Communist holiday, those labelled as “stooges” of the Reds included IWD supporters like Eleanor Roosevelt and Helen Keller. Storrs points out that the “gender and sexual conservatism of the New Right that emerged in the 1970s” was remarkably similar to that which drove the Red Scare.

“For conservatives of the 1940s and 1950s, no less than their successors, antifeminism was an integral objective as well as a convenient tool in the struggle to turn voters against the ‘Washington femmocracy.’ Conservatives cast the civil service as a bureaucracy of short-haired women and long-haired men bent on replacing the traditional family with a ‘womb-to-tomb’ welfare state (forerunner of today’s similarly feminized spectre, the nanny state). Imperfect as they were, government measures such as public assistance and equal opportunity weakened the prerogatives not just of employers but also of men as heads of household, by reducing women’s dependence on the family wage system. Conservatives tried to weaken public confidence in government regulatory and social agencies by highlighting women’s influence in them, and by linking feminism with un-Americanism.”

While viewers of Trumbo will leave the movie theatre feeling inspired by his stand, it is important to remember the women who refused to co-operate, such as playwright Lillian Hellman, who famously declared to HUAC, “I cannot and will not cut my conscience to fit this year’s fashions.” As Alice Kessler-Harris points out in her recent study, A Difficult Woman, “Coming from a woman, this finger-pointing proved especially galling,” adding that more recent controversies surrounding Hellman’s recollections of certain events in her life generated huge criticism, anger, and incessant insulting comments about Hellman’s looks. Kessler asks whether the tempest created by the Hellman debate would be half as intense if she were not a woman, concluding: “I tend to think not. Hellman’s life as a woman contains…a crucial contradiction around the issue of freedom. Hellman sought freedom not only in the world but for herself. That search is illusory, perhaps in general but certainly for women.”

Women fight back against HUAC

Who broke the blacklist? Who ended the long career of the witch-hunting HUAC (which officially dissolved in 1975)? One might think from watching Trumbo that it was Trumbo, Kirk Douglas, and Otto Preminger, though I think Trumbo would be the first to concede that his efforts, valiant as they were, constituted one piece of a much larger struggle waged by countless individuals and groups over many years.

Certainly, one of the least heralded moments in Red Scare history, but one which scholar Eric Bentley in Thirty Years of Treason called the crucial blow in “the fall of HUAC’s Bastille,” was the miscalculated move to issue 14 subpoenas to members of the nuclear disarmament group Women Strike for Peace (WSP). WSP founding member Amy Swerdlow’s excellent history of the grassroots phenomenon notes that the group garnered 49 volumes of FBI files for, among other activities, holding educational events, picketing, and collecting baby teeth to prove that fallout from nuclear testing was winding up in their babies’ bodies.

Swerdlow dedicates a chapter to the manner in which the boys with the gavels were humiliated by WSP members’ dignity, humour, and pointed refusal to co-operate. While a decision was made to stand with anyone fingered by HUAC, WSP also refused to carry out purges of anyone who might be or could be assumed to be a Communist (unlike so many labour, peace, and civil rights organizations of the period, including the American Civil Liberties Union). Swerdlow says members of the then one-year-old organization were curious about why they had received such high-profile subpoenas, but not unaware that “WSP’s potential power to bring the ‘average’ woman out of her kitchen and into the political arena was becoming a source of concern to conservatives in the media and the surveillance establishment.”

