Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

As someone who, in the past, attended a lot of NDP conventions, I was as shocked as anyone by the federal NDP’s rejection of Tom Mulcair at their convention. It’s easy to understand the frustration of NDP constituency activists. The gnawing hurt of seeing victory snatched away in last Fall’s federal election, losing dozens of respected MPs, and being relegated to third-party status again was hard to take after the heady heights of the polls as recently as last August.

Riding activists were frustrated with a federal campaign that failed to roll out the kind of progressive platform planks needed to convince swing voters. Far worse, the party’s play-it-safe frontrunner strategy, with the pledge of no deficit, left the party vulnerable to being outflanked on the left by Trudeau and Liberals. When things started going south after the niqab disaster in Quebec, all the campaign’s problems were brought into high relief.

Mulcair did the honorable thing and accepted responsibility for the disastrous showing. He was the only one of the whole team to do so despite being only one of the architects of the campaign. In many ways, he was a puppet controlled by a small team of NDP elite. Together, they made bad decisions on such issues as deficit financing and the play-it-safe strategy. That team included many of the personalities involved in other recent NDP debacles, like British Columbia in 2014, which was no less shocking a loss than the federal one in 2015. In B.C., the party managed to seize defeat from the jaws of victory with another play-it-safe, feel-good frontrunner campaign patterned on a misunderstanding of what made things work so well for Jack Layton in 2011. That misunderstanding was then applied to the federal campaign in 2015 with similar results.

Party rules around confidentiality and solidarity mean that no one will ever know who advocated for the zero-deficit or play-it-safe tactics or who wanted to make sure that no one could ever refer to Mulcair as Angry Tom again. No one will ever say who put the leader in a bubble for the federal election campaign, but it’s quite likely that it wasn’t the leader’s choice. Anyone who has seen Mulcair in action up close knows that he is strong-minded but also personable, a quick wit, thoughtful, and progressive by instinct.

Almost immediately upon becoming leader of the NDP, however, his style changed dramatically. Instead of the well-informed give and take he formerly demonstrated with reporters, Mulcair moved suddenly to a far more scripted style. Was this his choice, or something his management group called for? It’s unlikely the public will ever know.

The public does know that his predecessor Layton was also very nervous about proposing tax increases or deficit. So the party’s purported move to the centre hardly begin with Mulcair. It’s much more likely that a consensus of opinion developed among the party’s elite to the effect that the NDP should not propose new taxes or deficit spending lest it be seen as not credible on economic issues. Mulcair certainly did not originate this kind of thinking. So while it was satisfying to many of the delegates to give him his walking papers, they may very well have been firing the wrong person. Only one person was fired when the whole team was responsible.

Now the party faces real challenges. It has to finance leadership campaigns and a leadership convention, and then once a new leader is selected, it will have the same problem is it had with Mulcair getting a new leader recognized publicly, when the opposition leader Trudeau is so well known because of his family name. The new leader will not have the benefit that Mulcair would have had of having been through an unsuccessful federal election campaign, and everyone knows that you learn more from defeat than from victory.

So instead of having the battle-hardened and finally-recognized-by-the-public Mulcair, the NDP will have someone new who they have to introduce and sell to the public as a worthwhile option to Trudeau. The new NDP leader will have the baggage of the Leap Manifesto, which will be seen as anti-Western as well as the baggage of having fired its first Quebec leader on trumped-up charges.

After all, Mulcair, though cautious and lawyerly, made no major mistakes as NDP leader.

It was satisfying to see convention delegates reject what those at the centre of the party obviously wanted them to do. Federal NDP conventions can be offputting, with the whole agenda rigged to support the objectives of the Centre, squelch embarrassing debate, and keep troublemakers out of positions of influence. So it was richly satisfying to see the Centre rebuked as harshly as it was on Sunday. Whether it was a smart play remains to be seen. Whether Mulcair is truly what the Centre wanted is also open to question.

Maybe, as some friends have argued, Mulcair did need to go. Indeed he’s a grandfather, and will be older next time. He certainly is not fiery or charismatic in the usual sense, but he has indeed been a highly effective opposition leader and, as Peter Julian said on CPAC after the convention ended, he had a lot to do with Stephen Harper being exposed and rejected by the Canadian public.

Maybe it will prove to be good marketing to send him out to pasture, and bring in someone new and sexy, but there are real costs, and the real risk of losing the stronghold in Quebec that Mulcair was so instrumental in creating for the NDP.

Ish Theilheimer lives in Golden Lake, ON, where he has been an NDP activist for 30 years.

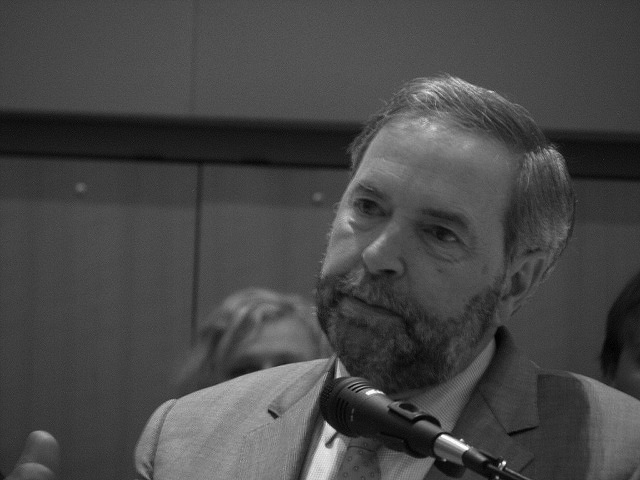

Photo: flickr/Laurel L. Russwurm