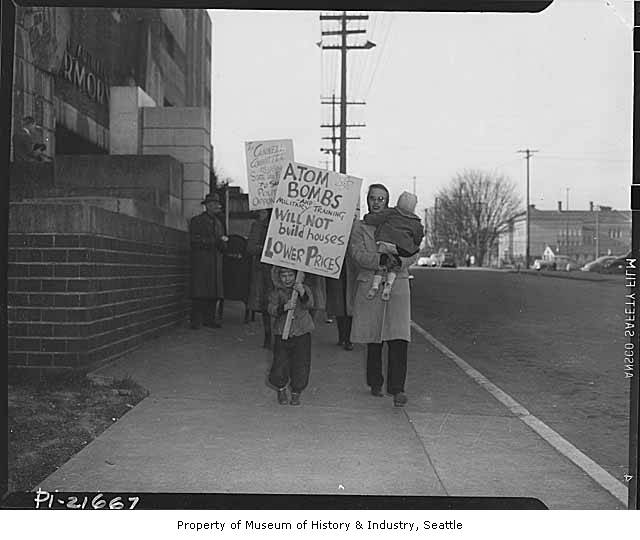

Indeed, a year earlier, over 50,000 women (self-defined “American housewives”) went on a one-day strike against nuclear weapons in over 60 communities. They “came out of their kitchens and off their jobs to demand that President Kennedy ‘End the Arms Race–Not the Human Race.'”

HUAC believed that this seemingly naïve group of peacenik moms pushing prams outside federal buildings had been infiltrated by Communists who had duped them down a dangerous path. Rather than treat the subpoenas with fear, WSP saw this as an opportunity to confront the real national security threats — nuclear terrorism and inquisition committees — and over 100 women wrote to HUAC demanding that they too be heard by the committee, though they would name no names. Swerdlow says the group’s response “was so ingenious in its exploitation of traditional domestic culture in the service of radical politics that it succeeded in doing permanent damage to the committee’s image.”

Members of the Los Angeles WSP chapter took out an ad in the LA Times that asked:

“Are they afraid the women are planning acts of sabotage, poisoning the water supply, perhaps? Hardly likely, especially from a group that first met to protest the poisoning of the earth’s atmosphere by the Soviet Union, France, Britain, and the United States. Are they afraid that the women will talk too much? Yes, very likely! They are afraid of women who are not afraid to express unpopular views.”

Come hearing day, the Congressional room was overflowing with 500 women, many with their babies in hand, as witness after witness turned the tables on HUAC. After an opening statement from HUAC’s chair, who said “peace propaganda and agitation have a disarming, mollifying, confusing, and weakening effect on those nations which are the intended victims of Communism,” WSP witnesses turned the hearings into an investigation of HUAC and a platform to discuss a movement that arose because “when they were putting their breakfast on the tables, they saw not only the Wheaties and milk, but they also saw [radioactive] strontium 90 and iodine 131…They feared for the health and life of their children.”

Speak treason fluently

When one HUAC member asked WSP member Blanche Posner, “Did you wear a colored paper daisy to identify yourself as a member of the Women Strike for Peace?”, she replied: “It sounds like such a far cry from communism it is impossible not to be amused. I still invoke the Fifth Amendment” in refusing to answer the question. Posner, Swerdlow writes, was “forceful, impertinent, and disdainful of the committee’s power and purpose. She embodied…outraged moral motherhood,” and set the tone for the remainder of the hearings. A Vancouver Sun report concluded HUAC had met its Waterloo when:

“[I]t tangled with 500 irate women. They laughed at it…. When the first woman headed to the witness table, the crowd rose silently to its feet. The irritated Chairman Clyde Doyle of California outlawed standing. They applauded the next witness and Doyle outlawed clapping. Then they took to running up to kiss the witness…Finally, each woman as she was called was met and handed a huge bouquet. By then Doyle was a beaten man. By the third day, the crowd was giving standing ovations to the heroines with impunity.”

We know that our efforts as resisters against climate catastrophe, depredation of Indigenous communities, and other social ills will continue, as they always have been, to be viewed by CSIS and the RCMP as borne of traitorous intent. During these times, it serves us well to look back on these historic examples of resistance to the inquisitions that are led by guardians of wealth, power and privilege.

“You speak treason,” King John says to Robin Hood in the 1939 movie classic.

“Fluently,” replies a grinning Robin.

So while we enjoy Trumbo and Suffragette among other movies this December, we await the story of Women Strike for Peace, among other herstories, on our screens. Now there’s a film I’d really like to see.

Matthew Behrens is a freelance writer and social justice advocate who co-ordinates the Homes not Bombs non-violent direct action network. He has worked closely with the targets of Canadian and U.S. ‘national security’ profiling for many years.

Photo: IMLS Digital Collections & Content/flickr

rabble is expanding our Parliamentary Bureau and we need your help! Support us on Patreon today!